The way to tell the story, it seems to me now, is to start with the death. That might be the seed it sprang from, the thing that made me want to tell it in the first place.

First you must picture the old Stock Exchange, a grand building on LaSalle, Chicago’s Wall Street, surrounded by the old-line investment firms and brokerages, the banks that control most of the city’s money. Even on this block of opulent old buildings, the entrance of the Stock Exchange stands out, as compelling as an invitation from a stranger. The arch is thirty feet high and forty wide, bursting with geometric patterns that are at once floral and abstract. On each side of the arch, a row of narrower two-story arches that define and light the Trading Room – the heart of the building – and above these, an undulating façade, level wall then jutting bay, a rhythm as organic as the rise and fall of waves on the beach a few blocks east. The design is early Chicago School: form follows function, ornament grows from purpose. The steel frame skeleton is not hidden, but exposed in the grid of vertical piers and horizontal spandrels. Like a classical column, the building has a distinct base, shaft, and cap.

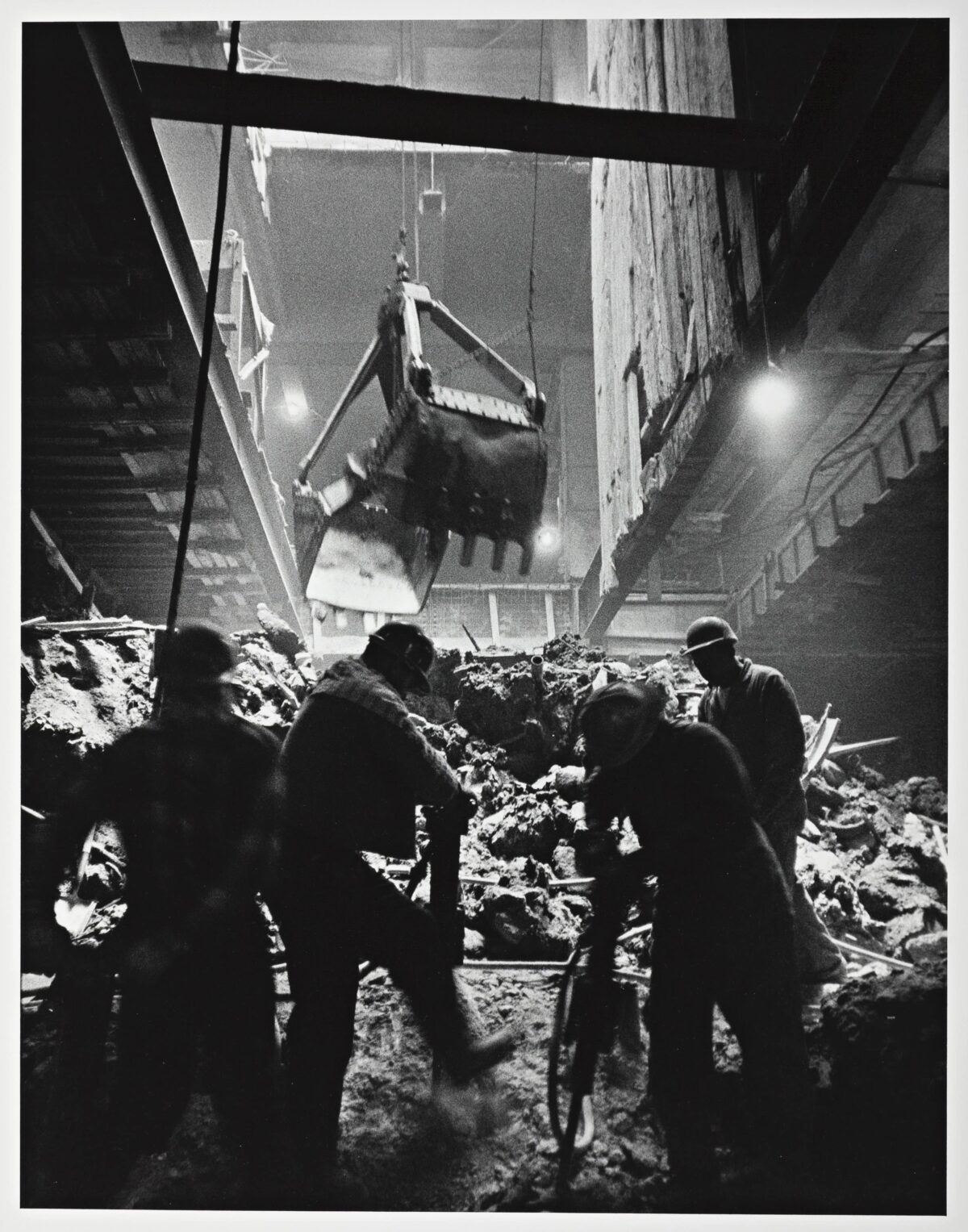

On this day, however, the music stops abruptly above the sixth floor – no ornate cornice, no colonnade to cap the structure. Instead, naked beams reach into the sky like exposed bones, their terra cotta flesh peeled away. After six months of demolition, the building looks like a work in progress or something newly bombed, the fresh casualty of a city at war.

An unlikely thief is prowling the second floor. He wears a dark jacket over army fatigues and carries a small black bag containing chisels, hammers, screwdrivers, penetrating oil. In his other hand, most likely, a long pry bar and a handwritten list, which I have copied in my notes: 2nd Fl. – stringer, dec. lintel, elev. grill (another fragment is scrawled at the bottom, but I can’t make out my own writing). Despite the tools and his six-foot frame, his military dress, he is not threatening. He wears thick horn-rimmed glasses and has a dimpled baby face. He is a man who, even in smiling photos, projects the lonely, ineffectual air of a scholar or monk.

It would be thin and mottled, the fading light, filtered through broken walls and obscured windows, like the patchy sunlight that makes it to the floor of a thick forest. Chalky dust, unsettled by the day’s destruction, floats in the air like fog.

A Death

He is comfortable navigating wrecking sites but moves cautiously tonight; even he rarely goes into structures this compromised. Perhaps he also is savoring the moment, knowing this is the last time he will be inside yet another of the Master’s great works, knowing there is something final, almost ceremonial about his mission tonight. He steps through a doorway and finds his path blocked by a pile of rubble. He works his way around it, balancing precariously on a kind of cliff, an unmanageable mountain of material on his left and a void on his right – a two-story drop through a hole in the floor. Is he using a flashlight? Maybe, or at dusk, perhaps enough natural light penetrates the building’s shell for him to see. It would be thin and mottled, the fading light, filtered through broken walls and obscured windows, like the patchy sunlight that makes it to the floor of a thick forest. Chalky dust, unsettled by the day’s destruction, floats in the air like fog. The wreckers spray water to damp the dust down and drill holes in the floors so it can drain. It drips tortuously through the remaining floors now, its patter echoing in empty rooms, as if a light rain is falling inside the building. He must feel a little like he is walking through woods in autumn, the fog and rain, bare columns exposed like defoliated trees, a dense undergrowth of broken bricks and concrete, wood and wiring at his feet. Even in death the building seems alive to him, the way a forest is alive in fall, an impression he knows would please Louis Sullivan, its architect.

He thinks of dinner. Even if everything goes well (it never does) and the stuff he came for is easily removed, by the time he loads it into his car, drives home, unloads, showers, and picks up Lucy, his fiancé, they will be late. There is no question of that – his parents will expect it – but how late? They won’t even check their watches for half an hour, knowing Bud and guessing what he’s up to. He thinks he can make the seven o’clock dinner by seven forty-five, eight at the latest. His brother and sister-in-law are probably at his parents’ already, helping to prepare the meal, poking fun at the latest, unexpected turn in his odd life. He kicks a wooden plank out of his way and it skitters across the floor, echoing in the hollow space. How does he feel? Impatient and sad, I imagine, nervous if not overwhelmed, and maybe something like euphoric, all at once. There would be, as always, the excitement of salvaging, the thrill of getting to another piece of Sullivan before the wreckers, as well as the deadening grief of a demolition in progress. But tonight, the dinner adds something else. He is no doubt annoyed that he must rush his last trip through the old Stock Exchange and just below the annoyance must be joy at such a luxury. Lucy is expecting him, waiting for him, and so he can’t waste time. He has somewhere to be. He, Anastazy “Bud” Million, lost cause and confirmed bachelor, aesthete and odd bird, is expected. At forty-three years of age and for the first time in his life, he has fallen in love.

It is likely that passing through the great Trading Room he stops for a moment before beginning to work. He and the others spent months stripping this room – legally, for a change – and saved the entire thing. He worked feverishly with his camera, photographing every inch, every column and panel and piece of stained glass, so that whoever tried to put it all back together would get the details right. They numbered every piece, but without his eye and the exhaustive record of his photos, the room would be too complex to reassemble. When he was done photographing, he joined the others, unscrewing sconces, peeling stenciled canvas, cutting through metal lathe to remove whole sections of wall. Bud, who has made an unpaid career of saving pieces of Louis Sullivan – photographing his buildings while they stand, stealing ornament as they’re demolished – rescued a complete room (though it is only now being reconstructed). “The fragments keep getting bigger,” he joked to a friend. “Maybe one day we’ll save a whole building.”

The absence of Sullivan’s lush ornament in the Trading Room might seem tragic to Bud – of course it does, and I’m tempted to dwell on that loss – but I know that he also considers the denuded space beautiful in its own way, a rare opportunity. When the room was cleaned and then photographed, Bud marveled to see Louis Sullivan’s polished achievement. But as it was picked apart, he saw something perhaps equally thrilling: how the room and by extension, the building, were put together, the logic and beauty of their construction. With the detailed stenciling and plaster stripped, Bud could appreciate the muscularity of the bare beams, the precise way each of the two trusses held its twelve-hundred tons, an incredible feat for 1894. Looking behind the columns’ faux marble, he understood for the first time why Sullivan had made them so prominent – not as icing, but to highlight the fact that four of them, only four, supported all ten of the building’s upper stories. He highlighted the structural elements, showing off the building’s brute strength to reflect the power of the Trading Room, a place where fortunes were made and life-changing deals done every day.

Like archaeologists Bud and the others dug, and as layer after layer came away, he must have felt that what he gained was a glimpse into Sullivan’s soul, the artist mirrored in the anatomy of his art. “Wonderful,” Bud wrote in a letter a friend of his copied for me, to experience the bones, veins, and sinews of a building, to be inside a work of art in dissection.”

Bud is a dreamer – not in the least practical – and still dreaming in the Trading Room when finally he checks his watch, perhaps feels a moment of panic, and gets to work. Dinner. He starts with the elevator grill, an exquisite piece that he is amazed has not been taken. The art-nouveau bronze T-plate is as intricate as a jeweled medieval cross, and the grill itself is covered in small spheres modeled on seed pods – in Sullivan’s essays, the “seed germ” was the favorite metaphor. The pieces Bud prefers are as functional as they are ornamental. He has been watching this one for months, but there was so much to do, so many fragments to weigh and consider, he never took it. It pains him, deciding what to save and what to leave, the constraints of space and time. One end of the grill has been knocked loose, but it does not look damaged. He oils the bolts, then ties a rope around the piece while the solution works in (he must have a rope with him also – that would be in the bag with his tools – and a wrench, he must have that, too).

He tests the first bolt and is pleased to crack it right away. Every part of a building in this state is loose – screws, bolts, nails, even the mortar holding the bricks together, which has frozen and thawed throughout the winter as wreckers sprayed water to damp the dust. He frees one bolt and then the next, and in ten or fifteen minutes, is ready to remove the piece. He pulls but the grill does not move, wedged into place for so many years, it and the building are almost inseparable. Expertly, he coaxes it from one end to the other with the pry bar and nudges the piece that he wants free. I imagine he makes a kind of noose with the rope then, looping it around the grill, to carry most of the awkward weight on his shoulders. For some reason, he does not take it to the window, where he can lower it to the alley. Instead he leaves it in the center of the Trading Room floor, as if, like so much here over the years, it is to be exchanged for another commodity. Maybe he wants to amass everything in this central spot before carting it to the other side. He drops the piece with a clang and smiles, feeling it safely in his possession.

He rests, but just for a minute. If that piece came away easily (I’m only guessing it did), it is unlikely that the next one will, and already, he is later than he thought. Maybe he feels a flash of anger during his too short rest, his earlier fight with Lucy flaring up. This dinner, planned by his parents to introduce his brother and sister-in-law to Bud’s fiancé, has ruined his concentration and distracted him from his work. Lucy appreciates what he does more than most, but not even she would have supported tonight’s quest, not on a night this important, in a structure this corrupted.

Before the fight, Bud told her only that he had “work” to do. She begged him to take the day off, or at least to end it early. If it wasn’t for Lucy and this dinner, he might salvage twice as much ornament tonight. The thought strikes him, and then he must quickly see its perversity. If there is to be an accommodation, shouldn’t it be his work that suffers, this collecting of fragments and photos, and not the life he has sacrificed for twenty years? Bud’s resentment shifts now toward the building that has kept him from dinner, perhaps even toward its architect, Louis Sullivan himself.

While other men his age have been out making money, building families and full lives, Bud has been straining his eyes in the darkroom finessing prints, scrounging in dim, dangerous buildings, saving and numbering fragments until too exhausted for anything else.

A DEAth

How does someone obsess so much over a dead artist, a man he has never met, that he can at times resent him or his inanimate creations? Maybe it’s not so odd, considering Bud’s strange life. Just think, he has spent nearly twenty years crusading to save these buildings in a city hungry to tear them down. The mayor wants shiny new structures, and these old hulks are in the way. In Chicago, that’s a simple equation. Bud fights the teardowns anyway, and as each effort fails, he photographs the doomed buildings, trying to capture their essence. An obsessive, he shoots them at every time of day, from every angle, in all seasons, never satisfied that he has done them justice. When the demolition orders come, he photographs the scaffolding as it creeps like lichen up the façade. He captures the first crash of the wrecking ball, records the accumulation of rubble, traces the buildings’ slow demise. He has devoted much of his life to documenting untimely death. While other men his age have been out making money, building families and full lives, Bud has been straining his eyes in the darkroom finessing prints, scrounging in dim, dangerous buildings, saving and numbering fragments until too exhausted for anything else. The man is in his forties and lives with his parents.

Now, when he should be home eating dinner with his fiancé and family, here he is again, alone and dusty in the dark of a condemned shell, laboring thanklessly and without pay to preserve fragments in a cause that he knows each time he undertakes it is doomed to fail.

The wrecker who finds his body is clearing bricks from the subbasement with a scoop when he sees what looks like an arm reaching through the debris. He kicks away some detritus and discovers what might be an elbow or a knee – he can’t be sure of the limb, but some piece of a man – showing through the rubble. Bud has been missing more than three weeks. He was obsessed with the Stock Exchange, and his friends told the authorities that he might have come here. The search was called off after six days, though, because officials said it was becoming dangerous for the searchers. Privately, they also said they could not hold up progress for some crackpot who was probably out of town hunting old buildings, as he was known to do, or suffering from a case of pre-wedding jitters. As they resumed work, laborers were told to be careful moving material, to look out for traces of the missing man. They did, at first, but it is only weeks after the search has officially ended, when they no longer wonder where he might be, that a worker stumbles onto a body under all that rubble.

A police forensics expert stands by as a team of firemen dig around him. The process takes hours because new rubble keeps spilling into the pit as they scoop material out. In their morbid line of work, the forensics expert and his colleagues refer to a body this old as a “soup job.” The corpse at that point has become bloated and may have burst from a buildup of gasses. Decomposition is advanced and the flesh putrefied, often beyond recognition.

As they clear the last of the debris from Bud’s body, however, something is wrong, the technician thinks. What is it? What’s missing? Then it occurs to him. There is no odor. None at all. Bracing themselves, the firemen heave the body out of its pit and onto level ground. The forensics expert leans in for a closer look. If he had to guess, he would say the man had been dead a day, if that. Except for the fine layer of white grit that covers his skin, he looks healthy, almost alive.

Beneath the rubble, the body has been tightly packed in plaster, loose concrete and cold water, a mixture that has preserved it perfectly. The stiff white figure looks like a piece of the building, a statue made from the same materials workers have hauled away by the ton. There is something lovely about it, so rigid and pale, gleaming like marble in the early morning light.