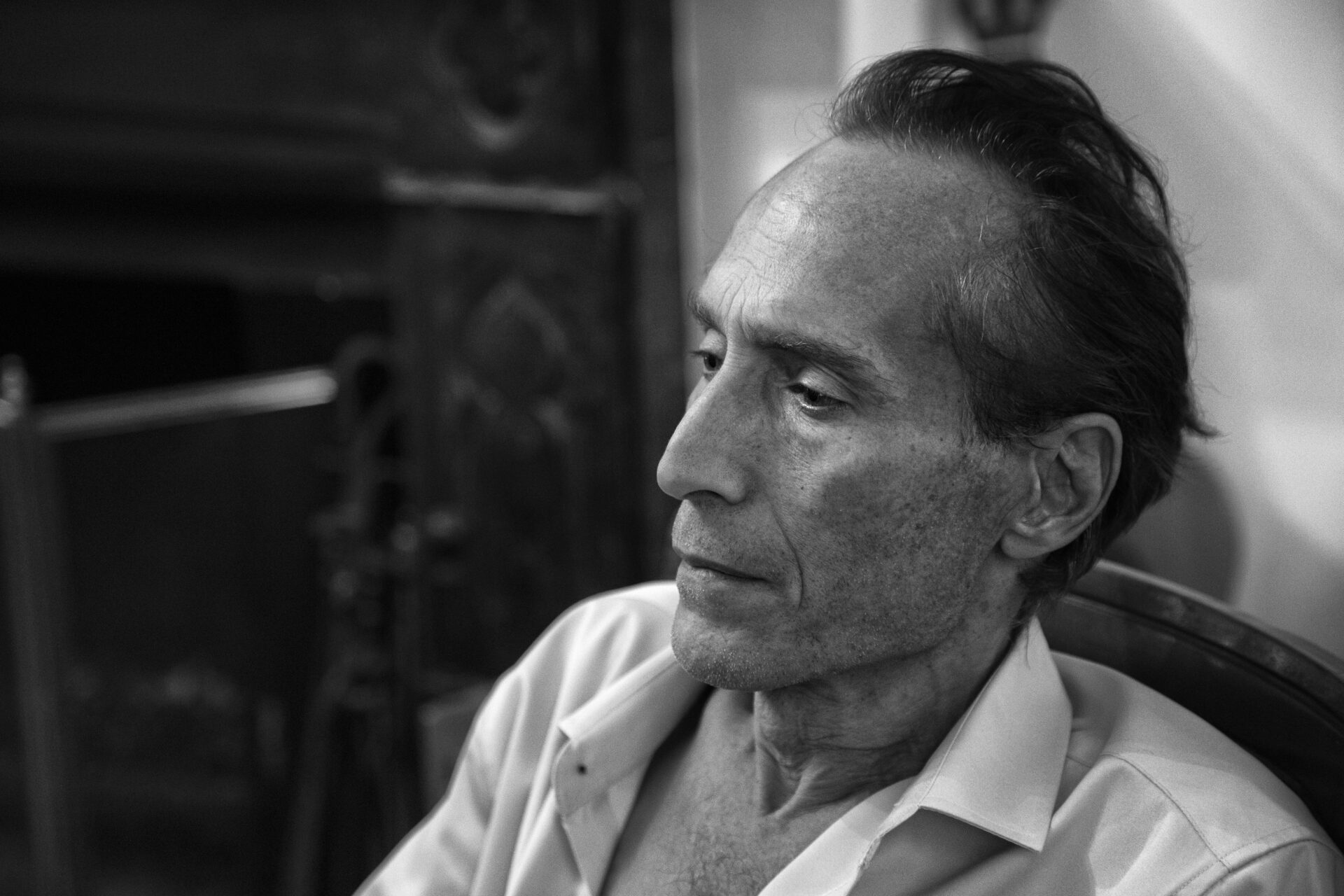

I’m on the couch with Beckett Rosset watching a Giants game. He’s gifted me, like the thousands of guests he’s had in his home this year, the pleasure of chain smoking indoors. This afternoon, Beckett is getting ready for a reading he’ll perform in a few hours at Andy Maillet’s Room 2 salon series. He also has to rehearse for his acting debut in Guerilla Days, a one act-play by Roman D’Ambrosio, part of the Cars & Women issue launch party. Beckett will host both events in his home, sometimes known as Bar 69, usually just “Beckett’s.” A slew of chic periodicals litters the apartment floor: Mars Review of Books, Dirty Magazine, Heavy Traffic. Despite — or perhaps because of — his heritage and namesake (he is a son of Grove Press’s Barney Rosset, Samuel Beckett’s American publisher), the last thing on Beckett’s mind are the old legacy names of New York publishing. More than almost anyone in the city, he’s at the center of the explosion of energy underway in downtown magazine and theatrical culture. He has founded a new reading series, Tense, hosting writers like Christian Lorentzen, David Yaffe, and Matilda Burke. This year, playwrights Matthew Gasda and Cassidy Grady have staged numerous new works in his living room. Beckett is Dimes Square’s Joe Cino.

Once we’ve read through Guerilla Days, we move on to his own piece, which he’ll perform later tonight. “To this day, I get a Pavlovian nausea when I pass by the Providence hotel”: Beckett’s essay depicts a Bowery flophouse where even the roaches are hooked on crack. Addiction, homelessness, Riker’s Island: nearly all the writing he’s let me read revisits the depths he sank to in his street years, which began after his expulsion from Rumsey Hall Boarding School at the age of 13.

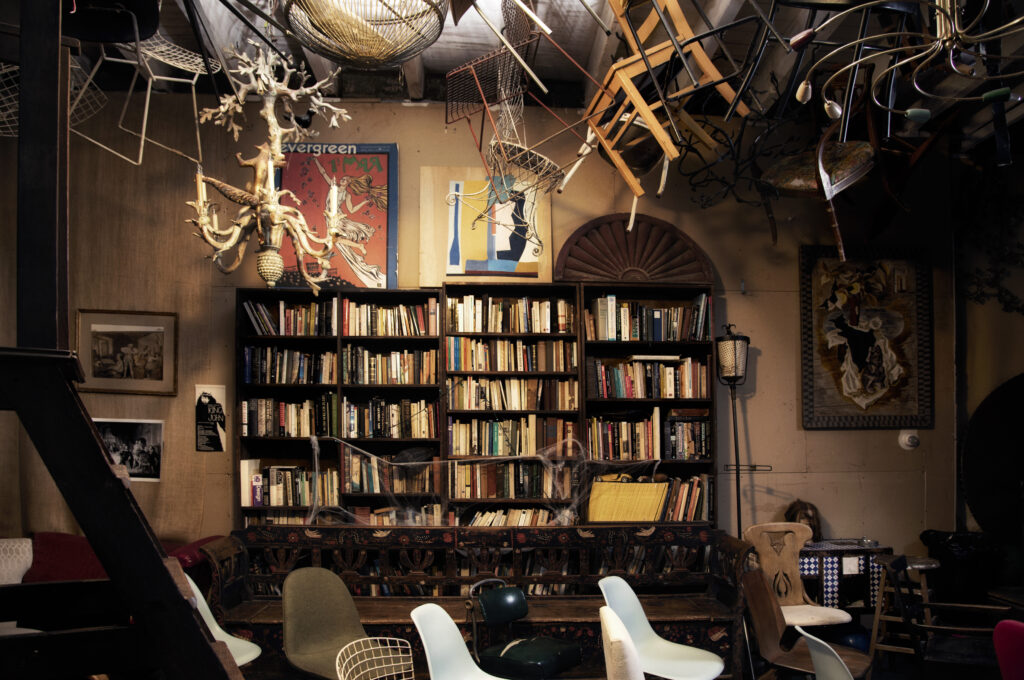

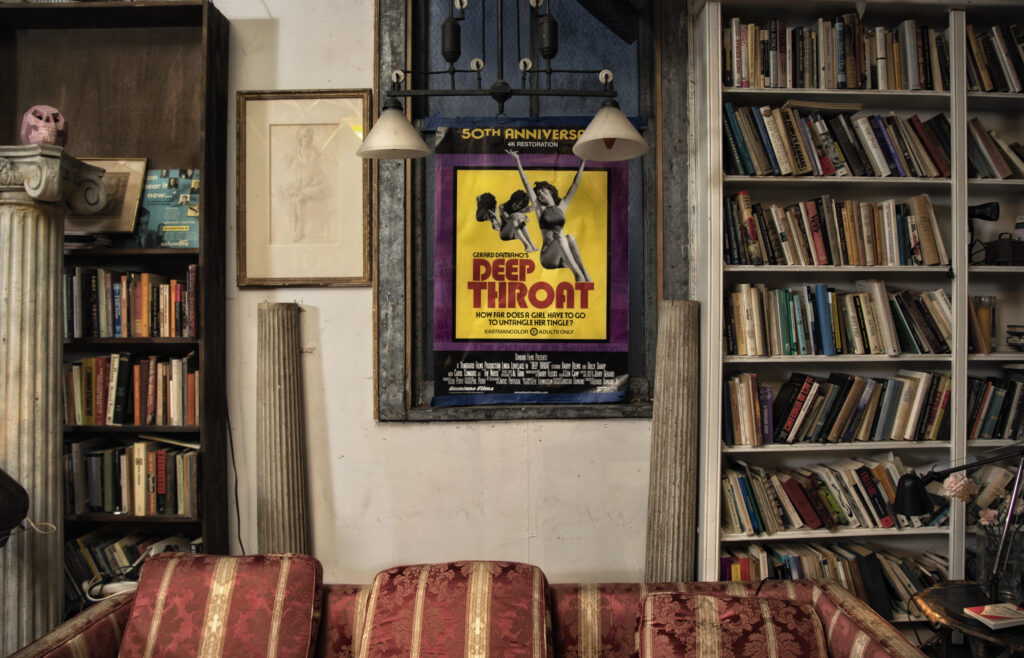

Besides the incredible antique furniture, library, and sheer square footage of Beckett’s venue, there has always been something else: it’s all temporary. For the past year, Beckett has lived with the pressure that he may have to leave the house, his home for two decades, or at a minimum, stop hosting events. The plays, readings, launch parties, and screenings kept happening, but no one knew if it would all even exist in another month. During the photoshoot for this magazine, Beckett received a phone call informing him that the house would go up for auction at the end of November. A few weeks later, following an estate sale, he hosted his final party on the 28th of November.

Beckett is at ease talking to anyone, one of those people who is exactly the same whether he’s with a barista or a New York Times columnist scoping out his scene. He is uncomfortable, however, speaking about himself. This edited conversation doesn’t include the dozen or so times Beckett stopped to ask why anyone would want to hear about him or his life. Over the course of a few weeks, we met twice for formal interviews, about three hours of tape total, and numerous times in between we exchanged writing, picked up flowers at Trader Joe’s, and smoked inside some more.

— Ben Shields

Photo by MIchael Sharkey

Shields: If I may quote you, here is one of my favorite passages I’ve seen of your writing, from your essay in progress, “Wandering Violence Thermometer”: “The funny thing is I have barely written throughout my life… but I think I have been writing in a way, all this time. Except it is not in the form of the written word. It is the endless dialogue in my head that I have been constantly editing and refining and stylistically altering to suit my moods my needs my ego…it never ceases unless I sleep and even then I’d imagine it’s going on subconsciously. And the second I awake it begins anew. I guess some would simply call that consciousness but for me, it is in written form, a floating line of words wending through my cranium, a silent verbal film flowing through the software of a brain that is ceaselessly mercilessly editing and pruning and altering and emending, endlessly seeking out a better way a better solution than just running away and giving up and dying…” Why do you think that this year your writing has moved from the internal to the external?

Rosset: I think the fact that I’m surrounded by people like you. I’m surrounded by people who are writing, who are creating art, and it’s been inspiring enough. You know, like I said to you once before, I don’t seem to have any control over when I can write. It’s like a spigot that gets turned on.

Shields: What are you working on now?

Rosset: The next thing I’m theoretically reading [at TENSE Reading Series]. I’m nervous as fuck about it. It’s called “Der Letzte Waltzer.” My friend Shoshi Rosen, who I know through Matt Gasda, is editing it. It’s just incredibly personal and it’s incredibly contemporary. It’s not something I wrote 20 years ago. What’s making me nervous is reading it out loud. I’m afraid I’ll start crying. It’s about an intensely personal thing, somebody I loved. And about dancing.

Shields: So this is new. But many things you’ve sent me you say are from years ago. What’s it like going through an archive like that?

Rosset: Sometimes it’s uncomfortable. Sometimes it’s embarrassing. Sometimes it’s amusing. It depends on my mood.

Shields: You’ve written about the effect of your namesake, Samuel Beckett, on your own work, and said that the novel Murphy was the book that made you realize you had to write. What about that novel moved you above all others?

Rosset: There’s a scene where the two guys are playing chess and one realizes that the other is just basically trying to commit suicide. They’re in a mental institution. I’d never read anything else like it. Now, as a teenager, I read everything of Beckett. [In 2001] I was sitting all alone in an SRO single occupancy room in a crack house in the Bronx infested with roaches. Court ordered to live there because I was in an outpatient drug program and they made me live in the borough where the program was…I found Murphy on the street. That was my trigger. So I started reading that and then I found a pad and a pen, and I just started writing furiously about being in Riker’s Island.

Shields: I read the account in your dad’s book this morning of your photoshoot with Beckett and Richard Avedon when you were a kid.

Rosset: Really? Huh. Shit like that never occurs to me. Avedon had reached out to my dad and said, “I want to photograph Beckett. Can you make it happen?” Beckett probably ignored him when he approached him directly. Avedon wouldn’t shut up. Beckett didn’t say a word. Beckett did not like him. I could tell that. He smiled and put his arm around me. He liked me, he liked my dad, but he didn’t talk. My dad gave him a bottle of Irish whiskey, then Avedon gave him a photograph and he left it on the table. He clearly hated Avedon and he didn’t like being photographed, period. That’s how I got involved. Beckett suggested it and said he wouldn’t do it unless I was there.

Shields: Did you ever meet him again?

Rosset: No. But he sent me postcards. “Dear homonym.” I don’t have them now. My dad sold everything in his archive to Columbia.

Photo by MIchael Sharkey

Photo by MIchael Sharkey

Shields: You have founded a new reading series, TENSE, and I know you intend one day to start a magazine of the same name. What is your vision for it?

Rosset: Politics, sex, art. A little bit of both art history and contemporary reviews. What I grew up with on the walls were posters of Miró, Toulouse-Lautrec, and believe it or not, Henry Miller watercolors… I just thought of Joan [Mitchell], my dad’s first wife. Because that was my art experience. When I was 19 or 20, I ended up in Paris before I flew back to New York. I met her in a restaurant somewhere. I got there first and then she, I mean, I’ll never forget it — she came in, the whole restaurant stopped. I didn’t understand how big a deal she was. The waiters stopped serving people, all came scurrying over. There was a bottle of Montrachet popped open, and I remember it was like, a good bottle of Montrachet. My friend Charlie’s parents were in the wine business, so I had been learning about wine. I was like, yo, that’s a $200 bottle. Eight bottles later, something insane, she’s screaming at me in the restaurant in public, with everybody listening. You’re gonna go back to New York and become a fucking junkie. You’re gonna go to prison and you’re gonna become a heroin addict and you’re gonna be a homeless loser. Later we were playing billiards. She was trying to explain color to me. She drank me under the table, she just had so much presence.

Shields: I’m amazed that you were able to even focus on a color lecture after what she said to you.

Rosset: I at least had enough sense to know that I was being given a gift. Then the next day she gave me a check for $5000 and sent me on my way.

Shields: Now, back to Riker’s Island. You’re working on writing about your time there. How many times did you go?

Rosset: Nine. Almost all for shoplifting. Sometimes for possession, but really shoplifting. My longest stay was nine months. I’ll show you my rap sheet. The most powerful story I could tell you is the first time when I finally got to the island. You go into these holding pens, bullpens, they call them, You go from one to the next, they’re processing you, or whatever. But when you’re an un-sentenced inmate, it’s different. So you go to a building they call C 95 and you’re still wearing your street clothes. But they need to, like, cleanse you. They make you strip. So finally you get into this bullpen where you then take a shower. Just this weird little showerhead, I swear to God dripping ice-cold water. There’s mold and fungus. It was disgusting. And you’re dope sick. You gotta get naked and stand under this thing, which isn’t cleaning you. Then you put your filthy shit back on. And then I remember coming out [into an] inner corridor, then it stops and there’s another corridor going the other direction. And just right in front of me is the Dostoyevsky quote: “The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.” They had a Picasso painting in one of the mess halls until somebody finally realized what it was and stole it. I stole first-edition Samuel Beckett books from the library and mailed them back to my father. I dunno, dude. I haven’t thought about this shit in so fucking long.

Shields: What kind of routine were you able to develop in Rikers?

Rosset: I never joined a gang even though they asked me to. I helped one big dude learn to read. My nickname was The Brain because I could read and write. That was it. It was a very sad place.

Shields: How would you narrate your foray into addiction?

Rosset: Well, being that my dad published Burroughs and gave me Junkie to read when I was in my early teens, and being that I was clearly damaged from the very beginning, it just seemed like a natural thing. My father was an alcoholic, his father was an alcoholic, his mother was an alcoholic. I think my mother’s father was an alcoholic. So, genetically speaking, there’s definitely that and mental illness rampant on both sides of my family. And I was socially inept and I decided long before I did heroin that I wanted to be a heroin addict. I thought it was very romantic. Then I was in boarding school. Some kid handed me a joint. I took the joint, I got kicked out. I didn’t even smoke the pot. That was the turning point. I was like 13.

Photo by MIchael Sharkey

Shields: How did you come to live in this house?

Rosset: I was working for a very rich Italian guy. And one of the things he owned at the time was a record label. So one day I’m sitting there, I’m the assistant, and this lady [named Mary] walks in wearing all black. [My boss] just says stall, delay. It turned out she was there because she was selling one of her pieces of art that was worth four million. Two weeks later she comes back, he told me to blow her off again. Finally, she’s like, who are you? Next thing you know, I’m telling her about Barney Rosset, who she knew immediately, knew all about Grove Press. I didn’t know at this point how eccentric she is. Then she said, do you wanna work for me? I needed some more money and I ended up here one day. I was just going to help her move boxes. I’m not talking five or 10, I’m talking 40. From the top floor of the townhouse to the top floor of here. She had two buildings. When we were done, she changed her mind and said to put them back. I finally had a meltdown and started screaming. She just sort of stood there like with this smile on her face and I’m not realizing that whatever I said, she liked it. So fast forward, I’m still living in this shithole apartment in Bushwick or somewhere, Bed-Stuy. And there are bedbugs. I can’t even come up with the money to pay the rent. And she said, I feel sorry for your cats. Why don’t you come and stay here for a week? I was just thinking very short-term. That was in 2002 or 2003.

Shields: When did she pass away?

Rosset: Less than a year ago.

Shields: How have you managed to turn it into the center of downtown theatre and magazine culture in such a short time?

Rosset: Gasda started putting on Dimes Square in people’s apartments. The guy who lives upstairs went and saw it and said to Matt, why don’t you put the play on where I live? I didn’t know any of these people. Once we did the first play, I saw the opportunity. That night, I met so many people in book publishing and writing, my head exploded. This is what I’ve been waiting for my whole life. And the other cool thing, I immediately realized that what I have been doing here would make Mary so happy. I’m fulfilling her dreams, not only my own. I know she is smiling wherever the hell she is right now. That means the world to me. As difficult as she could be, she saved my life by letting me live here, and she opened my mind to a world I wouldn’t have seen without her.

Shields: What time of day do you do your best writing?

Rosset: When a play is going on downstairs, sometimes that’s the best time for me to work up here. It helps me focus for some reason.

Shields: Besides Samuel Beckett, what other authors have meant a great deal to you?

Rosset: Balzac, I love him. Henry Miller. Dickens. I just love Sir Walter Scott. The Epic of Gilgamesh —

Shields: I had a fantasy of learning Akkadian.

Rosset: Me, too. I kind of like Henry James, but I can’t really read him — all the women I’ve loved are Henry James fanatics. I never read any classics until I was 40. I wish I wrote like Mary McCarthy, her reviews. Oh, did I ever tell you my dad passed on The Hobbit?

Ben Shields is the managing editor of Grand Journal.

Photographs by Michael Sharkey.