Maybe they are the most written about band in history, but in his new book, 150 Glimpses of The Beatles, Craig Brown demonstrates that there’s always something new to say about even the most overworked subjects. In this “glimpse,” Brown attends a concert by a Beatles tribute band and finds his skepticism quickly undone.

I arrived too late at the International Beatles Week in Liverpool to catch the opening act, Les Sauterelles. They formed in 1962, and according to the brochure, ‘soon became the most popular Swiss Beat Band of the sixties. In the hot summer of ’68, their single “Heavenly Club” was number one for six weeks in the Swiss Charts.’ Next up were a Beatles tribute band from Hungary called the Bits, followed by the Norwegian Beatles, ‘probably the world’s northernmost Beatles tribute band’, and then Clube Big Beatles from Brazil, who are apparently soon to open their own Cavern Club in São Paulo. Performers on the indoor stage included the Bertils from Sweden, the Fab Fourever (‘Canada’s Premiere Tribute to the Beatles’), Bestbeat from Serbia, crowned ‘one of the thirty most prominent Beatles tribute bands on the planet’ by Newsweek in 2012, and B.B. Cats, an all-female tribute band from Tokyo who specialise in playing the Beatles’ Hamburg repertoire. There are over a thousand Beatles tribute acts in the world today. Many of them – the Tefeatles from Guatemala, Rubber Soul from Brazil, the Nowhere Boys from Colombia, Abbey Road from Spain – have now been together longer than the Beatles themselves: Britain’s Bootleg Beatles and Australia’s Beatnix have both been going for forty years. In the evening, I joined the long and winding queue outside the Grand Central Hall to see the Fab Four from California, one of the most successful Beatles tribute bands in the world. Most of those queuing were around the age of seventy, which would have made them fifteen or so at the height of Beatlemania. The men wore baggy jeans and Beatles T-shirts; the women slacks and generous tops. One or two people were in wheelchairs. At most rock concerts, fans rush to get close to the stage, but when the doors to the Grand Central Hall opened, most people rushed upstairs, to where the seats were. A depressing man in jeans and a knitted bonnet opened the show, moaning his way through John’s passive-aggressive ‘Don’t Let Me Down’, accompanying himself with jerky pyrotechnics on an acoustic guitar. What was I doing there, with these senior citizens togged up in their Beatles gear? With a change of clothes it might almost have been a reunion of Second World War veterans, gathered for a fly-past of Spitfires. In the 1970s, my parents used to watch a TV program called The Good Old Days. The audience would dress up as Edwardians, the men in straw boaters, fancy blazers and walrus moustaches, the women in feather trimmed hats and voluminous dresses with high-boned collars. They would gasp adoringly as the high-camp Master of Ceremonies, Leonard Sachs, introduced each music-hall act – tap dancer, conjuror, barbershop quartet – with a stream of elaborate words: ‘Prestidigitational!’ (‘Oooh!’), ‘Plenitudinous!’ (‘Ahh!’), ‘Sesquipedalianism!’ (‘Oooh!’), and then banged his gavel. At the curtain-call everyone would join in with a sing-song of ‘Down at the Old Bull and Bush’. It was what was then known as a trip down memory lane, viewers at home happy to collude in the deception that time could be reversed, and the dead revived. Was this Beatles revival another quest for the same old thing – dreams of blue remembered hills?

That is the land of lost content, I

see it shining plain,

The happy highways where I went

And cannot come again.

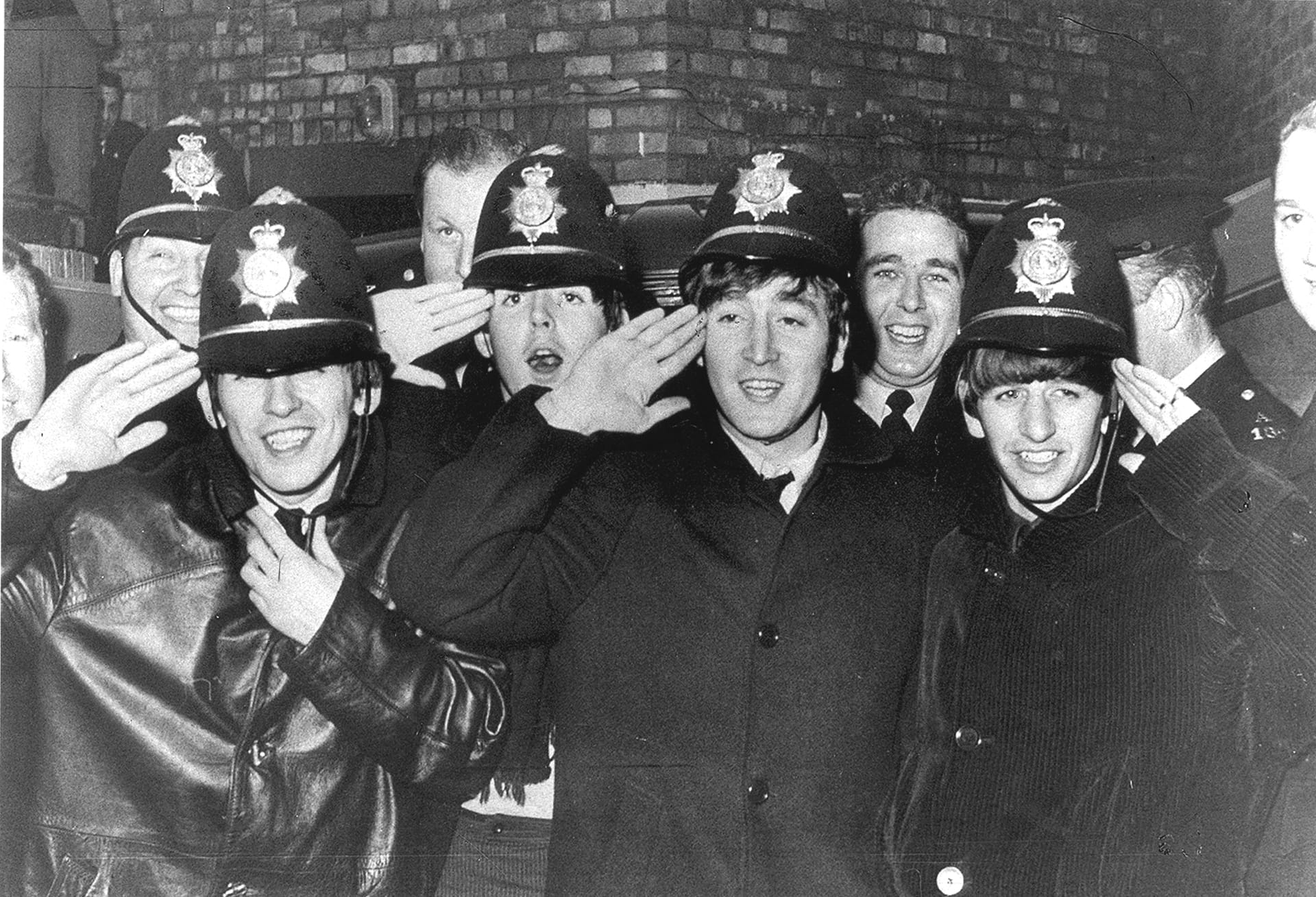

Such were my maudlin reflections as the Fab Four took to the stage. But then they started to play ‘She Loves You’, and they sounded just like the Beatles and, to my fading eyes, looked just like them too – Paul arching his eyebrows and rolling his eyes to the ceiling, George slightly dreamy and distant, Ringo rocking his head from side to side, John with his legs wide apart, as though astride a donkey. I was witnessing something closer to a wonderful conjuring trick. One half of your brain recognises that these are not the Beatles: how could they be? But the other half is happy to believe that they are. It is like watching a play: yes, of course you know that the couple onstage are actors, but on some other level you think they are Othello and Desdemona. The drama lies in the interplay of knowledge and imagination. And with the Fab Four, there is another illusion at work, equally convincing, equally transient: for as long as they play, we are all fifty years younger, gazing in wonder at the Beatles in their prime.

150 Glimpses of the Beatles is published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux ($30). To order a copy, go to onegrandbooks.com.