“Catherine Ross, Lady Foulis, thou art accused for the unnatural abusing of thy self, contrary to the laws of God, and exercising and using thy self, most ungodlily and wickedly, by the perversest of Enchantments, Witchcraft, Devilry, Incantations and Sorcery …”

Lockdowns lead to strange reading. I found this Dittay, as an indictment was known in Middle Scots, in Pitcairn’s Ancient Criminal Trials in Scotland. Robert Pitcairn was a Scottish antiquarian and lawyer, and a close friend of Sir Walter Scott’s. Ancient Criminal Trials, published in 1829, is a delicious collection of thousands of pages of original trial documents, letters and state papers, running from the 15th to 17th centuries. As Pitcairn says in his somewhat self-satisfied preface, the task occupied several years of “laborious exertion”, poring over “repulsive materials.” It details crimes of murder, high treason, forgery, arson, poisoning and witchcraft, in a crabby nineteenth century font.

Initially, I was fascinated by the language. One of the earliest entries is titled simply “Slaughter” and records that Thomas Broune was convicted “art and part of the slaughter of umquhile Thomas Achinsoune.” Some rooting around in the Oxford English Dictionary revealed that “art and part” is a Scots law term for aiding and abetting and that “umquhile” means deceased. The strange spelling, unfamiliar words and inordinately complex syntax were catnip to a linguist like me. But as I randomly flicked through the volumes, Lady Foulis’s name leapt out. I remembered it from a passage in Scott’s Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft, where he says she “made use of the artillery of Elfland.” As I read the original trial documents, a story emerged that made Macbeth look tame.

Easter Ross in the Scottish Highlands was home to two great families in the 16th century. The Munros had come from Ireland at the start of the second millennium and gained lands along the Cromarty Firth – an 18-mile stretch of water – where they built Foulis Castle as their fortified home (thanks to AirBnB you can rent rooms in the castle today). Clan Ross came a little later. They had once been Earls of Ross, their lands stretching across the Highlands. Though they lost the Earldom, they remained a power in the region, settled at their castle in Balnagown, about 15 miles north and east of Foulis Castle.

In the second half of the 16th century, Robert Munro, Baron Foulis, remarried. His first wife had died, having borne him two sons and three daughters. His neighbour, Alexander Ross, had a daughter, Catherine. It suited both families to knit their lines together, so much so that the two men had contracted to marry Catherine to Robert should his wife die. Alexander was a violent man who was obsessed by power and took delight in violence. His daughter Catherine, it would turn out, had a similar temperament.

Catherine and Robert were married at Foulis Castle in 1563, and she bore seven children to him, including a son, George. Robert, however, refused to make over to young George lands he had gained since the marriage. This was not what had been contracted, and Catherine was furious.

The year of Catherine and Robert’s marriage was also the year that Scotland’s new Parliament passed an Act which forbade Witchcraft on pain of death. Mary, then Queen of Scots, was Catholic, and at odds with a Protestant Parliament that sought to banish her religion from Scotland. The Act, which inveighed against “vain superstition,” code for Catholicism, was a result of the tussle between Queen and Parliament. At the time, most common people mixed ancient folk-belief and Catholic ideas. Healing wells across the Highlands of Scotland, where people came to cure their illnesses and left rags tied to overhanging trees, were named after Catholic saints. The incantations that the spae-wives, village healers, used to cure cattle, or turn the evil eye, invoked the Trinity. Charms sung by girls collecting herbs called on Saint Brigit, a Christian overlay on Brìghde, Celtic goddess of healing and fertility. In Scotland, those skilled in such magics were called Charmers. The Act sought to stamp out their kind, and the religion they practiced.

Charms, of course, can be turned to good or evil ends, and Easter Ross was famed for sorcerers of both sorts. By 1577, Catherine’s plans to gain land for her son were going nowhere. She concocted a new and more murderous approach. She decided to use evil magic and poison to kill her husband’s eldest son, also called Robert. With him out of the way, the plan was for Catherine’s brother to marry Robert’s widow. This meant that Catherine also needed to murder her brother’s wife, Lady Balnagown. If Catherine was successful, then the Ross family would take over the Munros’ lands and the succession, becoming the Barons of Foulis and the preeminent clan in the territory.

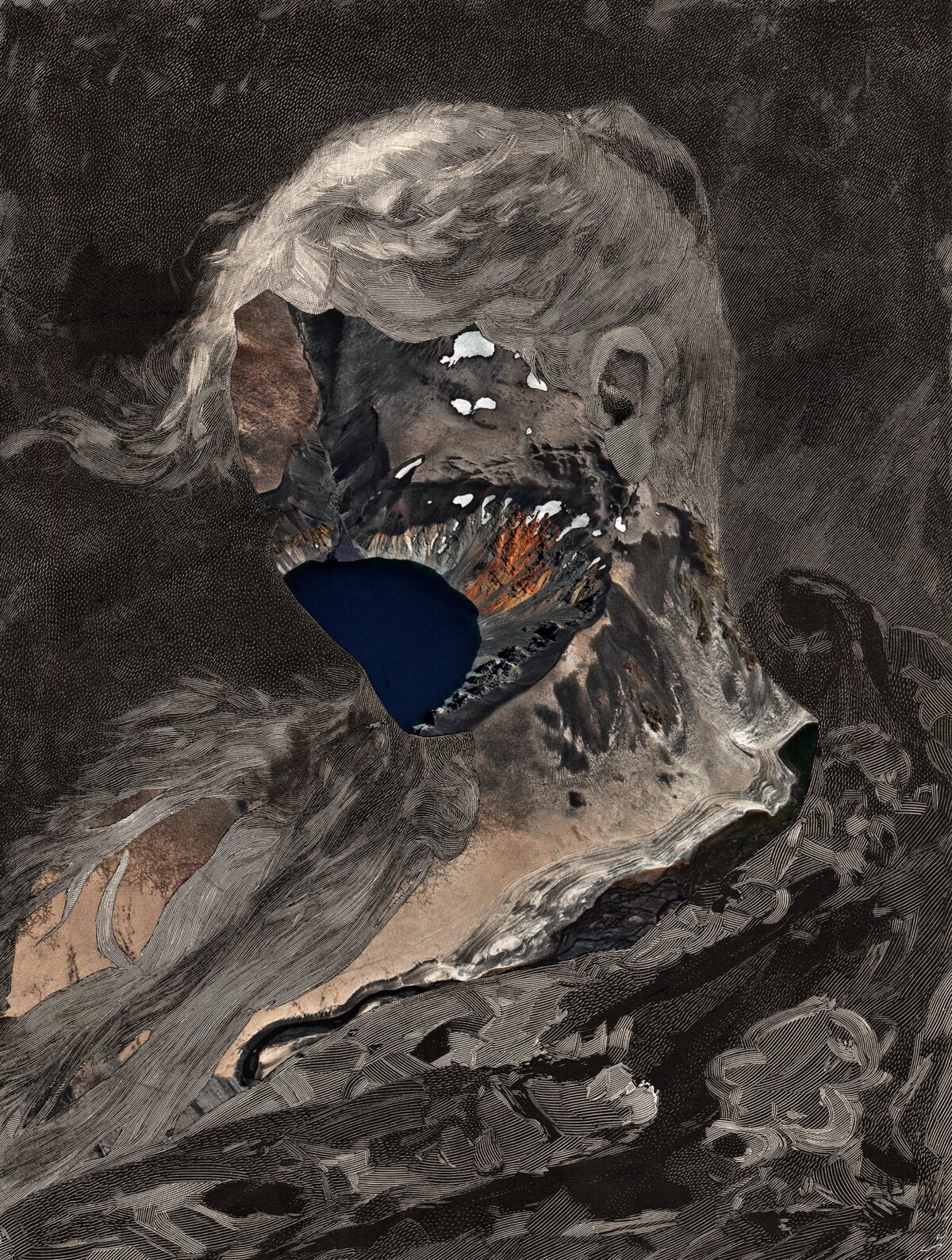

Heedless of the new Witchcraft Act, Catherine consulted with a community of local witches, centred around Tain, the largest town in the district. The accounts of the trials that eventually took place name over 30 witches, many of whom were notorious across the region. One of these was Marion MacAlasdair. Marion’s witchery had little to do with Satan and the Black Mass. It was entwined with belief in the elf-folk, the Daoine Sìth, who haunted the raised mounds that peppered the landscape. In Gaelic legend, the Daoine Sìth shaped deadly elf-bolt arrowheads from black flint that could be used for malevolent purposes, the “artillary of Elfland” that Walter Scott wrote about. You can still find these arrowheads, the remnants of real Neolithic hunts, buried in peat, or nestled among the pebbles of the sea shores of Scotland. I have one myself. For the witches they were instruments of magical death. Marion advised Catherine to go to the raised mounds and consult with the elf-folk.

The witches then created figurines of Robert and of Marjorie, Lady Balnagown, the two who Catherine needed rid of. These figures were cuirp-criadhach, clay corpses. Usually a witch would make a clay-corpse in the likeness of their enemy, and then lay it in running water. As it dissolved, so would the person it resembled waste away. The Tain witches sought a speedier outcome. They used elf-bolts, which they shot at the clay corpses of Robert and Marjorie in an attempt to destroy them, and bring about the deaths they sought, but the young Heir of Foulis and the Lady of Balnagown remained alive. More practical methods were called for, and the witches then brewed poisons that they slipped into ale. Though they failed to kill Robert, Marjorie was rendered an invalid to the end of her short life, and two servants met their deaths by the witches’ poisons.

The conspiracy included so many that it was soon no longer secret, and the young King, James the Sixth, later author of the notorious compendium of witchcraft, Daemonologie, appointed Baron Foulis, Catherine’s husband, to prosecute the witches, and his own wife. Many escaped, but in November and December of 1577, ten people were strangled and burned as witches at the Channonry of Fortrose, south of Easter Ross. More were burned the following year. Catherine fled north to relatives in Caithness.

Eleven years later, Catherine’s husband died. His eldest son, who had been the victim of Catherine’s malefice, was now Baron Foulis and set up a jury to try his stepmother. He mysteriously died before the trial began, and it was Hector, the second son, who brought the prosecution. In a strange twist, Hector himself was also accused of witchcraft. He had become ill after his brother’s death, and was terrified that his stepmother had cursed him. Hector employed three witches to turn the curse away from him, and onto Catherine’s eldest son in his stead. A bizarre ceremony took place: the witches buried Hector alive, and stood around him while he lay in the earth. Then one of the witches ran across nine fields and on returning asked the chief witch who should die, Hector or his step-brother, Catherine’s son. Once the question was answered, Hector was disinterred. The spell seems to have worked. Hector recovered from his illness, but Catherine’s son died soon after.

The trials of both Catherine and Hector took place in July 1590, on the same day. The Munro family had the power to appoint who they wished as jurors in Witchcraft trials. The juries were accordingly packed with tenants of their estates, and both were acquitted, with all charges dropped. As they walked free, at least 13 people had been strangled and burned as witches, and two of Catherine’s servants had died at her hand. Hector went on to run his estates, and Catherine lived a long life. Sometimes those in power play their games, make their gains and slip free of the destruction they leave behind.