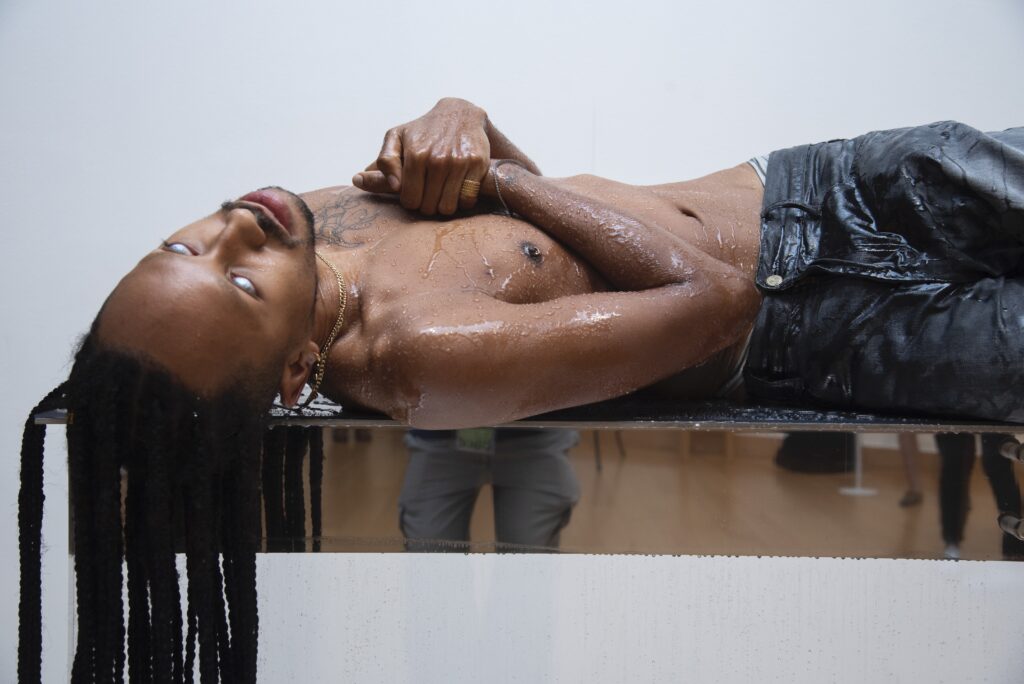

In fairy tales, people are turned into inanimate objects against their will, magicked into statues, or put to sleep for a hundred years, until set free by a prince’s kiss. The performance artist and sculptor Miles Greenberg wills himself into states of suspended time, feats of endurance that test his body, pushing against his physical and mental limitations. As time passes his body may begin to buckle under the strain, a living sculpture that invites us to contemplate vulnerability, suffering, objectification, desire. A recent piece, “Étude Pour Sébastien,” involved piercing his body with arrows, and then posing for five hours in the Louvre’s spectacular Cour Marly, filled with 17th and 18th century sculptures, his Black body a striking counterpart to the white marble figures around him. For “The Embrace” (2020) at Copenhagen’s Enter Art Fair, he sat on a rock, Little Mermaid-like, in a glass cube embracing his collaborator, Sall Lam Torro, for 21 hours. For “ Oysterknife,” also from 2020, he walked on a conveyor belt for 24 hours without pause, an homage in part to the pioneering performance artist Senga Nengudi, a lodestar for Greenberg. Another influence and friend is Marina Abramovic´. Like her, he has turned his body into a canvas for his art, synthesizing sculpture and theater in performances that feel as if they have no particular beginning and no end. Here Greenberg and the writer and model Amber Later reflect on video games, fighting through pain, and Saint Sebastian as the original twink.

Miles Greenberg: Hello Amber. We are sitting here on my living room floor sipping tea. You live across the street. How are you feeling?

Amber Later: I’m feeling very calm. I’ve been in a pretty focused state for the past couple weeks. What about you?

MG: I’m taking the time to get re-embodied, because I’d been feeling a little a little dissociative. When I put out a big piece of work, or when I’m making a new piece of work, I’ll find myself feeling slightly outside of myself. Once I’ve put enough of myself into a piece of work and it finishes, it’s sort of like I leave my consciousness behind in the gallery.

AL: Writing is like a composite of all of my thoughts and feelings over a long period of time. Anything that crosses my mind, or how my mood is on any particular day can influence the piece and the next day it’s something else. To be done with a work is to kind of discard sometimes months of affect.

MG: It is always interesting for me to talk to people who work on things for months and years on end. My impulse towards performance was always about immediacy. When I make something, I’m just naturally prone to wanting to light it on fire and throw it away after. And performance is perfect for that because you get an instant response to what you produce from your own body, from the bodies of your audience. And when it’s over, it’s over. You don’t get strapped with the responsibility of having to decide when it’s finished, it just has to end, eventually. You’re constrained by time and your own physical limitations. When you’re writing, or making music, or painting—it could all go on forever.

AL: Which is interesting to me because I feel like a major theme of so much of your work is duration, and an interest in transformation over time.

MG: Do you find that, over time, when you’re spending months or years writing something, that you transform with it?

AL: Yes, absolutely. Especially with writing. If I’m trying to write to capture a very particular perspective on the world, or a character’s subjectivity, even if it’s a fictional character, by forcing myself to think about it, and really entrench myself in it, it can definitely affect how I orient my thoughts outside of the writing practice too. I think when I’m finished with something, a lot of times it feels almost a little alien to me, in the same way that I think past selves often feel a little alien. Trying to remember how we were at a particular time or why something particular mattered to us when the situation or circumstances of our life are different.

MG: It is always interesting for me to talk to people who work on things for months and years on end. My impulse towards performance was always about immediacy. When I make something, I’m just naturally prone to wanting to light it on fire and throw it away after. And performance is perfect for that because you get an instant response to what you produce from your own body, from the bodies of your audience. And when it’s over, it’s over. You don’t get strapped with the responsibility of having to decide when it’s finished, it just has to end, eventually. You’re constrained by time and your own physical limitations. When you’re writing, or making music, or painting—it could all go on forever.

AL: Which is interesting to me because I feel like a major theme of so much of your work is duration, and an interest in transformation over time.

MG: Do you find that, over time, when you’re spending months or years writing something, that you transform with it?

AL: Yes, absolutely. Especially with writing. If I’m trying to write to capture a very particular perspective on the world, or a character’s subjectivity, even if it’s a fictional character, by forcing myself to think about it, and really entrench myself in it, it can definitely affect how I orient my thoughts outside of the writing practice too. I think when I’m finished with something, a lot of times it feels almost a little alien to me, in the same way that I think past selves often feel a little alien. Trying to remember how we were at a particular time or why something particular mattered to us when the situation or circumstances of our life are different.

MG: Sometimes when I finish a performance, there’s this very automatic reaction that occurs. It leaves me with that disembodied feeling that I was talking about. And it’s this unconscious severance of an umbilical cord between an idea and me after I’ve given birth to it and it leaves my body, the scars heal, the fatigue subsides, and I’m rested and there’s no longer a solid trace of it inside of me, just a shadow. I definitely feel like I have to cut a psychic thread between myself and the thing, but I think I lose a little blood with it every time.

AL: Well, also your work is so much more physically intense than mine. Writing, especially fiction, takes me to such an abstract, immaterial place. Sensuality in fiction is extremely important to me. I do think good fiction should try to appeal to different senses, because so much of people’s emotions and memory are stored there, but at the same time, it’s all quite abstract or illusory when I’m writing. So when I finish, it’s almost coming up for air, being able to breathe again, touching things and looking at things, and being present in a material world and feeling back to myself. So, many times, I feel a little more grounded after I finish something. And I think that has to do with just the abstract nature of it.

MG: I think that I go into that really abstract place that you’re talking about when I’m conceiving of a work and what it looks like to me because, at that stage, it feels like a poem. When I’m structuring a performance, I’m thinking firstly about how the audience’s bodies are moving in the space, and how they’re going to be physically affected. I’m not really taking into account what my own body is going to do, and I try not to think too much about what it’s going to do to me. I would rather find out in the moment. I don’t ever know whether I’m physically capable of doing something and I never think about it until I’m in the midst of it. And so there’s a certain, I guess, leap into the void…

AL: When you’re in the middle of a performance?

MG: Well, yes. But even before, when I’m going into it, like when I decided that in “Oysterknife,” I was going to walk for 24 hours, I was coming at that from a completely abstract, poetic place. And then I enacted it literally with my body—I trained ahead of time to make sure that I could do something, but I didn’t necessarily know if I could do it. Does that make sense? There’s no such thing as rehearsal for me.

AL: I have a very similar leap of faith experience with writing at the beginning where I have to will myself to believe in a world that doesn’t exist yet because I haven’t created it. But I find to convince an audience, to convince a reader, I have to believe in it. I have to believe in something as I invent it. And before the story is written or before the novel is written, I have to trust that there is this world that I’m going to create or discover before I fully know what it is.

MG: Did you ever play video games as a kid?

A lot of times in my adult life, I try to search for that feeling of these wide, expansive landscapes, these endless stories and scenarios and characters that excited me as a kid. And what I realized was what I liked about video games was the fuel they gave to my imagination.

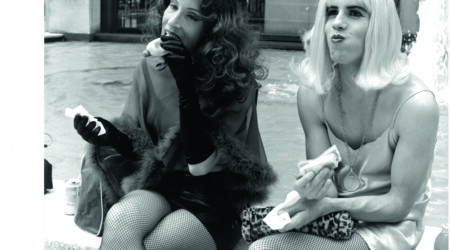

amber later

AL: Yeah. I was thinking about video games the other night because a lot of times in my adult life, I try to search for that feeling of these wide, expansive landscapes, these endless stories and scenarios and characters that excited me as a kid. And what I realized was what I liked about video games was the fuel they gave to my imagination, what they gave me to daydream about when I wasn’t playing. So I liked a lot of fantasy, a lot of role-playing games.

MG: Do you still play any?

AL: I tried playing a Final Fantasy game recently, but I found a lot of the emotional beats of the storytelling pretty clumsy. What I’m most interested in recently is this idea of world building. I think, in literature, in the past there have been a lot of established worlds that artists would go into. Either drawing on folktales or, like in much of Europe, for example, a very specific Christian cosmology with the relations between heaven and hell, or between angels and humans, that artists could go into and fill with their own narratives and twists or interpretations. But there was a certain established logic and system that a lot of people across the culture already understood. And now we’re sort of in an era where, it often seems to me, it’s kind of up to every artist to invent their own world, and what distinguishes an artist is how completely they’re able to envision a world inside themselves and communicate that.

MG: I feel the same, and the same way that I was obsessed with video games as a kid, that obsession has transferred over to my work. What are your thoughts on obsession?

AL: Obsession is really necessary for literature because it’s ultimately inventing patterns that aren’t really there, sort of the way we make constellations, drawing lines between isolated points. I recently read a Romanian novel called Solenoid [by Mircea Cărtărescu, translated into English by Sean Cotter]. It’s a bit surreal, it’s very hard, as a reader, to distinguish what is an internal experience of the narrator’s, what’s an external experience, what is a dream or hallucination or fantasy versus what’s actually happening, or if that distinction really matters. I had to put it down about halfway through for a few weeks though, because this character is so deeply obsessed with his own medical anxieties, with a lot of things related to hygiene and the functioning of his body. And it seems like on every page, the only way that he can orient himself in relation to the world is through the lens of bacteria, vaccinations, body modifications, his skin… And I started to see the world that way too, while reading.

MG: Yeah. I think what you’re immersing yourself in definitely affects how you feel in your skin. Growing up, I was heavily into Skyrim, World of Warcraft, those kinds of role-playing games. They allowed me to, very meticulously, construct and reconstruct my body…

AL: Creating avatars.

MG: Yeah, exactly. The avatar creation phase of any video game for me was the most important part of the whole game. It was crucial that I was inhabiting a body that was exactly in line with how I felt and what I wanted to feel. And I wouldn’t necessarily wear the strongest armor, but I would wear the one that made me feel correct. Each of my characters became a piece of me, and in leveling them up, it was like I was nurturing a different part of who I was. I was a rogue, a warrior, a priest, a warlock. I felt very attached to these different personas. I have obsessive compulsive disorder, so it was a very holistic way of projecting my body into something that maybe I had a little bit more agency over and could control a bit more acutely.

AL: So when you’re deciding how to present your body in a particular performance, do you feel like it’s a similar process for you now?

MG: Absolutely. My World of Warcraft roster and classical sculpture are two of my biggest references.

AL: And how much of your personhood do you still feel is contained within your body and how it appears to the world?

MG: Good question. A lot of it… I feel like my personhood is something that is almost entirely physical a lot of the time. And to have agency over it through art, and to be able to abstract it and deconstruct it and change it and attribute meaning to it and strip other meanings away from it, I think is something that’s deeply, deeply therapeutic. Now I’ll flip the question to you.

AL: I mean, I have a body, I’m aware I have a body, and especially being trans and transitioning, I have a lot of questions about why my body is exactly the way it is and why I have certain desires for it to be different. So this tension, again, between the body we have and then the different avatars, the different presences that we imagine, is something that I’m trying to understand in my work gradually. I’m also always interested, especially as it relates to issues around identity and being trans, in demystifying these concepts somewhat. I like to push back against the idea that anything I’m experiencing is so singular or so difficult to grasp that there can’t be any point of relation for other people. I personally have a lot of medical anxiety related to things like hormone therapy. For example, on one hand valuing the effects and valuing the very visible way I’ve seen it transform my feeling, my body, etc. But also having issues with medical bureaucracies and the pharmaceutical-industrial complex. Not being an endocrinologist myself, my lack of total understanding of what’s happening biologically can be a point of stress in my life. In this novel, Solenoid, there were passages where everyone at the school that he’s in has to get vaccinated, but they only have one needle. So everyone has to get vaccinated with the same needle. Or he gets lice and has to wash his hair with kerosene because he doesn’t have the right sort of shampoo. And it made me feel better about what was happening in my own body [laughs].

MG: Nothing like kerosene shampoo to put things into perspective.

AL: There are a lot of questions that you don’t ask yourself until you find your body compromised in some way. “Compromised” meaning “made vulnerable,” not “corrupted.” And that can be because of queerness or gender, it can be because of things like poverty and not having access to certain medical necessities. But some people go much of their life without really having any aspect of their physical presence compromised in such an acute way, and it leaves a huge blind spot in their understanding of how the world works.

I don’t know if you’ve ever been stabbed before, and I don’t recommend it, but let me tell you, I didn’t know adrenaline until I had a silver arrow driven through my pec.

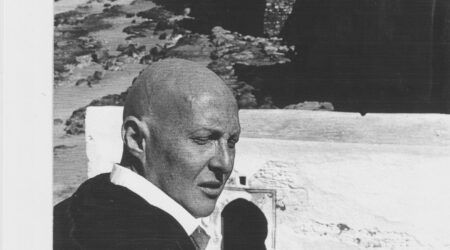

Miles Greenberg

MG: Totally. I can relate it to the sensation of hyper-awareness of one’s body that comes with being Black. That’s very much at the center of my physical experience as a Black person—being repeatedly thrust into my body at random moments. Speaking of the endocrine system, I recently had a very intense encounter with adrenaline. I did this performance at the Louvre. It’s a piece based on St. Sebastian. These classical, iconic museums are filled with the great masters regurgitating the same stories, the same characters, the Virgin Mary, the saints, all of Greco-Roman mythology and deities over and over and over again. Botticelli and Bernini and Caravaggio and Delacroix, they all have their Mary’s, their Venuses, their Echos and Narcissuses. I wanted to put my work in that tradition, so I’m interpreting Saint Sebastian. I performed for five hours as him in the Cours Marly with these large silver arrows pierced through my actual skin. I don’t know if you’ve ever been stabbed before, and I don’t recommend it, but let me tell you, I didn’t know adrenaline until I had a silver arrow driven through my pec. It was one of the most physically intense short-term experience I’ve ever had.

AL: You stabbed them live?

MG: Yeah. I had an expert helping me to thread it under my skin safely. It took a surprising amount of force! And when there’s large a sharp object going through your skin, your body just automatically figures that there’s a good chance you’re about to die. So, your vision starts to go dark. Everything kind of vanishes and gets fuzzy. And your ears… it’s like somebody’s cupping your ears and you lose your hearing for a few seconds. It’s deeply painful but also quite peaceful because suddenly, as you start producing a cold sweat, you’re just sheltered in this self-induced autonomic sensory deprivation. And then a minute or two passes, and as your body realizes that you’re not about to croak, you come back at 110%. Then you’re suddenly completely aware of every cell of your body.

AL: While you were talking, I was trying to think about why it might be that St. Sebastian appeals to so many queer people. And I think it might have something to do with that sense of a betrayed ideal body where you have a very beautiful youth who’s then bound, who’s pierced. So, you have this tension of this ideal, very strong, beautiful, young, sometimes androgynous, maybe masculine-leaning androgynous figure.

MG: Oh, but he’s a total twink.

AL: Twink is really a third gender category.

MG: You heard it here first.

AL: So, you have this twink, and he’s usually depicted so strong and confident, fresh-faced, but he’s in such a compromised position. And I think queer people’s attachment to this image may be related to a sort of cynicism about idealism and the human body.

MG: I mean and there’s also the penetration aspect. Also, his story is that he came out… but as Catholic, which is why he was shot with arrows.

AL: The revelation of a secret identity.

MG: I find that when you look at his gaze, he is always somewhere between… It’s never total agony—it’s pain, but it’s also ecstasy, as in the Greek ekstasis, as in ‘existing outside of oneself.’ He’s always very much at the threshold of very in and very out of his body at the same time, very transcendental in his gaze. In all of the depictions of him, I’m always really drawn to the way that he’s just completely, to be so devoted to an idea that you—

AL: —You’re willing to die for it, or…?

I think Sebastian knows something about pain as a doorway, that pain doesn’t keep increasing exponentially into infinity. It plateaus at a certain point, and we don’t really know what lies beyond the reflex to recoil from it.

miles greenberg

MG: Not necessarily, but that you’re willing to sit with discomfort until you discover what lies on the other end of it, not fearing the horror. I think Sebastian knows something about pain as a doorway, that pain doesn’t keep increasing exponentially into infinity. It plateaus at a certain point, and we don’t really know what lies beyond the reflex to recoil from it. We don’t know what happens when you sit with these extreme sensations for 12 or 24 hours typically in daily life. So I’m very curious about what he knows.

AL: There’s a maxim I abide by in writing that as soon as you touch on something that makes you uncomfortable or elicits some kind of feeling of pain or shame, you have to fight through it. With emotions, I find that sentimentality and overly romantic notions often cloud the truth of a situation.

MG: Okay, my last question. So, Amber, you’re modeling.

AL: Yes.

MG: And I’m making sculptures of my body and videos, and we’re both documenting ourselves at a certain point in our lives and in our timelines that is very crucial, the mid-twenties, which, for many people, is an ideal unto itself. I’m curious about how you feel about, given what we’ve discussed with regards to the many transitions in and of your life, how you feel about immortalizing a moment? How you feel about making your image, and by extension, your body, stand still?

AL: It appeals to me a lot, actually! I noticed this when I started modeling. I already, in many ways, felt alienated from my appearance and kind of dissociated from it, so it wasn’t difficult for me to see it used to serve other people’s imaginations. I think one difficulty that some people might have with the idea of modeling is you’re forced to present yourself in a way that might be totally perpendicular to how you actually want to be seen or how you actually exist. Whereas for me, I just thought, Well, I don’t really care so much. I was so interested in seeing myself in a broken mirror where it’s all these different shards, different reflections from different angles. Because I could see, “Oh, it could be this way one day, it could be this way another day, but I’m still the same person.”

MG: So when you look at images of yourself, do you feel like it’s you?

AL: I think, yes, it must be, on a literal level. I see it as me, but not all of me. The reason I like fiction as opposed to non-fiction is because with non-fiction I have to decide, Well, this is my opinion about this issue, or, This is my perspective, and then commit to it. I have to try to convince my reader of something or at least stand by what I’m saying. Whereas a lot of times I feel a lot more conflicted about who I am or what I want or what I’m supposed to be doing or about things that I observe in the world. In fiction, I can refract myself. I can say, “Well, I’m thinking about this issue and I have three different voices in my head all telling me different things.” So then in the book, I make three different characters and they can all fight with each other and there doesn’t have to be any resolution. And that feels truer to my actual experience. And I think it works the same way visually, I don’t think I have a physical presence that is necessarily the most true version of myself. There are physical avatars that I feel more comfortable with in different situations and are different moments in time but it’s all contextual. And to allow so much capaciousness for the different ways that my body could exist, which also allows me to be a little more open and patient with the process of transformation and knowing that things are always different and always changing. How do you feel about this?

MG: I don’t really think of my performer’s body separate from mine in many ways, either. Sometimes I happen to be them and sometimes I don’t… or rather, sometimes I happen to be in them and sometimes I’m not. And I think making sculptures with my body has taught me a lot about myself. Documenting myself isn’t a primary concern of mine in any way, but it’s been an interesting byproduct.

AL: A final thought. I think it’s very fitting that we use the verb “shoot,” for a camera, that a photographer will say, “I shot someone.” But I think it works as a double entendre because essentially you are killing yourself as you exist at that moment. You are taking that photo in that specific second in time. You shoot it and then it’s frozen, it stops, it ceases to be. Every photograph is a eulogy.

MG: Wow, yeah. I think my sculpture practice and my video practice are really analogous in that way, as well, in that they are about this act of trying to…maybe not really freeze a moment so much as to digest it and extract the vitamins. I think of it almost like a moon lander extracting a sample of some kind of dust or rock or something from a planet and then taking it back and being able to examine it more thoroughly. It’s like a fragment or a very poorly rendered shrapnel. Maybe a fossil. And then having the legible body in that.

AL: It’s a way to inspire self-examination, like you said, the shrapnel, finding a foreign artifact and then using it to try and understand the larger context. I think re-examining my past work is its own kind of psychoanalysis, trying to understand what I meant at the time of writing or what I felt because I have the artifact, I have that fossil of it but I don’t have the feeling that I had in that moment. That’s ineffable, that’s outside of the language.

MG: Sometimes, when I’m looking back on documentation that has my body in it, it feels as though I’m kind of discovering myself clearer in the third person than I do in the first person. I don’t know if that’s something that’s ever happened to you with photographs. I feel like I get to discover myself as though I were a stranger, which sometimes I have a closer relationship to than I do to myself.

AL: Yeah, absolutely. And that’s actually the whole premise of fiction for me. It’s examining myself, not by writing about myself, but by, in fact, writing about these invented characters or personages or scenarios that aren’t a feature of my own lived experience or memory. By outsourcing it in a way, I can see myself more clearly.

MG: Yeah. It’s like you don’t just write fiction, you practice fiction, because you kind of are fiction.

AL: I think that hits the nail on the head.

MG: Maybe we’ve both just been talking to ourselves completely separately in rooms, alone.

AL: That’s why I like the reality body idea. I’m talking to you but I’m also talking to myself.

MG: That’s probably why we’re friends. Amber Later, thank you so much for being fictitious with me.