In the American South, along a 200-mile stretch of the coast of South Carolina and Georgia, there is a scar on the Earth’s surface so big it can be seen from outer space. Starting in the seventeenth century, more than 40,000 acres of land were cleared here and 780 miles of canals dug, all to produce food. This is just one mind-jolting legacy of centuries of punishing labour by enslaved people. Most motorists who travel along this part of the Lowcountry are probably unaware that what they’re passing is as close as anything America has to a Great Wall of China or the Great Pyramids of Giza.

This land was cleared for rice, which grew in abundance in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, traded mostly through the nearby city of Charleston, then home to many of America’s wealthiest farmers. Carolina Gold rice was shipped around the world. English importers described it as being the weightiest, largest and whitest rice in the habitable world, with a taste of hazelnut and a luxurious melting wholesomeness. It commanded extraordinary prices in the markets of Paris. After ripening in the Southern sun, ready for harvest, it was said to take on the lustre of an antique wedding ring. This glorious rice had a companion, a far humbler food, a tiny pea. This legume not only helped to nourish the soil on which the rice grew, but it also fed the enslaved people who laboured in the rice fields. All three – the people, the rice and the pea – came from Africa.

Between 1619 and 1860, 12.5 million enslaved Africans were trans ported along the Mid-Atlantic Passage to the Caribbean and the Americas. Ten and a half million survived the 4,000-mile journey and were put to work on prairies and plantations to grow tobacco, corn, sugar, cotton and rice. Most were taken from West Africa, from Senegal down to the Ivory Coast. Seeds travelled with them. Some stories suggest that the seeds – tiny enough to be hidden but important enough to risk being smuggled – were brought by the Africans themselves, concealed in their hair. A seed could be a life-saving resource on a journey into the unknown, the theory goes. Others argue that if seeds made it on board a slave ship, they would have been placed inside a hold, bounty collected by botanists and seen as potential crops for the New World and a food source for the enslaved.

‘Slave traders understood that good labour depended on good health,’ says the food historian Jessica Harris, and so they stocked up on supplies of cowpeas and rice at West African ports, knowing the enslaved people were more likely to accept them than other foods. ‘Refusing to eat was the only control the Africans had left,’ says Harris. ‘It is generally believed that the slaves do best with the food of their own country,’ said a close observer of the trade, a botanist called Anthony Pantaleo who travelled to Ghana in the 1780s for the British government to identify useful crops, ‘every slave ship takes out a large quantity of beans as food for the slaves.’ Alexander Falconbridge, a surgeon who travelled on four slave voyages, told a committee of MPs in 1785, ‘The negroes were fed with beans and rice,’ adding that the quantities of food provided were ‘barely sufficient to support nature.’

Slave ships carried Africans to the Americas not only to put them to work on the land but also for their agricultural skills. The farming knowledge of the enslaved, and the food it produced in the New World, including rice and sugar, helped make the industrialization of the world possible. Culinary historian Michael Twitty has made the case that white owners paid a premium for men and women from regions in West Africa where rice and peas grew. Before the invention of chemical fertilizer, knowing which pea or bean to plant where and when meant the difference between farming success and failure. The people brought from West Africa knew this.

The 4,000-year-old charred remains of a pea, Vigna unguiculata, have been found in rock shelters in Ghana, surrounded by fragments of pearl millet and oil palm. The pea was a food of the savannah, a plant adapted to life in the marginal dry and hot places where most other crops failed. Its value wasn’t only in its high-protein seeds, but also in its bushy edible leaves, rich in vitamins and beta-carotene. Still today, in the region radiating out from that cave, millions of West Africans depend on this tiny pea species for nutrients for themselves as well as to feed the soil. Traditionally farmers intercropped them with cereals, including indigenous varieties of rice, so to European and American farmers these legumes became known as ‘field peas.’ Because they were fed to livestock too, the name ‘cowpea’ stuck.

In the parts of the New World where enslaved Africans were sent, you can find cowpeas served with rice: in Brazil, baiao de dois; in Puerto Rico, arroz con gandules; in the Caribbean, moro de guandules; and in the American South, Hoppin’ John. Every community that grew peas would have had their own prized landrace varieties (30,000 different samples of cowpea are held in seed banks around the world, most about half a centimetre long, and they come in a kaleidoscope of colours, from earthy browns to vibrant pur ples).

After cowpeas arrived in the American South and were taken up by plant breeders, the legumes became essential ingredients in farming and food. Their various names hint at their different uses. The no-nonsense-sounding iron pea and clay pea were soil improvers while the more refined lady pea was, according to a nineteenth-century plant breeder, J.V Jones, ‘a delicious table pea.’ Black-eyed peas, Jones claimed, were so chalky they were ‘more valuable for stock making.’ Lists of these Lowcountry peas go on and on. People grew to know their late locust from a flint crowder, and a relief from a shinney (the prince of peas, according to Jones).

‘If you were poor you would have had a breakfast of rice and peas,’ explains heritage grain expert Glenn Roberts, recalling a saying from his childhood in the South, ‘and then when you came home after working in the fields, you had a brand-new meal: peas and rice.’

By the 1830s, rice, corn and cotton had been cultivated so intensely that Southern soils had become exhausted. An agricultural crisis loomed, and experts called for a concerted effort to rebuild the soil before it became so depleted that economic collapse would be inevitable. The solution was to plant more cowpeas and practice crop rotation; with their nitrogen-fixing powers, peas put back the fertility lost from intensive farming. And so, African peas combined with rice grown in the Carolinas became the cornerstone of Southern cooking and continues to be so to the present day. Rice and peas cut across all barriers, social, economic and racial. ‘If you were poor you would have had a breakfast of rice and peas,’ explains heritage grain expert Glenn Roberts, recalling a saying from his childhood in the South, ‘and then when you came home after working in the fields, you had a brand-new meal: peas and rice.’

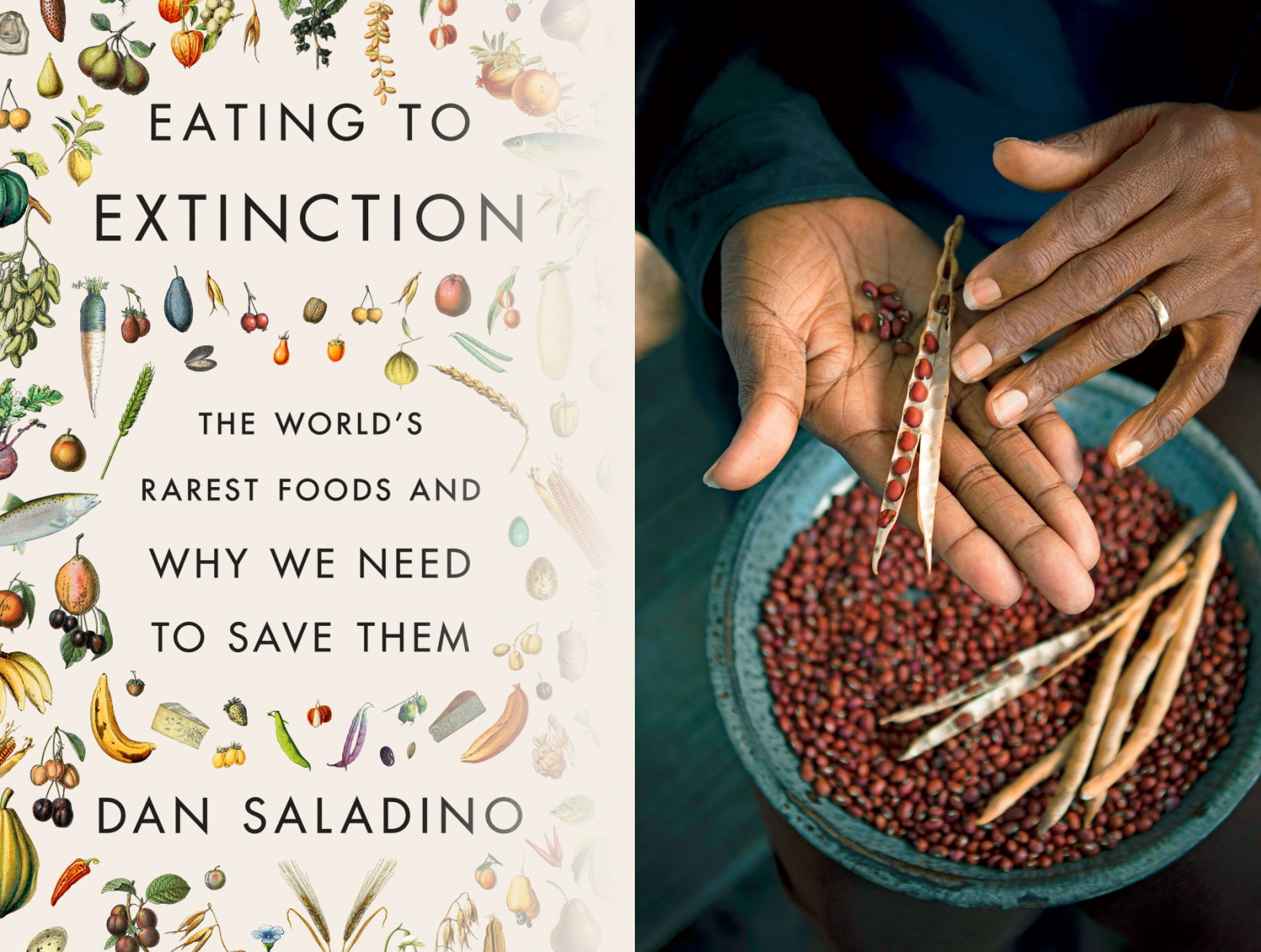

While rice farming was booming in the nineteenth century, some rarer landrace peas were cultivated by enslaved Africans in secret gardens which contained forbidden food, such as varieties of African red rice, beloved by the enslaved but deemed a threat by slave owners who saw them as a potential contaminant of their fields of lucrative white rice. In these gardens, Africans also grew varieties of sweet potato, benne (sesame), kale, okra, collards, watermelon and sorghum, which had all somehow found their way from Africa into the American Lowcountry. Always in these secret gardens, without exception, were cowpeas. But there were parts of the South where the enslaved didn’t need to hide their crops away. On an isolated Sea Island off the coast of Georgia called Sapelo, Africans had more freedom and were allowed to grow their own crops. There, unique landrace plants evolved, including sugar cane and citrus, but perhaps the most remarkable of all a tiny, red-brick-coloured pea.

Seen from a map, the south-eastern coast of the USA looks as if it’s crumbling away into small pieces. Here, splinters of land, around a hundred in total, form a chain of islands. Over thousands of years they have been home to different cultures: indigenous Native Americans; French colonists; American plantation owners; and enslaved Africans, followed by their freed descendants. Three hundred years ago, some of these Sea Islands were points of arrival and of quarantine for slave ships from Africa. Some of the enslaved men and women stayed on these islands which, surrounded by swamp and marshland, were rich breeding grounds for insects and disease. The harsh conditions and relative isolation of the Sea Islands perhaps explain why the Africans here had more autonomy over their food than enslaved people in other parts of the South. The tiny red cowpea they grew became an essential ingredient for people forced to work from sunrise to sunset. The pea was cooked long and slow in cast-iron pots and turned into a gravy which was served up with local rice. Constant cooking of this gravy, day after day, year after year, stained red rings onto the insides of metal pots (markings that can still be seen on now antique plantation cookware).

The descendants of the enslaved Africans of Sapelo (as well as other Sea Islands and parts of the Lowcountry), describe themselves as Geechee. It’s likely the name is derived from the Kissi (pronounced Geezee) tribe in West Africa. Sapelo is still remote; unlike neighboring islands with bridges to the mainland, you can only get there by boat or aircraft. This is why the community has retained uniquely strong links to its West African roots. The way some people on Sapelo speak, how they cook and the way they dance have closer cultural connections to Sierra Leone, Ghana and Senegal than to African American culture on the US mainland.

The Geechee of Sapelo were among the first freed slaves to purchase land and set up autonomous communities. This led to the preservation of African foodways and farming practices, including the planting of the Geechee red pea which has continued to this day. The survival of that pea in recent years is thanks in part to one woman, Cornelia Walker Bailey.

Her family had always grown the red peas, and for much of her life Bailey thought nothing of it. She and her husband Frank sowed the seeds early in spring (to a growing moon, she said) and harvested them during the summer. Her life seemed to run to the rhythm of the pea, from the saving of its seed in the autumn, to the big get-togethers when the islanders would cook up pots of red pea gravy and rice, a must on New Year’s Day. The pea carried a lot of history, and pain, but it also spoke of being Geechee.

Bailey began to see the red pea as a means of saving Geechee culture. People who left the island always asked to be sent supplies, and it grew so easily on Sapelo, maybe it could generate an income and so help Hog Hammock remain a place for Geechee people.

In the last few decades, things around Sapelo have changed quickly. In the 1950s, developers began to buy up land on the other Sea Islands, attracted by their pristine white beaches and dense forests. Then interest turned to Sapelo. As plot after plot on the island was bought up by outsiders, the last of the Geechee retreated to Hog Hammock, a part of Sapelo that became something of a refuge. But even here house sales to the wealthy sent property taxes higher, pushing the African descendants out. In 1910, five hundred Geechee people lived in Hog Hammock, by 2020 there were no more than forty. As their numbers kept dropping, Bailey feared for the survival of her people. Cultural genocide she called it.

Bailey began to see the red pea as a means of saving Geechee culture. People who left the island always asked to be sent supplies, and it grew so easily on Sapelo, maybe it could generate an income and so help Hog Hammock remain a place for Geechee people. In 2012 Bailey began planting the crop, helped by her sons, Maurice and Stanley. It was touch and go; supplies of the seed were so low that one summer when a drought hit the island, they had to go door to door asking people if they had some red peas stored away for safekeeping. But the crop started to grow, and word spread to African American farmers interested in finding out more about their food history.

One of these was Matthew Raiford, a farmer on the mainland. His great-great-great-grandfather Jupiter Gilliard was born into slavery in 1812 in South Carolina and became a landowner in 1874, buying 476 acres of farmland for $9 and taxes in Brunswick, Georgia, just north of Sapelo. As a young man, Raiford wanted nothing to do with the South and most definitely not its soil. In the years after the civil rights era, the message had been loud and clear: ‘Don’t be a farmer, become a doctor or a lawyer instead,’ he says. Farming was tough and, for some, working on the land was too bound up with the history of slavery. In 1910, African Americans made up about 14 per cent of America’s farmers; today that figure is less than 2 per cent.

Raiford joined the military and then worked as a chef, but in the 1990s his grandmother persuaded him to return to the family farm. One day, he came across the story of Cornelia Bailey. He remembered his grandparents had grown a red pea and so he made the journey to Sapelo Island to meet ‘Miss Bailey’. Walking onto the island was like going back in time, he says. People spoke in Geechee dialect and used expressions his grandmother used, like the midday sun feeling ‘hotter than fish grease.’ Bailey was working a hoe on an acre of peas when he found her. ‘And I’m looking at her thinking, is it really that easy?’ he says. ‘Baby, this pea don’t need no fuss,’ she told him, ‘the pea knows what it wants to do, all you’ve got to do is break the soil, drop in a pea, cover it and give it some water, it’ll grow.’ She was right. The plant is tough, and it now grows on Raiford’s family farm near Brunswick.

Someone else who came from the mainland to help bring back Sapelo’s red pea was Nik Heynen, a professor of geography at the University of Georgia who was converted to farming by Cornelia Bailey, ‘one of the most important people in my life.’ When Bailey died in 2017, still hoping the pea was going to save Geechee culture, Heynen worked with her children to keep the crop growing. ‘If we lose the pea, we lose a variety of something that helps us understand the world,’ he says. The pea tastes different to anything else, not a thousand times better than anything else, just different, and because he helps to grow it on Sapelo, for him the pea comes from an emotional landscape as much as a physical one. ‘The tiny red pea is infused with so much history and culture,’ Heynen says. Which is why he can’t imagine letting it go extinct.

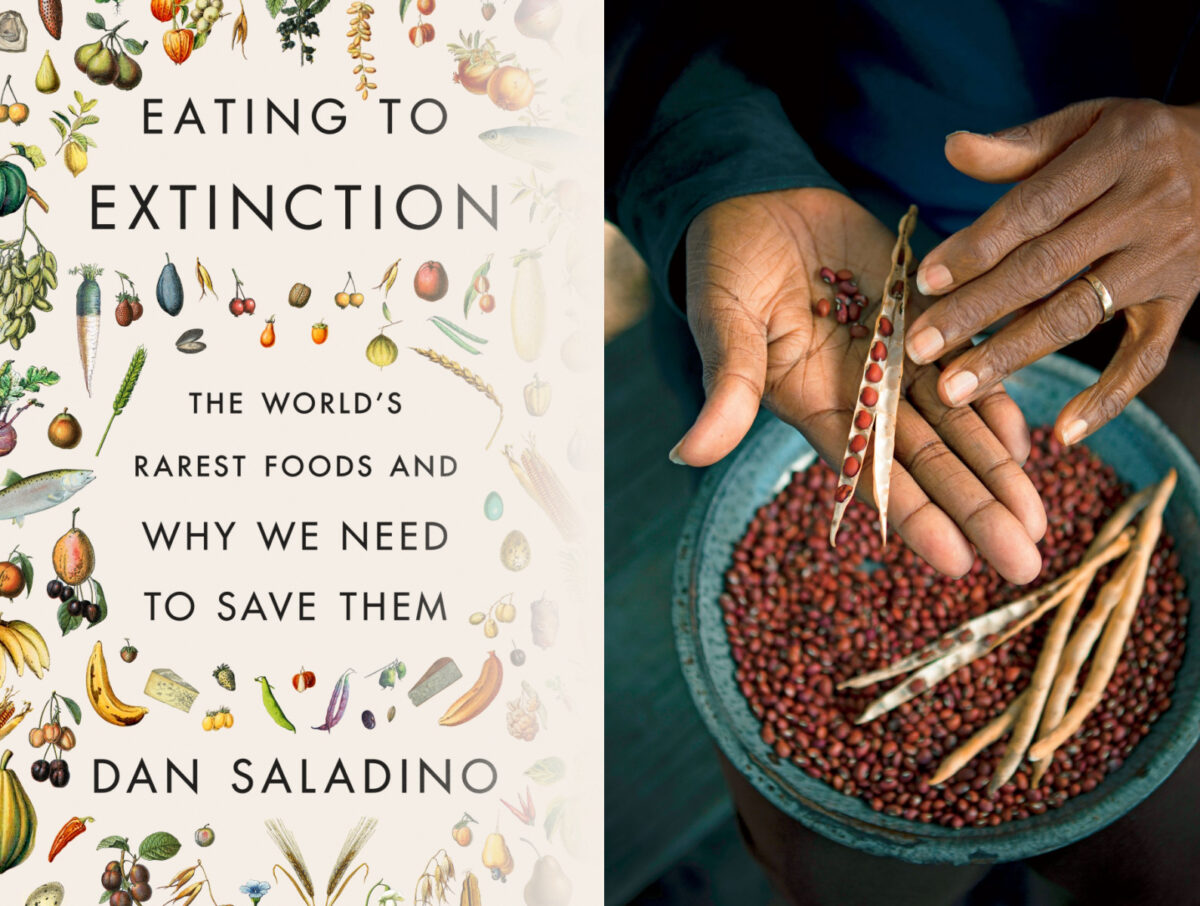

Excerpted from Eating to Extinction: The World’s Rarest Foods and Why We Need to Save Them by Dan Saladino. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2021 by Dan Saladino. All rights reserved.