Powering through a cerulean sky, haloed in a faint whitish glow, “Woman Flying” (1999), one of the earliest works in Katherine Bradford’s first major museum survey (Portland Museum of Art, Maine, through September), has the effect of clear but muted fanfare. The airborne subject’s arms are spread, her face featureless, her body husky and just a little awkward. Attached to her shoulders is a bright red, Superman-style cape. The image is of slightly self-deprecating valor—a middle-aged woman, perhaps, gifted with flight, game for adventure, and eager to do good. Bradford was fifty-seven when she painted it, and she had been exhibiting for roughly a decade. Her work henceforth, “Woman Flying” suggests, would picture risk, joy, loneliness, compassion, and exposure. There would be diffidence, and a healthy sense of possibility. There would also be a sense of humor. It would be rueful.

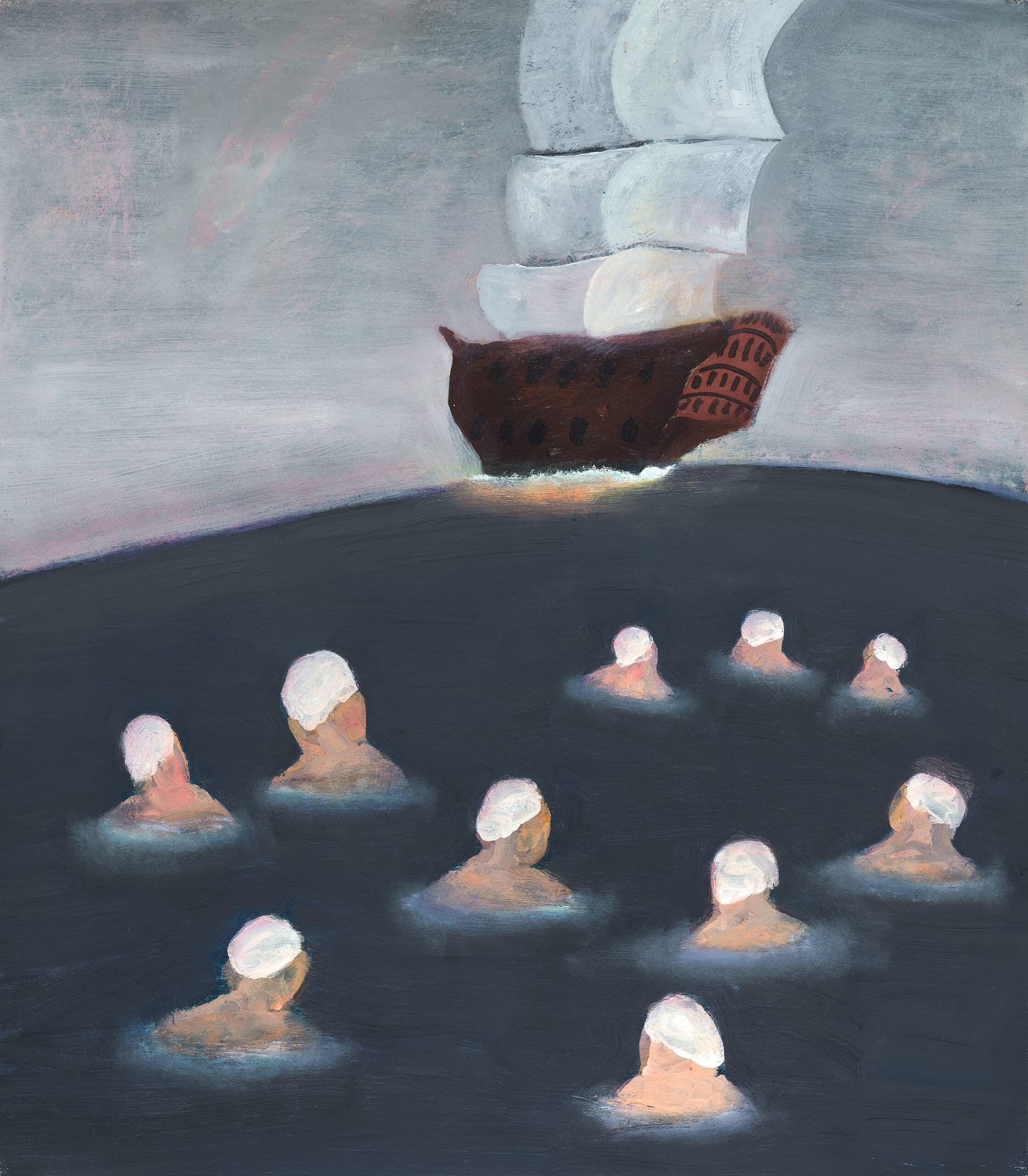

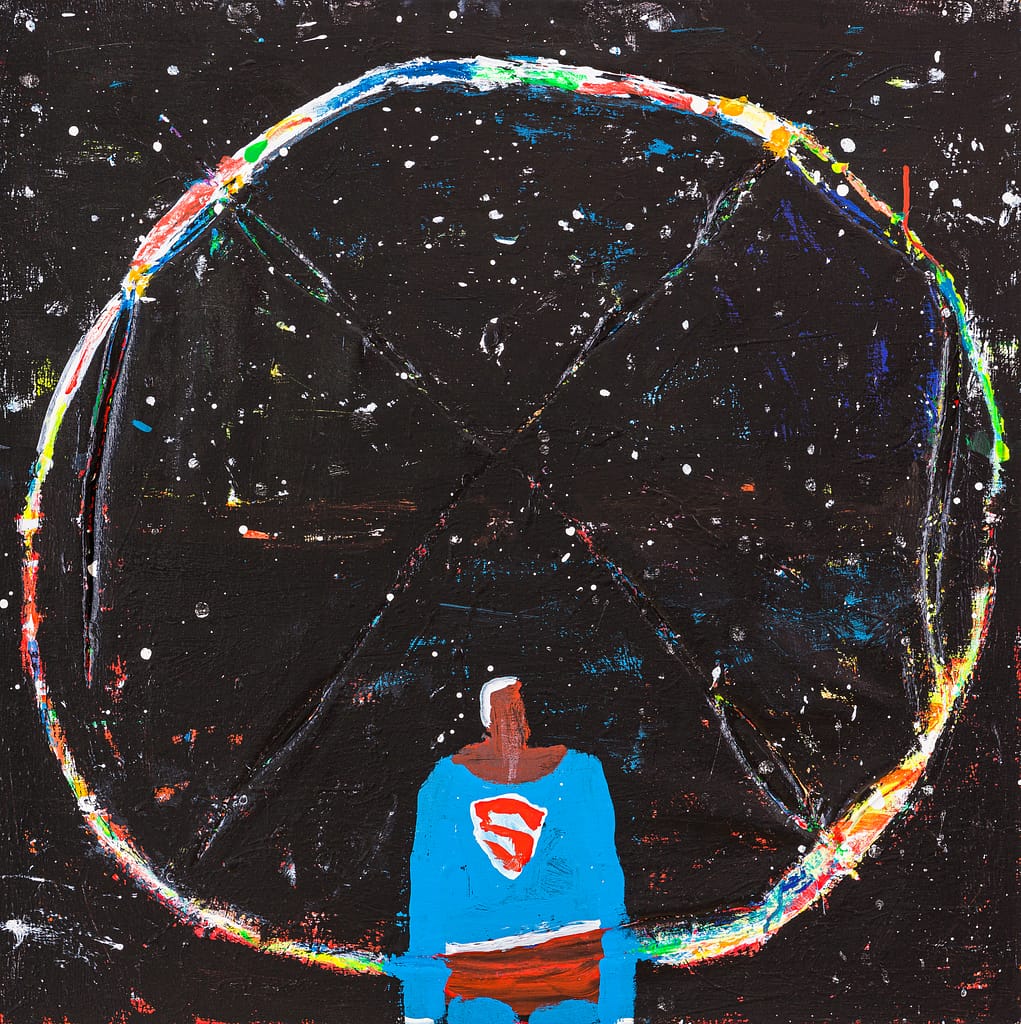

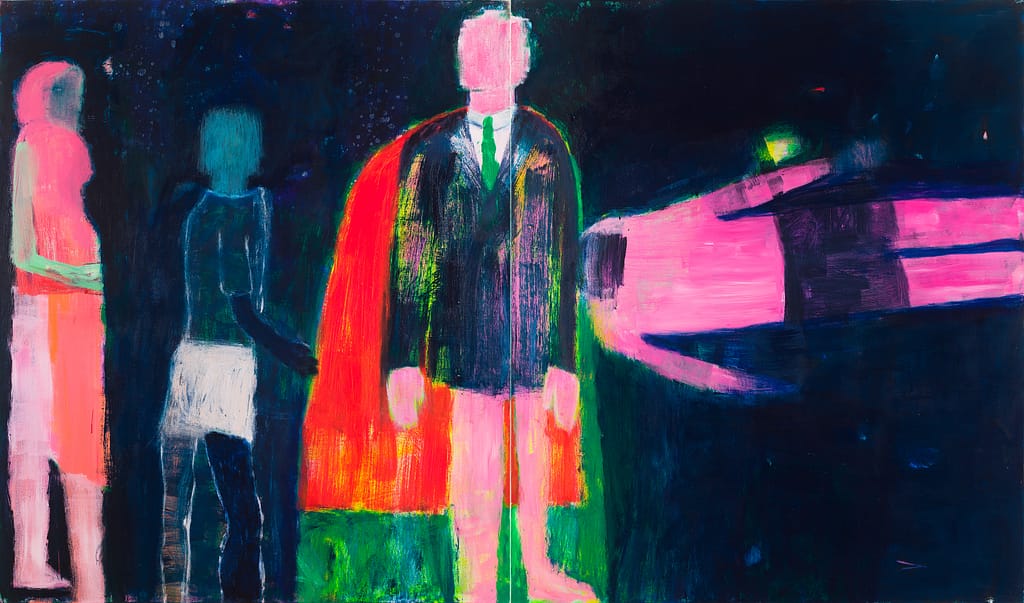

Among other early solo venturers is “Woman in Water”(1999), in which the subject is up to her armpits in seawater a chilly shade of blue. She seems to be standing on tiptoe, not ready to give way to the waves; one outstretched arm grabs hold of the painting’s edge as if for balance. Her naked body is rosy with determination. Among further heroic singletons are “Super Flyer” and “Superman Responds, Night” (both 2013), “Superman Big Circle of the Universe” (2015), and “Superman Shelf Painting” which, as the title suggests, has a sculptural component. Gently humorous, they all depict superpeople adrift—lost in an inky cosmos, or spiraling away to invisibility, or diving into velvety night skies. Most are, ironically, fairly small. The heart is willing, they seem to say, but the flesh shrinks. These brave but diminutive soloists have been replaced, in Bradford’s more recent paintings, by close-knit families related by blood, friendship, and art, and the figures have grown substantial, even monumental. One new group portrait shows four robust “Superheroes” (2020), arms proudly linked. Bradford’s heroes, both the hesitant early ones and their more confident successors, have relations with Dara Birnbaum’s 1979 video of Lynda Carter spinning madly, over and over, from civilian clothes into the spangled bra-and-panties costume of TV’s Wonder Woman, and kinship, too, with Pope.L’s abject, real-life crawl down the length of Manhattan, a Superman cloak on his prostrated Black back.

Superman Responds, Night Superflyer Superman Big Circle of the Universe Woman Flying Woman in Water Group Swim Two Tables Fear of Waves Dark Ship Prom Swim Green Motherhood Superheroes Green Tie Fear of Shoes Pond Swimmers, 2016

The 2010s were of figures swimming in water, air, or a liminal zone between or beyond that is peaceful, confounding, and multivalent; occasionally, such images appear in current work. In a 2017 interview, Bradford said, “I think that I’m attracted to the sky, the ocean, and outer space, because you tip in all of those directions pretty easily. You can slide from the ocean right into outer space. There aren’t divisions.” And, she added, “Water and sky are forgiving things to paint.”

Bradford is careful with metaphors, and as with kinds of space, she is partial to those that can tip. To be at sea is an adventure, but also a state of uncertainty. Hold on, she seems to say, the planet is spinning and it is very wet; it’s a wonder that the seas don’t all just slosh off into infinity. Most of the world is water, as are most of our bodies. Mystery lurks: the deepest parts of the ocean are only now being explored, and they conceal life we’ve never seen—life not meant for vision, because it is really dark down there, as dark as outer space.

At the same time, water and outer space alike offer buoyancy, which has its own range of reference. If gravity was a leading physical concern of the Minimalists who dominated the art world when Bradford was in school, making work—exemplified, for instance, by Richard Serra’s prop pieces—that relies for its meaning on an equivalence between weightiness and seriousness, Bradford’s imagery is its antimatter. Hers is a world aloft, afloat. And as she suggested by calling sea and sky “forgiving” subjects, the medium her figures are variously suspended and submerged in is neither water nor air, exactly, but paint—that is, they are suspended in imagination. As she has put it, matter-of-factly, “I think of water equaling paint.”

Toggling between formal and figural concerns is what she does in the studio every day. In the early paintings, the floating figures are smallish and busy paddling, diving, and surfing in oceans and ponds, or taking their leisure in swimming pools or bathtubs; some of these bodies of water themselves float in space. In “Night Bath” (2003) a female body, stretched out comfortably in the water, is seen from above, in satellite view; the tub in which she floats is itself adrift in a night sky. Nakedly human—though her face is modestly downcast—but also celestial, she seems to be entering the range of a passing sun, which casts a warm glow on her shoulders and head, leaving the rest of her body in bluish shadow. “Fathers” (2013) is a later nocturne in which a group of guys, red as lobsters, lounge convivially around the perimeter of what could be a giant inflatable pool, gallantly sailing through interstellar space. These fathers are dwarfed by the cosmic vastness; many of Bradford’s swimmers are even smaller. No more (nor less) than ciphers, they are markers for humans that form a kind of alphabet of gesture and presence, but also, as ciphers, a secret code, meant for privacy. λ

Excerpted from Flying Woman: The Paintings of Katherine Bradford, published by Rizzoli Electa. Purchase a copy of the book here.