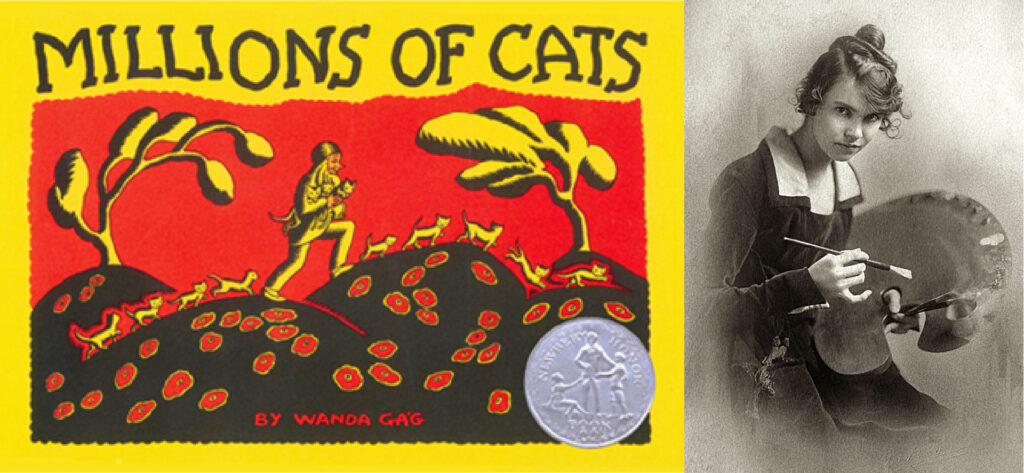

About the time that A.A.Milne began writing his tales of Winnie the Pooh and Christopher Robin, and 12 years before the arrival of Curious George, the Minnesotan artist Wanda Gag, the daughter of impoverished immigrants from Bohemia, was quietly, almost inadvertently, launching a revolution in book publishing. Her first title, Millions of Cats, the oldest American picture book still in print, was the touch paper for a new era in which children’s book were conceived, written, and illustrated by a single artist. Not many books, for children or otherwise, become a classic overnight, but Gag’s tale of “thousands and millions and billions and trillions of cats,” was a hit from the moment it came off the presses.

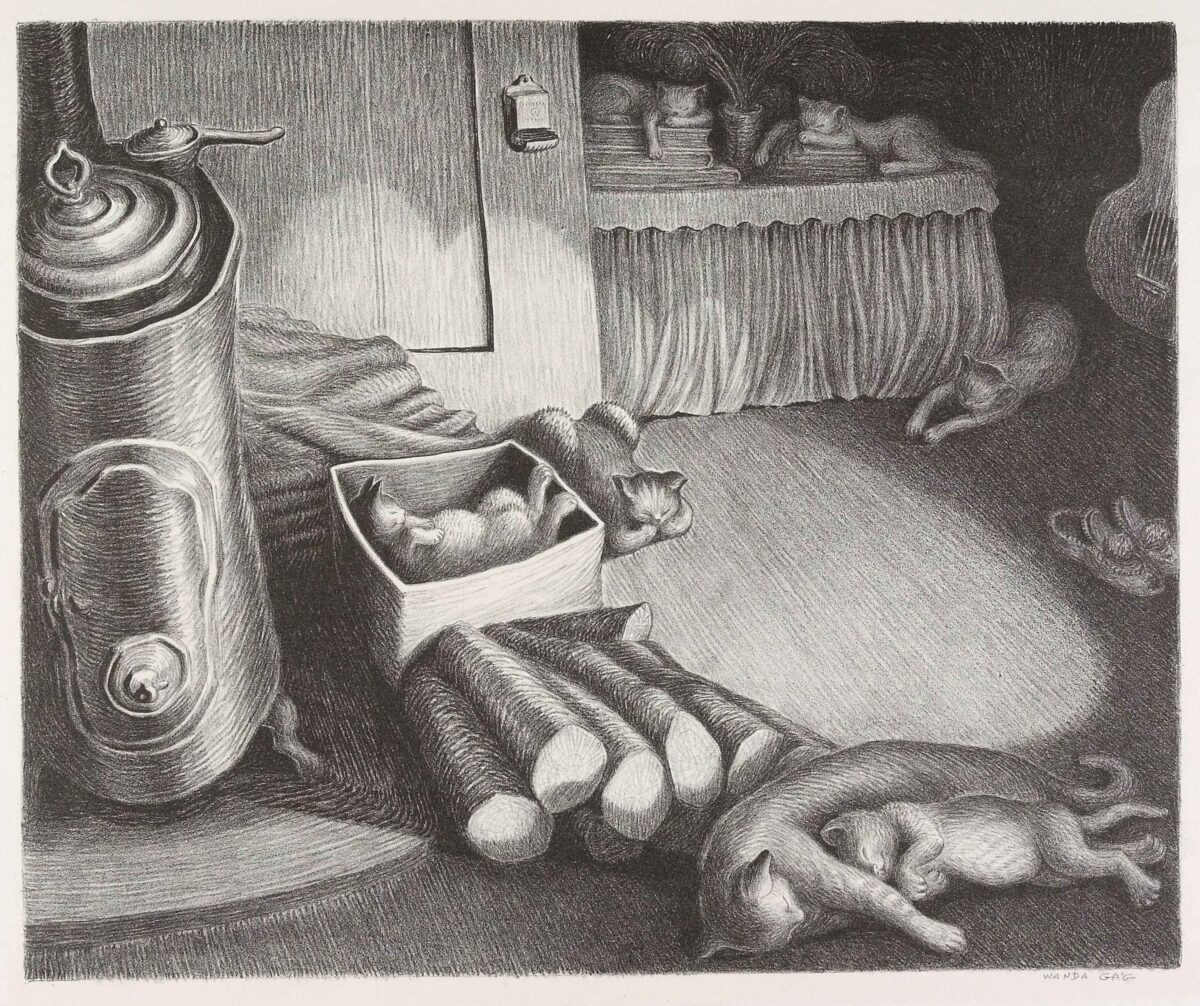

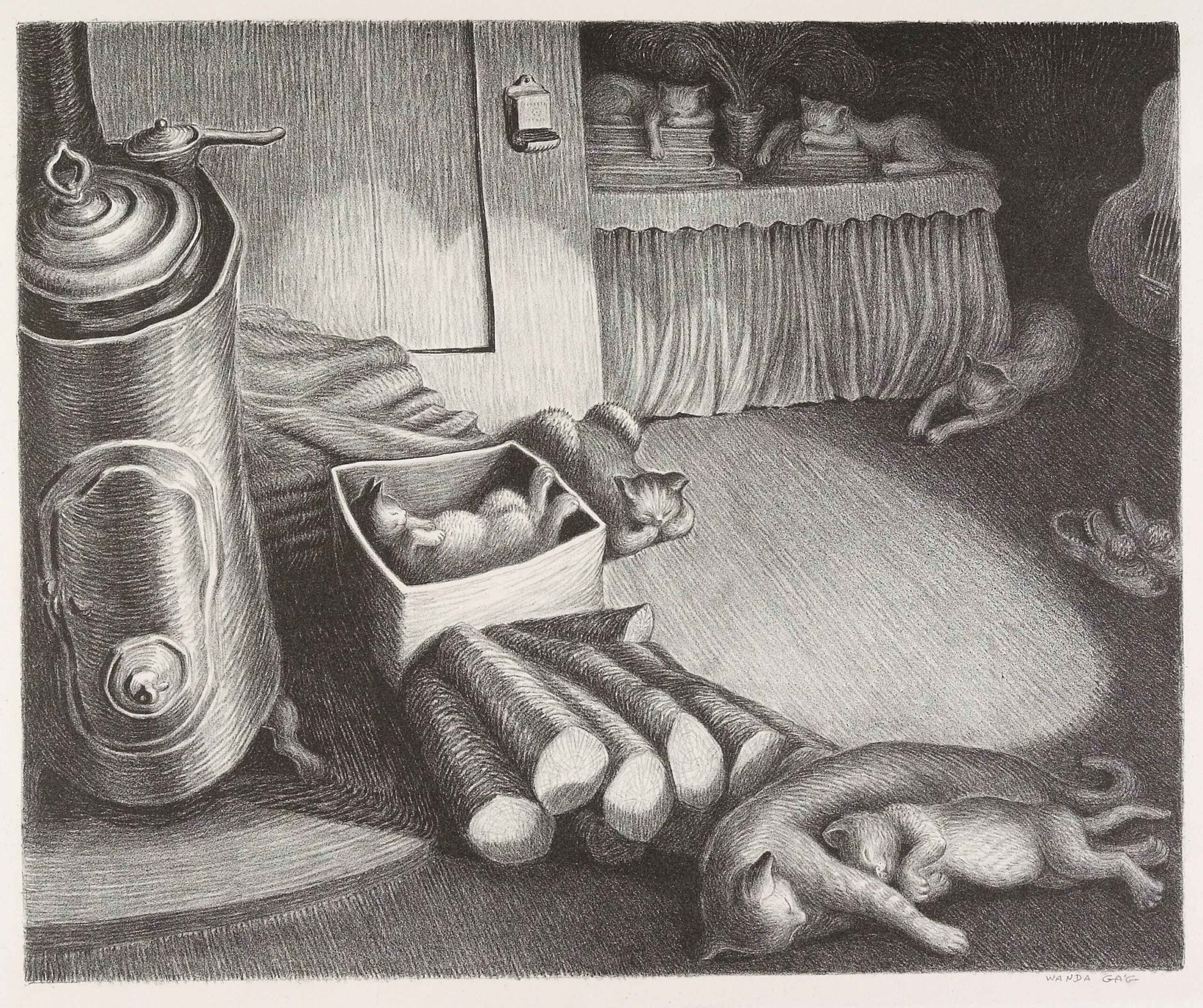

Gag’s books drew on nature and whimsy—a potent combination for children—but with a dark undertow that owed more to the Brothers Grimm than Hans Christian Anderson. In Millions of Cats, an old man’s difficulty in choosing one cat over another, results in chaos, as the cats eat each other in a fight to be the chosen kitty. In The Funny Thing a dragon dines on dolls heads. In Gone is Gone, a farmer’s belief that his wife’s labors would be easier than his own culminates in the family cow hanging from the roof “half-choked.”

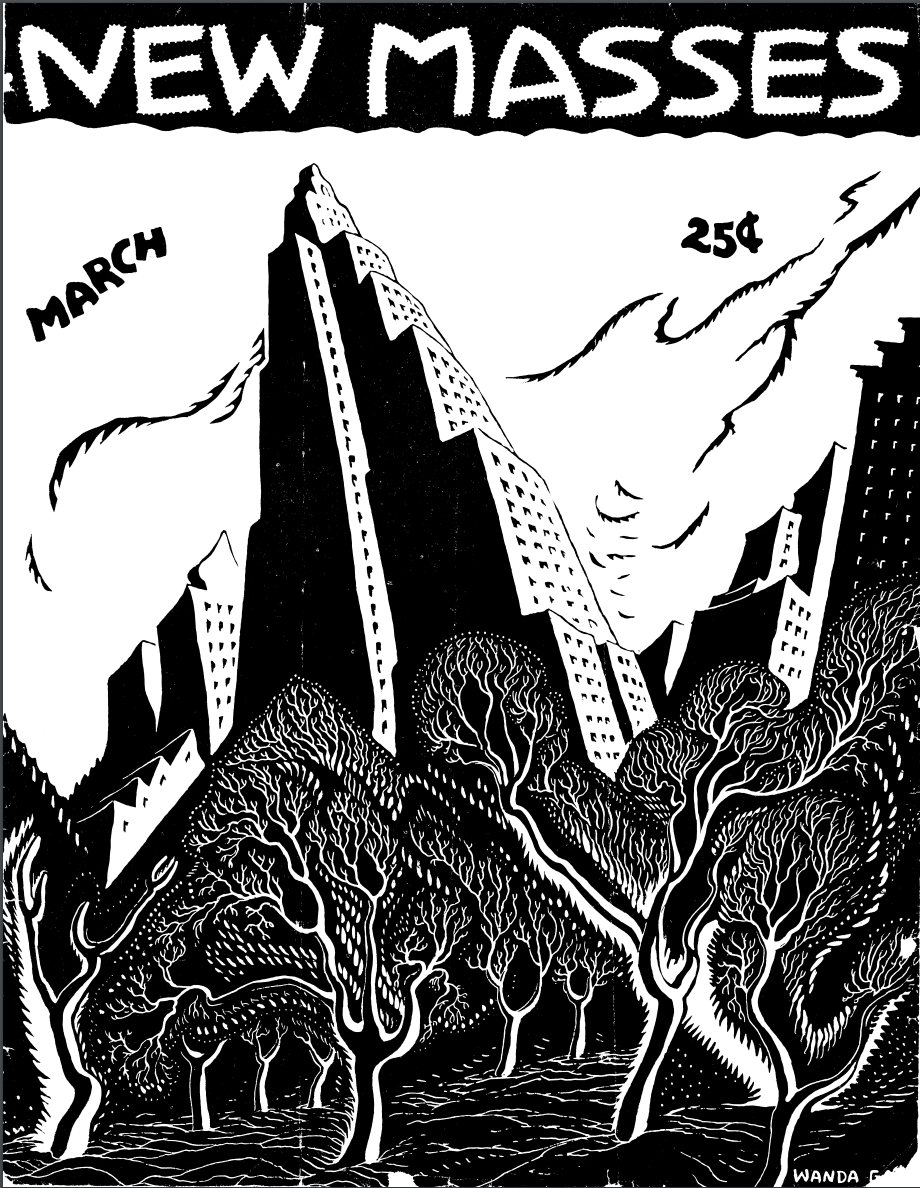

But Gag’s books weren’t just macabre, they had an “earnest regard for the underdog,” according to the American art historian Richard Cox. Gag had grown up in near-poverty in the town of New Ulm, Minnesota, so poor that she and her sister had to share a single sweater. Her ascent to fame and privilege did not inure her to the fundamental inequalities she experienced in childhood. In the 1920s and 1930s she was a frequent contributor to The New Masses, an American Marxist magazine that featured such writers as John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, and Ralph Ellison. Cox suggests the feline carnage in Millions of Cats reflects Gag’s revulsion of the ravages and loss of life caused by the First World War.

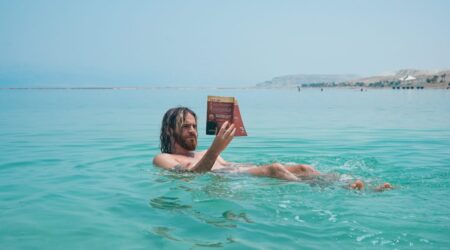

If New York fed Gag’s curiosity and appetite for intellectual stimulation, she also came to see it as the antithesis of the harmony she’d found in her childhood. In the mid 1920s, she relocated from New York to Connecticut, renting a farmhouse with the proceeds from a solo exhibition, and finding fame as a children’s author at the very moment that America was tilting into the Great Depression.

Through those thin and mean years her books continued to sell well, but she remained ambivalent about her new career, considering it mere commercial work. She continued, however, translating and illustrating Tales from Grimm, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and Three Gay Tales from Grimm. She also wrote a robust defense of fairy tales, arguing that “modern children” needed the fairy tale “since their lives are already over-balanced on the side of steel and stone and machinery — and nowadays, one might well add, bombs, gas-masks and machine guns.” She died of lung cancer at the age of 53, a year before the publication of her last collection of Grimm’s fairy tales. In her diaries, Growing Pains (1940), Gag wrote, “There is nothing better for us to do than to take ourselves as we find ourselves and make the best of ourselves.” It was a philosophy she never wavered from.