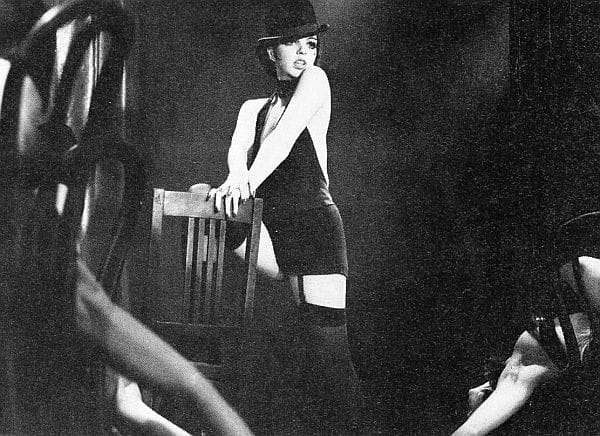

Few writers have shaped our cultural imagination quite like Christopher Isherwood. His Berlin stories gave us Sally Bowles and ultimately Cabaret, but his influence extends far beyond Weimar. Across novels, memoirs, and diaries, he chronicled the anxieties of modern life, the search for spiritual meaning, and the long, difficult journey toward queer liberation.

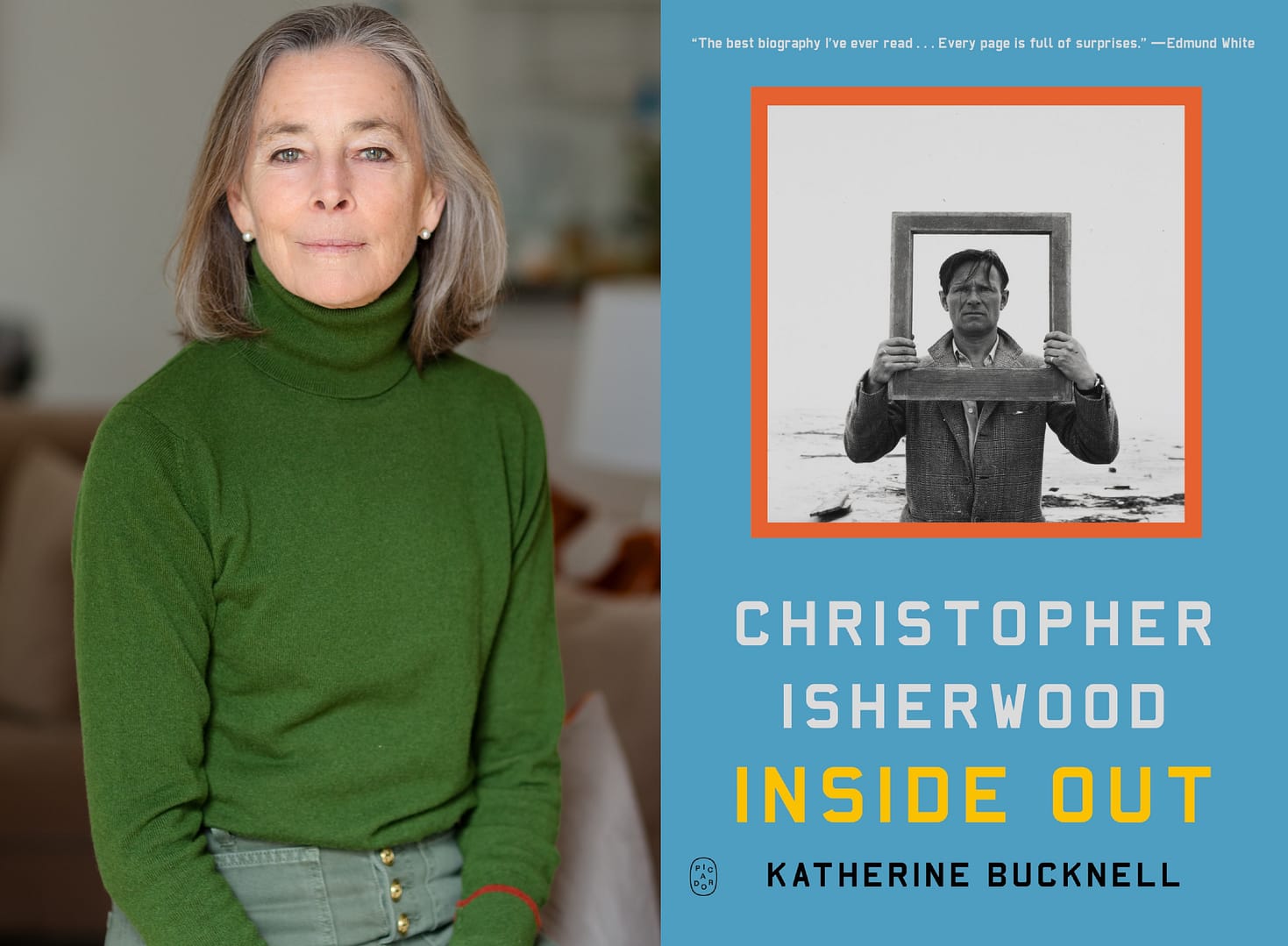

Katherine Bucknell has devoted decades to Isherwood’s world. She has edited four volumes of his diaries, assembled his letters, and now published Christopher Isherwood: Inside Out, a monumental 800-page biography that attempts the impossible: to capture a man who reinvented himself endlessly, yet remained, as she argues, “on the run from fear” his entire life.

For an episode of Shelf Life, we spoke about childhood trauma, great literary friendships, the allure of Berlin, the afterlife of Sally Bowles, and what Isherwood can still teach us about the pursuit of love and freedom. This is an edited version of that conversation.

Aaron Hicklin: You’ve spent much of your career editing Isherwood’s diaries and correspondence. One might think that four hefty volumes would be enough, but now you’ve written a vast biography. What did you want to achieve with Inside Out that you couldn’t as an editor of the diaries?

Katherine Bucknell: I wanted to tell the joined up story all the way from the beginning, and all the way to the–well, not end, because Don Bacardi, his partner, is very much still with us–but I felt that the aim of his life was always to seek a pattern and to find meaning. And the way that you do that is by assembling as much detail as possible, looking for acts and consequences, looking for an inside story. The more you have in the picture, the more you can see what patterns there are.

AH: The prologue of Inside Out opens rather deliciously with Isherwood sailing into New York Harbor in January 1939—a very auspicious date, of course—with a handsome boy in every port, as it were: a heartbroken lover left in London, another in Cambridge, a third serving hard labor in Germany. And a rent boy waiting for him on the New York pier. This is a hinge moment for Isherwood’s life. The end of his time in England and Europe and the beginning of his time in America. But you also use this first paragraph to put Isherwood’s sexuality and his relationships at the forefront of Inside Out. That seemed to me like a very conscious decision.

KB: Yeah, it was. There are so many reasons, but certainly when I began writing this book about 10 years ago, it seemed really important to make clear that the guiding motive in his life was to find personal happiness. And for him, that meant finding a partner, an ideal partner, and to find a way to settle down in a long term relationship. And that is a subject of his work. And for the LGBT community, it was a trajectory of the last century into the beginning of this one: how to find a way forward to live happily and openly in a community where, where you feel comfortable.

So, that seemed like a really big story. Another thing: I am a straight, married woman with kids, so what am I doing writing a book about a gay man? For me it was a gigantic challenge and, I would say, a mind blowing inner journey to engage with someone so different from myself. And I wanted to bring readers like myself to this book because certainly it was Isherwood’s own project to be in the mainstream. He didn’t want to just be writing books for people like himself. He wanted everyone to understand what it was like to be him, or someone like him, in terms of his sexuality. So I wanted to get that right out on the table in the beginning. Also, it’s sexy, it’s alluring.

AH: You say in the prologue that Isherwood had been on the run from fear ever since he could remember. What was the source of that fear, aside from homophobia itself?

KB: He was a fat, happy baby, much loved, but very early he began to suffer what we would call panic attacks—hysterical anxieties triggered by thunderstorms, rides at amusement parks, or even playground rivalries. His imagination was so powerful it could overwhelm him. But the defining trauma was the death of his father in World War I. Frank Isherwood was killed at Ypres in 1915, when Christopher was only ten. His mother, Kathleen, was devastated; she never recovered. The family didn’t even know for months whether Frank was dead—he was first listed as missing—so the uncertainty only deepened the anguish.

At the same time, Christopher himself nearly died from measles and pneumonia. He was delirious with fever, unable to eat for days. So you have a boy recovering from his own near-death while his father vanishes in the chaos of war. He must have thought: why him and not me? That confusion, coupled with his mother’s grief, left him terrified. He learned to control his emotions with extraordinary willpower, but the fears never really left him.

AH: Hi father does sound, on the page at least, like an absolute catch. He’s a handsome army officer, but also a very talented artist, a musician, an actor. You quote a letter from his father, while he’s fighting the Boers in South Africa, in which he says to Kathleen, Isherwood’s mother, “Even at my worst, I always carry my knitting.” I just loved that image of a man of many talents who didn’t seem to think of them in any way as effeminate or less masculine. This may also be something that shapes Isherwood, the fact that his father being so present to the arts.

KB: Absolutely. And actually, you’re on to something there. W.H. Auden thought that Isherwood’s father was even more original, more eccentric than Isherwood’s mother. They were both remarkable people. But yes, Frank, could play the piano, he could act, he was a painter of professional standard. He nearly left the army in about 1912 to become a professional painter because he was selling his work. And he had extraordinary personal energy and magnetism. I discovered, for example, that Christopher’s younger brother was conceived just after Frank had twice gone to London to see Strauss’s opera Salome. He was so excited by it he insisted his wife attend as well. Soon after, she was pregnant. That detail tells you something about Frank’s vitality and his embrace of art.

AH: Isherwood seems to have been a voracious reader, absorbing everything from Dickens to Dostoevsky to pulp detective stories.

KB: Yes, he gave himself completely to his reading. His mother read Oliver Twist to him aloud during the anxious months after his father disappeared. Imagine: a boy who has just lost his father, listening to his mother’s voice telling the story of an orphan surviving the cruelties of the world. He identified with Oliver and with his mother simultaneously. Later he did the same with David Copperfield. But he also devoured detective novels, pulp fiction, anything he could get his hands on. He treated every book as if it were happening to him. That apprenticeship as a reader shaped him as a writer. He learned to weave together high literature and popular culture, to spin what I call “gossamer threads” from many sources into his own distinctive twine.

AH: I was struck by a certain kind of contradiction or conflict which is that while the first part of the 20th century, and into the 1960s was a terrible time to be a gay man, punishable by imprisonment, and ostracized from many of your peers, there’s a strange sense in which boys of Isherwood’s class, particularly teenage boys, flirt ostentatiously with each other at school. Isherwood always seems to be having dalliances with other boys, and was in love with at least one boy. I was very amused to read of this bygone practice of school boys gifting each other studio portraits of themselves. Christopher was so popular at Repton, his prep school, that he wrote to his mother to, “send half a dozen more as they seem somewhat in demand.” How does challenge my notion of how repressive it was to be gay at that time?

KB: You know, that seems like a subject for a book in itself. How hard was it to be gay? In the first part of the century, each British publish school had a different set of rules for what kind of friendships were allowed between boys and how you would be caught or punished. And depending what school you went to you had a different situation to deal with, but the, tradition of teaching classics at all the public schools and universities enshrined Greek love as something that could be idealized and admired and accepted in a men-only setting. At Cambridge University, where Isherwood was for a little while before he got himself bounced out on purpose by flunking his exams, I got the sense that it was very free and flirtatious, including probably plenty of actual sex.

When he was at Cambridge, he read Frank Harris’s biography of Oscar Wilde in November, 1924. Honestly, it freaked him out. He was completely riveted by it. He sat all alone in his best friend’s rooms, drinking tea and eating toast, totally sucked in. And he had a kind of crisis thereupon. It was clear that he did not want to suffer the fate that Oscar Wilde had suffered. Wilde made the decision that he was not going to leave England and flee to France, even though there was time after he lost his libel trial to get away. His friends advised him to do it. His wife begged him to go. He wouldn’t go. He was a bit like Socrates saying to Crito, “I’m going to drink the hemlock. They told me I broke the laws of Athens and I’m not going to run from that.” Isherwood wanted to survive. He wanted to have a life. He decided very young that his would be a different pathway

AH: Let’s talk about the friendships that defined him. Edward Upward and W. H. Auden were constants throughout his life. Why were they so important?

KB: Both were literary friendships above all. With Upward, whom he met at Repton, Isherwood found the perfect rebel against the tyranny of the English public school. Later Upward became a dedicated communist, staying in the Party long after most had left. Christopher admired that commitment, even if it was misguided. With Auden, it was different: sheer intellectual electricity. They met on what’s called a Sunday walk when boys are paired off with one another and march through the countryside in their overcoats, probably when Auden was 10 and Isherwood was 13. That was the first conversation that Auden remembered in later life. They reconnected in London in the mid-1920s, and began exchanging poems and ideas. Auden fell in love with him—Isherwood never fully reciprocated, though they did sleep together—but the friendship endured for life. Auden pushed him to act on his sexuality rather than simply brood on it.

AH: Isherwood was devastated when Auden died, wasn’t he?

KB: Yes. Auden was younger, and Christopher always assumed he himself would go first. When Auden died in 1973, it shook him deeply. That grief partly inspired Christopher and His Kind, the memoir where he finally told the uncensored story of his Berlin years. It became a touchstone for gay liberation — suddenly the veils were lifted, the characters unmasked.

AH: Isherwood arrives in Berlin in 1929, already a published author. How did those years produce Mr. Norris Changes Trains and Goodbye to Berlin?

KB: He went for the sex, quite frankly. Auden had told him: Come here, there are all these brothels and boy bars and nobody’s controlling it. That was part of what was going on in Weimar; it was the sex mecca of Europe. Maybe you went to Paris for straight sex, but you went to Berlin for everything else. But what he found was more than sexual freedom. Weimar Berlin was intoxicating—art, architecture, theater, cinema, everything in flux.

At first he imagined writing a vast Balzacian novel called The Lost, weaving together dozens of characters. But after working on a film script, he realized the power of spareness, of focusing on a single figure. That became Mr. Norris Changes Trains, a blackly comic spy thriller based on Gerald Hamilton, a con man and political opportunist.

Goodbye to Berlin took a different form—fragments, diary entries, sketches, but actually it’s painting a picture of an entire political epoch. Out of those sketches emerged Sally Bowles, drawn partly from his friend Jean Ross, partly from stage lore, partly from his own imagination. She is, in many ways, Isherwood’s alter ego—brazen, alluring, but also vulnerable.

AH: Critics sometimes missed the seriousness beneath the comedy.

KB: Exactly. Isherwood’s great gift was to make us laugh at things we’d rather look away from. In Mr. Norris, you have torture and death alongside slapstick comedy. In Goodbye to Berlin, you have the rise of Nazism glimpsed through cabaret and gossip. Some readers saw only the entertainment, but others recognized the warning.

AH: Sally Bowles went on to have an extraordinary afterlife. First I Am a Camera, then Cabaret. And yet Isherwood famously skipped the Broadway premiere of Cabaret in 1966. What troubled him?

KB: He was professional about adaptations: if you bought the rights, you could do what you liked. He adored Julie Harris in I Am a Camera — she captured Sally so perfectly he could hardly remember his own conception of the character. But by the time of Cabaret, Sally had become something else entirely. Jill Haworth on Broadway, Liza Minnelli in the film — these were dazzling, but they had little to do with the girl he had known or imagined. By then Isherwood was still writing, still growing. To see himself turned into a stage character, “Herr Issy Vu,” was strange. He didn’t need to be near it. He let it take its own life, while he went on with his.

AH: After Berlin came America. How did California reshape him?

KB: Moving to Los Angeles in 1939 was transformative. Most importantly, it was where he met Don Bachardy, thirty years his junior. Bacardi was 18 when they met and Isherwood was 48, and right from the beginning there was something special and intense happening. And within this gigantic biography, here is yet a whole further story about meeting a young boy who is bristling with talent and alertness and physical magic and beauty and excitement. Isherwood gave him novels to read, took him to the ballet, took him to foreign movies, to New York, and on a grand tour of Europe. This is over a period of maybe the first seven years they were together. And there were many, many challenges to the relationship: 30 years difference in age, conservative Hollywood, the 1950s. How do you navigate that? And how did he protect their domestic privacy? And how did he protect this young boy and also Introduce him where he felt it was. safe. So he had a lot of responsibility and decision making to do. And Don was at Isherwood’s bedside, painting his portrait when Isherwood died of cancer in 1986. And one of Don’s greatest bodies of work is the last drawings of Christopher Isherwood, hundreds of them that he did over the last months of Isherwood’s life. So, these were two people who were completely committed as artists, completely committed to each other, and they became a very prominent model of gay partnership in the 20th century.

AH: And spiritually, he found Swami Prabhavananda.

KB: Yes, Isherwood became a disciple of Vedanta, translating sacred texts, practicing meditation. It gave him a sense of discipline and perspective, a way to confront that lifelong fear. At the time, many of Isherwood’s friends couldn’t believe it—they thought he’d lost his mind—but meditation and Eastern religions have come much more into the center of Western culture in the last 50 years, so I don’t think it’s so hard today for people to understand why this was such a good pathway for him to set out on.

AH: You mentioned Christopher and His Kind earlier. Published in 1976, it felt like a second, or even third, coming out.

KB: Absolutely. It was revolutionary. Suddenly readers could reread the Berlin novels “uncloaked,” as you put it, seeing the real people behind the characters. It became a foundational text for gay liberation, published at exactly the moment when people were ready to hear the truth. It made him famous all over again.

AH: You’ve spent a lot of your life with Isherwood, in a sense, if not with Isherwood in person, then through his work, through his letters, through his journals. How much do you feel that Isherwood is sort of in the room with you as his biographer?

KB: It is so personal to me, and he is so in the room, and I feel the privilege of that, and also the terrible worry, because who am I to be trying to channel someone who didn’t always get along with women? And maybe I’m like his mother, bossing him around and saying, “You’re this, you’re that.” And he might, if he were here, say, “I’m not this, I’m not that, you have no right to say these things.” So I take it really seriously. I find it really exciting. I think sometimes he’s trying to convert me to Vedanta. But he is who he is and I am who I am. I would never imagine that I could close that gap. So I just want to go on learning. Sometimes I will take down one of the novels and reread it and say, “Wow, I read this all wrong the last time.” I want to be confident that I’m doing something for him, but I don’t want to presume that I’ve got it right…. I think about him every single day, probably every hour.

Christopher Isherwood: Inside Out by Katherine Bucknell is available now. Support One Grand Books by ordering your copy at Bookshop.org. You can listen to the episode of Shelf Life here.