The stories of Helen Phillips and Etgar Keret take place in worlds that are both unsettling and absurd, if often similar to our own. Both writers have been compared to Kafka for good reason. In “The Knowers,” a short story from Phillips 2016 collection, Some Possible Solutions, a woman chooses to learn the date of her own death, and then spends the rest of the story (and her life) with the all-consuming event hovering on the edge of her consciousness. In “Tabula Rasa,” a story from Keret’s most recent collection, Fly Already, people pay to produce clones they can then kill. Both stories stray into the fantastic, but there’s something plausible about them, too. They speak to our subconscious desires and illuminate the ways in which we betray our better instincts and values. Phillips has talked about using surreal or speculative stories as vehicles to confront human experiences she can’t explore through realism. Keret’s Fly Already was inspired by a real-life car crash on the road from Connecticut to Boston in 2016 in which he broke two ribs and believed he was dying. “It occurred to me, that night in the E.R., that the fact that mortality and pain are the things that we all truly share was both comforting and sad,” he told The New Yorker. Mortality and pain flit like moths across the stories in Fly Already, a recipient of the 2019 Sapir Prize, Israel’s most prestigious literary award. They flit, too, across Phillips most recent novel, The Need, described by The Guardian as one of 2019’s “most necessary novels.” In it, a mother’s primal need to protect her children unfurls like a horror story before settling into a spiky meditation on modern motherhood.

Helen Phillips: Etgar, I loved your new collection, Fly Already, so much, and it was such a pleasure to read it. What do you see as the responsibility of the author to their characters?

Etgar Keret: In the end the only thing we can offer is a kind of sincerity, meaning that we are obliged to write about what we truly feel, not what we would have liked to have felt, or what we would have wanted to be like. We have to deal with the harsh reality of what we are. To me, this is combined with a mostly failing attempt to immerse this in some kind of positive force—to try to allow whatever I recognize in humanity or in myself, to come to it with responsibility, and say, Hey, maybe you can live a good life and maybe make sense, maybe you’re justified. But when you send this thing out, you don’t really know what you’re going to come back with. Sometimes you come up with stories that scare you.

Phillips: Do your stories scare you?

Keret: They scare me and at the same time they give me some kind of strength to deal with reality and life. Sometimes it’s hard to keep the characters’ human dignity, even if it’s in the most upside-down way. It’s really about believing that things can work. It doesn’t come from any resentment. It just comes from a failed attempt to get to a good place, or a better place.

Philips: One thing that lightens the gloom is the humor, which suffuses each story. What role do you see humor serving in your work?

Keret: I think if you slip on a banana skin and you hurt yourself then the only thing one can do is to make a joke about the situation. It’s the only dignified way out. Anything else—whining, yelling, complaining—and you’re not going to acquit yourself very well. A joke always implicates the fact that there is another level of existence, a meta-level. You have to look at things a little bit from the outside to be able to make a joke, and if you’re able to make a joke about the situation you are in, then it simulates a route out. Maybe it’s not a dead-end. For me humor is a reconciliation with life, an attempt to support something that is crashing and falling down.

Phillips: One hilarious and accurate moment I loved was in the story “Car Concentrate,” when the narrator describes what a conversation is: “A conversation is like a tunnel dug under the prison floor that you—patiently and painstakingly—scoop out with a spoon. It has one purpose: to get you away from where you are right now.” Do you think that the purpose of conversation is always to move us away from where we are right now?

Keret: Not only conversation, but storytelling also has the same function. We want to be immersed in a story to find ourselves in a place that is more vivid and more meaningful, and full of smells and sensation than the world we are in physically. There is this idea that if everything were okay, there would be no need to open our mouth. To call somebody, or to complain, or to threaten really doesn’t contribute to the equilibrium. It’s only when we get out of balance that you start waving your hands in the air.

Grand Journal: I’m really stuck on the idea of salvaging our dignity through humor. I’m thinking of the political moment we find ourselves in, and I’m wishing that politicians had that ability that writers seem to have: to be able to laugh at their failures and weaknesses.

Keret: George W. Bush had a great sense of humor. Really! I remember once when he was with Arnold Schwarzenegger and he said that they are very much alike because they’re both tough guys who don’t speak English very well. I even remember when someone threw a shoe at Bush, the expression on his face when he ducked. He was genuinely happy and amused. It was like a game, and he was able to duck in time. I never endorsed his politics, but I remember those moments that made him human.

Phillips: Speaking of American presidents, Trump has a couple cameos in the collection. In “Arctic Lizard,” he is now in his third term of his presidency, and you also mention Mark Zuckerberg in “Good Deed,” one of my favorite stories of the collection. I wonder if there is anything you would like to say about these notable Americans, or if you don’t want to say anything at all.

Keret: Trump symbolizes something in our reality and he seems to be almost passive in his role. Some leaders fight their way to power, but Trump stumbles into it. He is stuck in the entire system. There is something about Trump, if you want to think in an apocalyptic way, that symbolizes the fact that we have kind of given up on all those liberal and democratic ideas. It might just be something that happens, this ever-changing pendulum that humanity goes through, but at the same time it’s easy for me to think of Trump as something that predicts a world that is less fair and less liberal, and less considerate of people’s rights than it is even now.

Phillips: Your stories often ask ethical questions, and in “Good Deed,” one of my favorites, you examine the ethics of giving. There is this interesting twist where the need of the giver to give outweighs the need of the receiver. Similarly, in “The Birth of a Failed Revolutionary,” there are also ethical questions related to ownership, and people in desperation sell their birthdays to a very wealthy man. Both of these stories felt like parables to me, addressing questions of ethics in fiction. What role do you think ethics play in fiction and how central is that for you?

Keret: I very rarely think about ethics directly though when I write stories I often put my characters in situations where they have to choose between two things. That itself sometimes says something about right and wrong, but I really don’t write from any need to educate. It’s more about putting a spotlight on an area that is tricky, like lighting something that is broken on the floor. Sometimes an ethical question surfaces, but it doesn’t come from that.

Phillips: Simply shining a light on a question is the ethical act, even if you have no answer or direct ethical agenda at all.

Keret: Why do we do certain things is a question that I constantly ask myself, not just when I write. When I’m in a situation I try to understand why I did what I did, and why did other people react the way they reacted. The stories often take some kind of emotional trajectory that I didn’t anticipate.

Phillips: A lot of the stories in the collection are in the first person. What do you find to be the benefits and possible downsides of writing in that first person voice?

Keret: It’s funny, I always used to think that stories that came from some kind of visual experience become for me third person stories, because it’s something I saw. And all those experiences that had to do with voice, or with someone speaking, they turn into a first-person narrative in my story because you take that voice in and grow with that voice. Now I see that the division isn’t quite so clear. There is something about the character’s tone of the first-person narrative that dictates the plot. Sometimes through the language, you discover an aggression or frustration, or something beautiful, and in this way the voice or the tone creates the character, and the character dictates the decisions that are being made in the story.

Phillips: One thing that I find so powerful about first person is that you’re learning about the character not only by what they tell you, but also how they say it, in a way that is hard to achieve in close third.

The sentence “I wanted to bash his head on the table, but I didn’t” sounds very different in close third: “He wanted to bash his head on the table, but he didn’t.” There is something about the first person that brings an extra layer of urgency or implication to it.

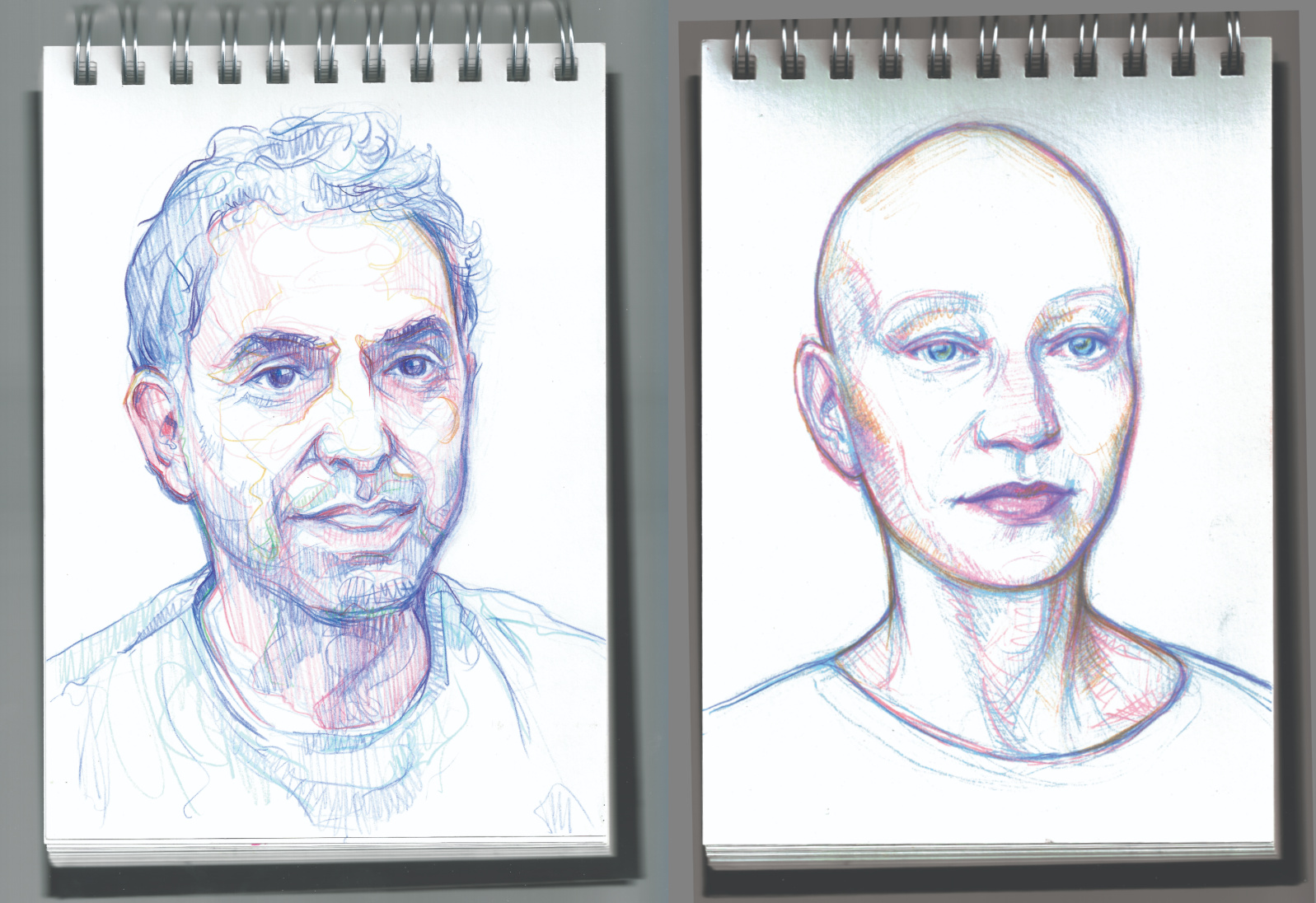

Helen phillips

Keret: I totally agree with that. In a first person narrative, many times you share with your characters the actions they refrain from taking. So the character can say, “I really wanted to bash this guy’s head on the table… but I thought about my father and I didn’t.” You can appreciate the character for what they didn’t do, or feel sorry for them because there was something they wanted to do but stopped themselves from doing, though the intention was there. You’re much closer to the intention when you write in first person. It’s a way of reminding people that though people cause the worst kind of things, they’re not really evil in the religious sense, but there is something there that can be twisted and painful, but if you look inside you recognize feelings that you know.

Phillips: Yes, it facilitates a certain relatability. The sentence “I wanted to bash his head on the table, but I didn’t” sounds very different in close third: “He wanted to bash his head on the table, but he didn’t.” There is something about the first person that brings an extra layer of urgency or implication to it.

Keret: Also, again, there is intention. In first person when you say “I wanted to bash his head,” there is passion and intention in that sentence. There is a realization of the situation.

Phillips: In contrast to the first person stories, there are stories in this collection that tilt towards science-fiction and questions of artificial intelligence. At the end of both “Tabula Rasa” and “Windows,” there’s a twist at the end, and the reality we thought was true proves not to be true. What do you think of our relationship with artificial intelligence and how those stories speak to that?

Keret: Those particular stories work as parables for something else. For example, romantic relationships between robots and human beings, or the ethical problems that come with cloning, those issues sound scientific, but they’re all about xenophobia and inequality. So when I write a story about how clones don’t have any human rights and can be killed, then basically I’m saying how some people are valued much less than others. It’s not necessarily a way of thinking about technology, but it’s some kind of leverage to speak about questions we are forever interested in.

Phillips: It’s a metaphor for current questions, and not about the future so much.

Keret: Yes, not at all.

Grand Journal: I also loved Tabula Rasa. I read it as a parable on the desire for revenge, and perhaps about a dream many Jews have about killing Hitler. Your grandparents perished in the Holocaust. Did the story speak at all to your particular family history?

Keret: I must say that if there is anything I learned from my parents, both survivors, it was really to not be enslaved by hatred and to try to seek humanity anywhere. One of my parents’ best friend was a German soldier in the Second World War. When the war started this man didn’t join the SS or the Gestapo, but fought in the North African front, and my father said he could imagine himself making the same decision. I think people who did not go through this period of history, or didn’t know people who were there, instinctively tend to take the stories and turn them into something more simplistic, a story of good and evil without human failure, without unexpected things happening. With my father, when we talked about the Second World War, he said, These were the worst years of my life but they were years of my life – the first girl I kissed, the first cigarette I smoked were during those times. They were horrible but they were life. I think this narrative is more intuitive to people who are closer to a reality, no matter how horrible it is, than to somebody who sees it from a distance.

Phillips: You see it from a distance, and you oversimplify, but if you live through it you understand all the nuances of it.

There are a lot of children in the book, including tense moments between fathers and sons, in particular in “Fly Already.” You have a child yourself. What role do you feel children play in your work?

Keret: I think that what I like about father-son relationships is this feeling of some kind of time change. The son is about to become something else, and this dynamic always provides a good story. If you want to create a landscape you are drawn to a hill which creates some kind of change; the same goes for this kind of age difference and difference in position, being two sides of something that is totally asymmetric.

Phillips: Our children provide a link to our past and future. I feel this very much with my children, also. There’s a certain time travel element when you are raising another human.

Keret: Sometimes you see your child and you recognize something of yourself in him or her. You see a trajectory where things end badly, one way or another. The compassion we have for our children is actually a reminder of how confined we are. You want to give them something, but you realize that there is nothing around to give. It can be heartbreaking sometimes.

Phillips: Yes, you confront your own limitations in a really direct way as you raise children.

Keret: There is something beautiful and frightening in humanity. We’re constantly struggling while trying to pretend to the outside world that everything is OK. It’s never OK for anybody. It’s always this kind of never-ending challenge and it’s very tiring. Of course, it’s also beautiful and happy, but it’s not going to become easy.

Grand Journal: Both of you being parents, how have your children given you material for stories?

Phillips: My book, The Need, is very much shaped by the experience of parenthood. For instance, you’re spending a lot of time with a person who does not know about death. They’re encountering language for the first time. They’ll figure out weird rhymes. I have alopecia so don’t have hair, and I once said to my daughter, “I used to wear fake hair,” and she said, “Oh yeah, and I go to daycare.” I had never thought of that rhyme. Having children delivers language and entire emotional realms to you freshly. Telling your children about death forces you to reconfront your own experience of learning and thinking about death. It’s really powerful in all sorts of ways that are both terrifying and beautiful. I do find that when I write about children, there is a direct path to what is primal about us and our emotions.

The moments when you feel you have failed are so private that in the best scenario you acknowledge them, but you don’t share them with others.

Etgar keret

Keret: I always felt warmth and compassion in the parental relationship as a child, but the thing that has changed since I became a parent is that I realize that the child takes for granted that the parent is the authority. He tells you what you can do and can’t do and sometimes the parent is wrong and sometimes they are right, and as a child you think, Ok, these are the rules, this is how it is. And when you become a parents you really start to question the tyrannical aspect of your position as a parent. Sometimes when you’re tired you break the rules. You may say, ‘No pizza,’ but then you may really feel like eating pizza, so you say, ‘Ok, it’s Saturday today, so we can have pizza.” You become a kind of corrupt monarch. There’s complexity in being an authority but at the same time not exploiting your authority in unfair ways. There is a hesitation inside each parent where you need to project the idea of authority but inside there is hesitation. The moments when you feel you have failed are so private that in the best scenario you acknowledge them, but you don’t share them with others. It could be when you told a little lie, or gave a bad answer. Those kinds of things happen all the time, and it’s basically like wearing a bulletproof vest, and the bullets keep hitting you, and you have to keep on going.

I had so many moments when I discovered there is something I can do or say when my son looks up to me, and see me as a great dad. It became very tempting to abuse it, or manufacture this effect when it was not justified. You really can come to depend on that reinforcement, that smile or hug, to confirm that your kid is looking up to you.

Phillips: That reminds me of a passage in your story “Ladder” where the angel is dissatisfied because angels don’t want things, and the angel featured misses the feeling of wanting things, and he says, “You know that feeling of wanting something so much that your whole body aches and you know that your chances of getting it are really, really small, and you stand in your living room in your boxers, covered in sweat, and try to imagine that moment when your lips will meet the lips of the girl you’ve always wanted, or your son saying, ‘You’re the best dad in the world,’ or the hospital calling to tell you the biopsy was negative? Did you ever want something that badly, Raphael?” I love that the father wants the son to say that he’s the best, and that to not have that desire – for another person, or to bring joy to your child – is devastating.

Keret: That power can also be very negative, because what you wish for is the effect. You don’t really want to be a great dad. You just want to be told that you’re a great dad.

Phillips: My daughter can now read, and there was this parenting book lying around our house, and she started reading from the book and giving me advice from the parenting book.

Etgar: The interesting thing about parenting books is the discovery that your parents didn’t know everything in the first place.

Phillips: When I’m trying to navigate a conflict between her and her little brother, she’ll say, “This isn’t what the book would say. This is what the book thinks you should be doing.”

Keret: She should become a lawyer. She’ll throw the book at you.

This conversation originally appeared in the Fall/Winter 2020 issue of Grand Journal.