1: The Celebration of my Birth

I am the eldest son of a deeply traditional family from Raqqa, a city that was once enchanted. And still is… A city that stood alone on the banks of the Euphrates River. Anyone born there could live an innocent life, just as I did. Born in 1991, I brought the pride of manhood to my father and joy to my mother. I was the one who gave her the title Umm al-Sabi—the mother of a boy.

The women brought her luxurious fabrics—silk, organza, velvet, and embroidered textiles—along with elegant boxes of chocolates and kanava boards adorned with Quranic verses to bless her. It was as if she had become a bride again.

As for my father, a butcher by lineage and trade, he exclaimed “Allahu Akbar” over five rams before slaughtering them at the entrance of our home. Their thick blood flowed in streams across the dirt, running from our doorstep to the Euphrates River, passing the houses in Al-Firdaws neighbourhood, a district of grand homes built with polished white stone, where grapevines cascaded over garden walls.

My mother often told me (and her friends and the neighbours confirmed) that on the day I was born, God blessed all Raqqa with the first rains of winter. Torrents of water joined the sky to the earth, a heavy rain that rivalled the Euphrates in its abundance. It washed and gave succour to the trees, and most importantly, it cleansed our streets of the blood of the sacrifices. Otherwise, the blue flies would have outnumbered people that day.

Although my father chose to name me after his own father for the official records, I became known as Matar or “Rain” in tribute to the deluge on the day of my birth. The women washed my newborn body with water and salt, rimmed my eyes with thick black kohl, an age-old Euphrates tradition to protect infants’ eyes from infection. Then they placed me beside my mother on her bed. Well-wishers poured in, decorating my chest with golden medallions and blue beads. It was said that Abu Imad, the local jeweller, had never sold so much gold in a single day.

2: The Circumcision Ceremony

My mother delayed my circumcision for seven years after my birth. Not because she feared they might accidentally cut off my penis, but because she was waiting to have another son. She envisaged a grand, collective circumcision ceremony for me and a brother. After me, my mother gave birth four more times, but each child that emerged from her womb was a girl. She lost the title Walladit al-Sibyan—the bearer of boys.

In truth, it felt like an answered prayer of mine, as each new birth postponed my circumcision. Yet, my father and mother were convinced they’d been struck by the evil eye. To ward it off, they adorned our house, inside and out, with blue stones. My mother began burning incense every Thursday night, carrying a bowl from which thick, aromatic smoke rose and filled the house—pleasant, yet suffocating. As she did this, she recited the Quran aloud: “to deliver from the evil of the envier when he envies.” She would pray fervently for God to plant the seed of a son in her womb. To me, she looked like a sorceress performing spells. I’d hide behind the curtains until she finished.

Meanwhile, I could do nothing but stare at my circumcised cousins’ genitals when we swam naked in the Euphrates River. I’d compare their smooth organs to my own, which resembled a tiny elephant trunk. Hadn’t I always been fascinated with genitals, even as a child?

My father, on the other hand, was constantly bombarded by comments from his brothers and friends:

“Circumcise your son—he’s almost a man now.”

“Do it for hygiene.”

“Look at him. Doesn’t he look like Abu Imad the jeweller’s kids?” they’d tease, referring to our Christian neighbour and his children.

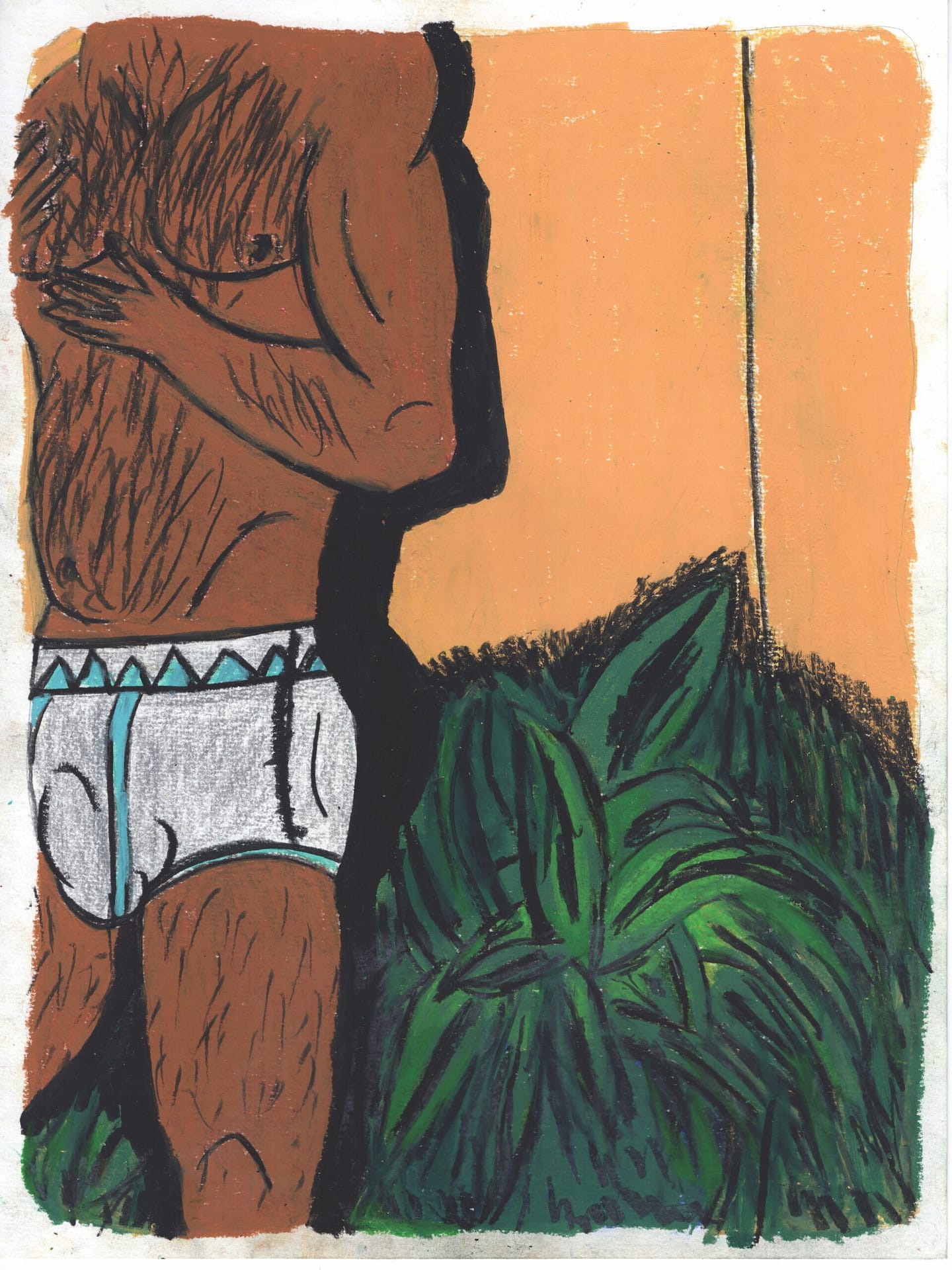

My father arranged with the Saffouri—the circumciser—to come on a Friday and cut the skin off my member. I couldn’t sleep the night before. Under the covers, in the dark, I pulled down my underwear and couldn’t take my hands off my penis. My fingers played with the skin that hung from its tip, measuring how much of my body I was about to lose. Like a blind man, I memorized its shape with my fingers to etch it into my memory.

The next day, one of the hottest days of that summer, we all woke up to the sound of drums, flutes, and the bleating of sheep filling the street. My father had hired a band to “spread joy throughout the neighbourhood” and brought five sheep to be slaughtered. He normally expressed his joy by sacrificing the sheep and distributing their meat to the neighbours. All that noise and celebration was so that everyone would know that Matar, his only son “after four daughters,” was finally getting circumcised. Guests arrived, singing and dancing outside our house.

Meanwhile, I was enduring my first real inner torture. I struggled under the covers, crying in fear of the forthcoming operation whilst my body swayed to the rhythm of the drums and flutes.

My mother pulled me into the bathroom, singing and dancing as she washed my body with a white bar of soap, scrubbing me vigorously and transforming me into a fragrant jasmine plant. She called this my bath for eternity, warning me that I wouldn’t be allowed to touch water again until my wound healed completely. She recited some verses from the Quran, blew into my face, then dressed me in a loose white satin robe that she had sewn herself. This was the best part of the ceremony. I was wearing a robe that looked like a bride’s dress for the first time in my life. My mother decorated my chest with the same gold pieces I had received at birth. The Gold coins had holes for pins and were strung with blue beads wrapped in pure gold wires.

I asked her if wearing lipstick was part of the circumcision ritual too, but she told me to keep quiet, or I’d end up like the sheep outside our door.

Above them all, our ceiling fan spun ferociously. How I wished it would fall and decapitate them in their fervor.

In the living room, a high bed decorated with white pillows awaited me. My mother had prepared it for me, and it looked like a dovecote. Around the bed gathered my uncles, my father’s friends, the jeweller Abu Imad, the male neighbours, and even the imam of the local mosque. Above them all, our ceiling fan spun ferociously. How I wished it would fall and decapitate them in their fervor.

I had to remove my white underpants and hand them to my father like a badge of honour, then lie on my back in my nest, lift my robe, and bite its hem with baby teeth.

The men’s faces loomed over me, their eyes all fixed on my member. How I wanted to ask my father: Why doesn’t the imam go to the mosque, climb onto the minaret’s balcony, and announce to all of Raqqa to come and watch my penis? But my mouth was muffled by the fabric.

The Saffouri arrived with his black leather bag and knelt before me, leaving only his thick black mustache visible. I heard the zipper of his bag and the clinking of metallic instruments playing a dissonant melody. I felt cold drops falling on the head of my penis before I stopped feeling anything altogether. I tried to make out what was happening to my penis by watching the reflection in the men’s staring eyes. Finally, the Saffouri raised the metal scissors high, holding my foreskin like a small, bloody cherry. My mother’s ululations erupted from the kitchen, announcing the success of my circumcision.

The slaughtered sheep were hung above our doorstep, and my father began carving their meat, distributing it to everyone who came and sending portions to those who didn’t. My mother had to prepare a grand feast, as tradition demanded, tossing my foreskin into the pot to disappear among the chunks of lamb, which the men would eat. It was believed that doing so would grant me strength and authority when I grew up to become a man.

The anaesthetic wore off, and my penis began to throb in agony, as if my mother had seasoned it with salt and pepper. Meanwhile, the men around me tore into the meat with their teeth. The only thing that eased my pain was the thought that they were eating my penis – even the imam!

3: The Wedding Party

How could I reach my eighteenth birthday without getting married? That’s what my father told me in words that puffed up his lips. He also said that a man’s faith is incomplete without marriage and that it was time for me to complete mine before I fell into the sin of adultery. As I listened, my eyes fixated on his lips, and I thought: Why didn’t I inherit my father’s plump lips instead of my mother’s thin ones?

When my mother entered my room to show me pictures of brides I could choose from, she found me holding my eyelashes between my fingertips, lifting them upward, and pouting at my reflection in the mirror. Surprised by what I was doing, she asked me why. I told her I was practicing what our religion teacher had said in school: “God will hang anyone who looks at a woman’s body with lust from their eyelashes in Hell.” She agreed with me and said I urgently needed to get married. She didn’t have any other choice!

She showed me a collection of photos she had gathered—from our relatives, my father’s side of the family, and even the neighbours’ daughters. As she spoke about each girl’s virtues, I compared their lips. In the end, I chose the girl with the plumpest, cherry-like lips. She wasn’t a relative or a close neighbour but a stranger.

“God will hang anyone who looks at a woman’s body with lust from their eyelashes in Hell.” She agreed with me and said I urgently needed to get married. She didn’t have any other choice!

The same men who had feasted on my foreskin at my circumcision ceremony joined my father and me to ask for her hand in marriage. Her father agreed and the imam declared: “Let’s recite Al-Fatiha for good fortune.”

Behind our house and across from my school, there was a dirt square surrounded by tall palm trees. It was the local celebration ground, used for both weddings and funerals. If no event was taking place, it became a football field for the local kids. For my wedding, the young men volunteered to sweep the square, sprinkle it with water, and string up long rows of yellow lights that made night’s arrival almost imperceptible.

While this was happening, I was at the men’s salon, getting my hair cut and beard shaved. The barber told me that this was my night and that I was entitled to anything I wanted. So, I asked him to thread my eyebrows, apply cream to my face, and line my eyes with kohl. When he said he didn’t have mascara, I didn’t dare ask for lipstick.

I dressed in my suit at the salon—a black one with silver glitter scattered over the shoulders like stars in the night sky. The barber helped me do up my pink tie, despite my mother’s strong disapproval of the colour. Soon, the handsome young local men flooded into the salon, dressed in their finest suits, singing and clapping:

“May the groom of beauty find joy;

He commands us, and we obey.”

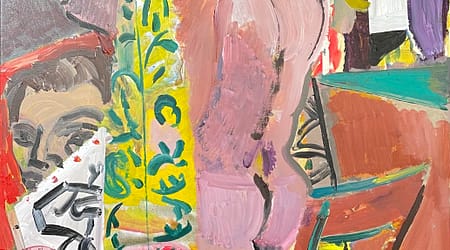

They carried me on their shoulders from the salon. As soon as they brought me into the square, now packed with women and men, celebratory gunfire erupted into the air. The crowd passed me from shoulder to shoulder above their heads until I was finally placed on a massive, gilded throne-like chair, fit for queens, next to my bride, who sat on an identical one.

I looked at her face, heavily painted with makeup. She must have asked the makeup artist to make her skin as white as her wedding dress. Her hair was dyed light blonde, styled into an enormous flower on top of her head and adorned with a princess’ tiara. Her wide eyes were lined Cleopatra-style, her cheekbones were high, but her lips weren’t as plump and thick as they were in the photo. That must have involved a trick with a contour pencil.

The music erupted from massive speakers planted in every corner of the square. I took my bride’s hand, lacing my fingers through hers so we could dance together. I was eager for this moment—she was wearing lace gloves, and I’d never felt lace before. I gripped her hands tightly and pulled her onto the dance floor. The lace clung to my fingers like iron to a magnet. We twirled and spun together until my fingers disappeared into the lace. The crowd clapped, shook their shoulders, and stomped their feet in rhythm. A circle of men and women surrounded us in the traditional dance of Raqqa: Men’s shoulders brushing against women’s, but not men’s against men’s.

Everyone wore their finest colours. The women wrapped their heads in vibrant scarves, letting their long, hennaed hair cascade over their shoulders. Their eyes were lined with black kohl that extended to the ends of their eyebrows. They wore gold nose rings and displayed intricate tattoos on their chins. Everyone danced, swaying to the music’s vibrations, and celebrating. Rice grains were tossed over us from elderly women’s trays, along with coins and candy. The air filled with ululations and gunfire. Even the children joined in the joy, rolling between our feet to gather the coins and sweets.

“Isn’t it all so adorable?”

No, it wasn’t adorable at all! Inside me, a massacre was taking place. Every bullet fired into the air landed in my heart. I was a groom with a dead heart, and this celebration was my funeral. I didn’t fit in with anything happening around me. I spun with my bride in my arms, closing my eyes to see the barber’s fish-like green eyes staring at my shiny black hair. I gazed at his thick brown beard and the chest hair peeking through his shirt’s opening. I felt his fingers pulling my hair firmly, while under the barber’s cape, my hand inched closer to the armrest of his chair, hoping to graze the crotch pressed against it.

My heart quivered in my chest, and I came back to life but I opened my eyes and found myself a cold corpse next to an innocent victim called “wife.” I didn’t know if I had killed her, or if my parents had, or if tradition had… or perhaps the imam, when he recited Al-Fatiha.

My father told me that marriage would complete my faith, but every night I lost part of it. Each time I imagined the barber naked in my mind, joining us in bed, my circumcised penis would stiffen.

4: The Celebration of Fall of Raqqa

My wife didn’t have big lips, but she had a big heart, where I hid like a mischievous child. With her, I was myself. I applied her makeup, styled her hair, and had the freedom to involve myself in the minutiae of her life as a woman. I was close to her, with the right to touch and use her belongings. Our bedroom drawers were filled with lipsticks, kohl pencils, beauty products, and moisturizing creams. We even used the same apple-scented shampoo. Every night, she would apply crimson red lipstick before going to bed. Each time she did, she earned a passionate kiss from me, transferring all the lipstick from her lips to mine. And there was one more thing she doubled down on buying because it excited me—lace underwear. I started wearing it too, and she loved the feel of lace against my hairy body.

My wife introduced me to the concept of true friendship, and that became the most important reason for my attachment to her. I had never experienced friendship with anyone else. I didn’t finish school with a special schoolmate or attend university with a special college friend. I didn’t join the military service because I was an only son, so I never had a comrade-in-arms. Having a friend of the opposite sex never happened in Raqqa. I was lucky to have my wife by my side.

We watched TV dramas together, shared our morning coffee, and enjoyed the same morning radio programme. She washed the clothes, and I hung them to dry. We cooked together, laughed together, cried together, and visited the gynaecologist together, hoping he’d find a way for us to have a child.

After three years of marriage with no grandchildren in sight, my mother gave up hope. She wanted me to take a second wife, but this time I managed to refuse. I expressed my fear of hurting my wife’s feelings. That fear was a real emotion—fear of breaking her heart, because I was hiding inside it.

In 2013, my wife and I sat in our living room, watching the protests in Raqqa on television. Before us was a plate of nuts and chips, along with a pot of tea. It was as though we weren’t part of the same city. We lived inside a bubble. We didn’t realize we supported the demonstrations until we saw President Bashar al-Assad’s face on the screen, issuing threats in his speeches.

Our movements around the city dwindled. My mother started calling us more than ten times a day to ensure I hadn’t left the house, as the security forces were randomly arresting men to intimidate the residents. During those times, I clung to my wife more than ever, relying on her to buy everything we needed. She became the man I leaned on.

Every night, when the sounds of gunfire echoed during clashes between the Free Syrian Army and Assad’s forces, I would dig a trench in her heart and bury myself in it. By morning, it was she who ventured out to make out the chaos in Raqqa’s streets, asking vendors and passersby about the latest developments. She’d return with questions that seemed to have no answers: How did the extremists enter Raqqa? How did they get in? Who are Jabhat al-Nusra? And who will lead the city now that Jabhat al-Nusra has defeated the Free Syrian Army?

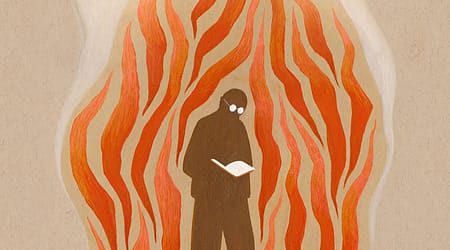

She would come home and relay the news to me. But in the mornings, I was like a bird losing more feathers each day—unable to fly or even gaze at the sky. At night, I became a fragile thread of black fear, always on the verge of snapping.

On a doom-laden evening, my wife came to me, speaking of men draped in black, their faces concealed, filling the streets of Raqqa. They didn’t speak to anyone, keeping their identities hidden. Their appearance resembled that of Al-Qaeda fighters—the Afghan men we used to see on Al Jazeera. I didn’t understand much about politics; my expertise was in makeup brands, application techniques, clothing stores, and fabric types. But I remembered the words of Bashar al-Assad in his 2012 speeches:

“Syria today is the centre of the region. It is on a fault line—if you tamper with it, you’ll trigger an earthquake. Do you want to see another Afghanistan or dozens of Afghanistans?”

Gunfire erupted in our neighbourhood, accompanied by cries of “Allahu Akbar” and the screeching of heavy vehicle tires against the asphalt. I approached the window of our apartment, lifting the edge of the curtain to steal a glance at what was happening outside.

They weren’t human. They were black-clad figures, masked and faceless, like crows. They confined themselves to four-wheel-drive vehicles, their forms resembling rolls of black fabric. Black flags waved from the car windows, stark and ominous.

They weren’t from my city. Yet they celebrated the collapse of Raqqa into their hands in 2013, declaring it the capital of their caliphate. They chose our neighbourhood, Al-Firdaws, as their headquarters.

The square that once hosted weddings and funerals—the same square where I celebrated my marriage—was now a place of public floggings and executions. The Euphrates River became a blood-red stream, fed by the throats of Raqqa’s people.

The women in the streets resembled Daesh flags—pieces of black fabric fluttering through Raqqa’s alleys. I couldn’t distinguish my wife from my mother or my sisters unless they entered the house and lifted their veils. Even my father vanished, retreating into the safety of our home, fearing arrest or execution. This fear grew after Daesh seized his butcher shop, taking every sharp tool and piece of equipment, declaring that no one in the city could possess weapons—or anything that could be turned into one.

This was the fate of Raqqa’s people in Syria’s war: masked men cutting off our heads on the ground, while indiscriminate airstrikes rained down on us from the skies—delivered by planes from every corner of the world.

5: The Farewell Ceremony

I was a spectator, watching everything I’ve told you unfold from behind the curtains of my home, as though I weren’t part of the story. But I might have become one of its victims—if I hadn’t fled.

I didn’t know why, but I wished my wife could swallow me whole and make me disappear inside her forever when I heard that Daesh had blinded a man and thrown him off a tall building, his head exploding against the asphalt because he had been accused of sodomy. Feverish thoughts of his fate struck me, confining me to bed for seven days. My wife had no choice but to cover my face with compresses soaked in cold water. Beneath them, I pretended to be dead, terrified of the fever leaving my body and waking up to face her—the same woman who had plucked my eyebrows with her hands, tried caramel wax on my chest to make it smooth, let me test her lipstick in front of her mirror, and allowed me to wear her clothes, even her lingerie and bra. She touched and explored my body wherever I wanted in our bedroom. When I recovered, she startled me by saying:

“You’ve tried everything in my cupboard except the burqa.”

She booked two bus tickets for us to travel by land from Raqqa to Turkey through the Syrian border crossing at Jarabulus. In 2014, the roads were still open. She tossed the tickets into my lap along with a heavy black fabric, saying: “This blackness is a void. Either you fall into it forever or step out of it into the light… for whatever remains of your life. Wear it!”

She laid the burqa on the floor in the shape of a circle and told me to step into the centre. I obeyed. She picked up the edges of the burqa with her fingertips and slowly lifted it, and I felt as though a black tide was rising from the ground to engulf me. She told me to close my eyes as she lowered the black veil over my face. Then she asked me to open them. I opened my eyes, my heart trembling, for I had only hidden behind the fabric out of fear.

My wife laughed and said I’d need to wear a bra to create some feminine curves on my body, but I wouldn’t need women’s shoes—“There isn’t a size 41 women’s shoe in all of Raqqa anyway.” The hem of the burqa was so long it brushed the ground. I added, “And I’ll need to thread my eyebrows and apply kohl to my eyes, just in case they ask me to lift the veil .”

My mother gathered every piece of gold from her collection—bracelets, necklaces, rings, earrings, and even the golden pins I had received at birth. She wrapped them in a cloth and tied it around her waist like a belt under her clothes.

We were ready to do it—until Daesh changed their travel rules that week. They began allowing men to accompany their wives as mahrams on the journey. This news prompted many of Raqqa’s residents, especially the wealthier ones, to leave the city. My father had no choice but to order all of us to leave—me, my wife, my mother, and my sisters.

My mother gathered every piece of gold from her collection—bracelets, necklaces, rings, earrings, and even the golden pins I had received at birth. She wrapped them in a cloth and tied it around her waist like a belt under her clothes.

The microbus was waiting for us in the dirt square behind our house and in front of my old school. It was the same square where we had celebrated so many weddings and funerals. This time, it was hosting our farewell ceremony—our last celebration in that square.

Even today, June 25, 2020, I sit at the seaside café, watching boats in the distance emerge from infinity. I admit and confess: I have no regrets about marrying that woman with lace gloves, no regrets about stealing her lipstick with kisses, no regrets about our laughter or our tears together. She was a remarkable woman, and she always will be. She had a heart that embraced me with my fears and naivety. Without her, my body would never have been freed, nor would I have understood what it means to stand by a woman.

At the same time, I have no regrets about divorcing her. I wanted to free her from my prison, though she refused to leave it until the very last moment. She had fought for my life, and I wanted to fight for her freedom. I believe we both won—because she will come to know the love she deserves, with a man who will make her heart race, or perhaps with a woman. I left her standing tall, like a lighthouse on a Mediterranean shore.

And here I am today, on another shore—safe but distant. I breathe in the seaside air, but my heart aches with longing for the expansiveness of the desert and gusts of nostalgia blow deep within me. Winds that carry me back to rustic celebrations and villages under starry skies.

I watch my past across a continent, rushing towards me across the sea. I take a morning coffee as we always did. But I close the notebooks telling of waves and seashells to begin sketching a new life—a new life for that fierce child with kohl-lined eyes and a chest adorned with golden pins. The child whose birth was celebrated by the heavens.

© Khaled Alesmael 2025