Three Very Different Books Connected By a Quest for Identity

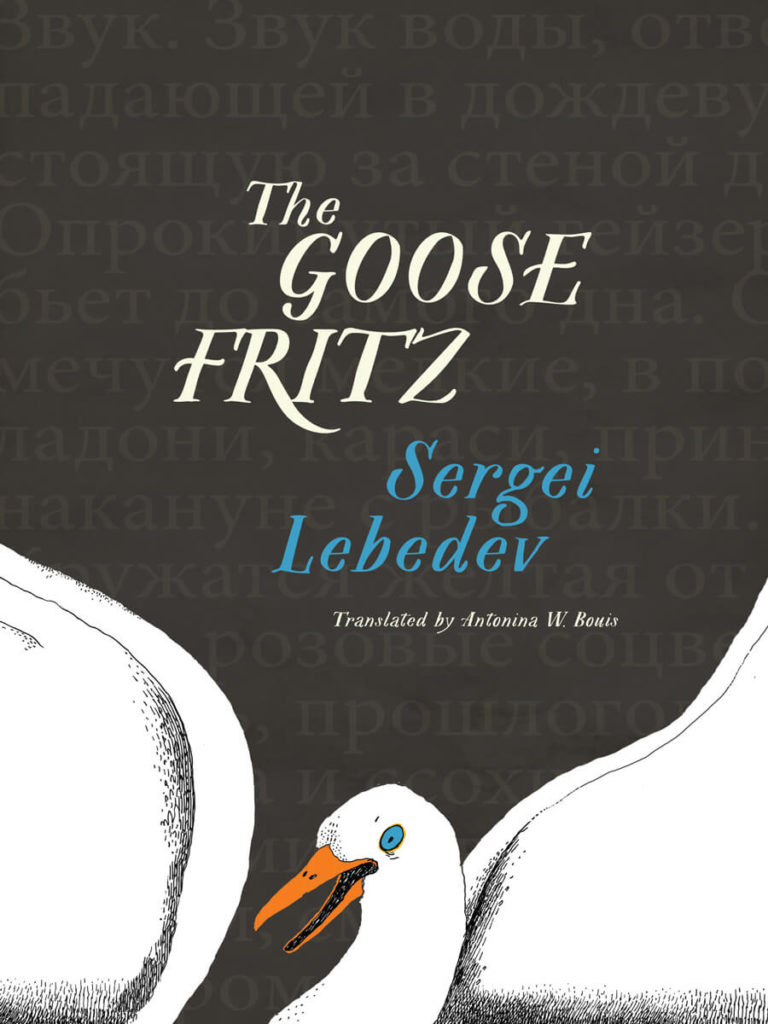

The Gooze Fritz, by Sergei Lebedev (New Vessel Press)

There’s a natural inclination to fill in the missing pieces of our personal narratives. It partially stems from the belief that understanding where you come from, can ultimately shape where you’re going. Such stories allow us to elevate our unknown ancestors to mythical proportions — a missing father can become a war hero, or a grandfather a healing wizard — offering the descendent a chance to create order from chaos and reframe their roots.

There’s a natural inclination to fill in the missing pieces of our personal narratives. It partially stems from the belief that understanding where you come from, can ultimately shape where you’re going. Such stories allow us to elevate our unknown ancestors to mythical proportions — a missing father can become a war hero, or a grandfather a healing wizard — offering the descendent a chance to create order from chaos and reframe their roots.

Kirill, the main character in The Goose Fritz by Sergei Lebedev, doesn’t initially set out to elevate his ancestors, but he does attempt to control his destiny by creating a linear arc of the past. As a child, Kirill was the sole companion of his grandmother Lina, as she took secretive trips to the German cemetery in Moscow. Unquestioning, he accompanies her for years before understanding the family’s German origins. It’s a secret that seems so far removed from the American psyche — a nation of immigrants — yet so apt in a time of increased nationalism.

A historian by trade, Kirill turns down a research position at Harvard to instead unravel his family’s secrets. He returns to his grandparents’ home outside of Moscow to write a book, the literary journey of a cursed family plagued by death and misfortune since their arrival in Russia in the mid 19th century. He looks at his family origin as duplicitous, and mercurial: “Kirill had long known whom the book would be about. About faces and masks, fractured fluid personalities, the Januses of history.”

As he begins to untangle the crossed and missing branches of his family tree, Kirill is forced to confront his known communist history and the unknown wealthy steel industrialists his family had once been. His journey takes him back centuries and across the continent in attempts to understand the political and personal reasons that drives someone to set up life in a foreign country.

Lebedev deftly weaves a narrative of otherness that has never felt so timely. From the very beginning of the novel, the reader is reminded of what happens when you draw superficial divides between groups of people. Despite generations born on Russian soil, Kirill’s family is designated as the enemy, first for being German, then for being wealthy, before coming full circle as German enemies again. The designation of otherness is fleeting, showing just how quickly someone can fall from grace. With each proverbial changing of the guards, the cycle of violence is continued, driving someone else to extract their revenge. – Meghan Udell

Purchase The Goose Fritz here (20% off)

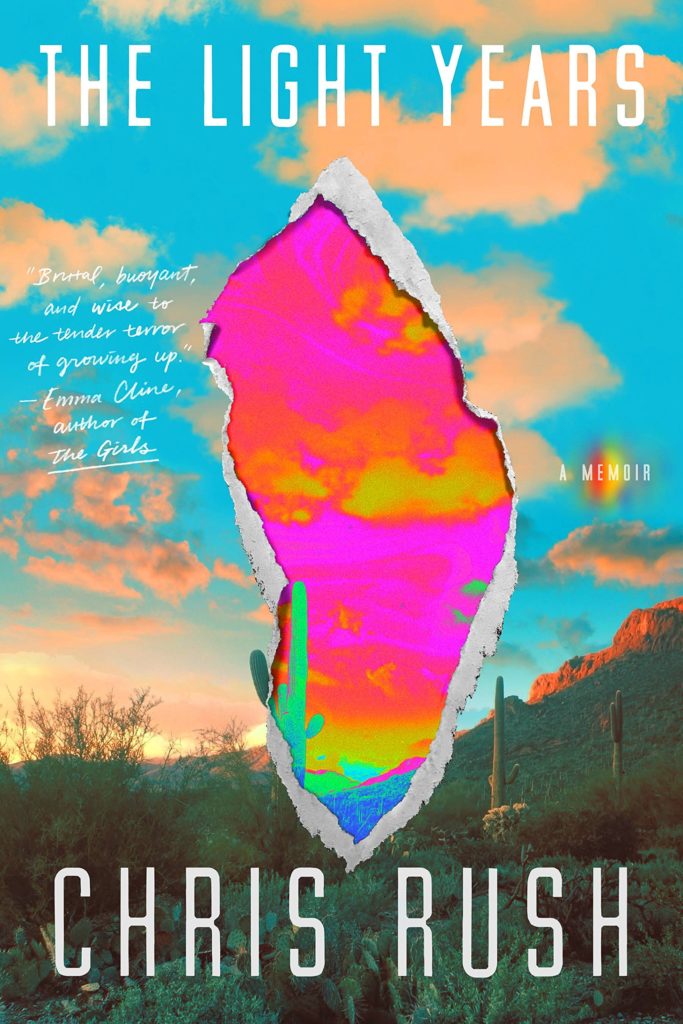

The Light Years, by Chris Rush (FSG)

It may be true that everyone has a book inside them, though if you’ve ever tried reading Paris Hilton’s Confessions of an Heiress you’ll know that not everyone has a story worth telling. Chris Rush, an artist and designer who lives in Tucson, not only has one hell of a story, he also has the talent to bring it to life. You can open his gorgeous memoir, The Light Years, to any page and the prose will leap out—funny, charming, effortlessly descriptive. You can see the writer he became in the 11-year old boy he is in the book’s early chapters—selling his home-made paper flowers to the ladies at his parent’s bridge party, erecting a life-size statue of the Virgin Mary in his bedroom, prancing around in a pink satin Pucci cape he found at Polly’s Bric-a-Brac. “For a week, I wandered the neighborhood in my cape, feeling potent and magical, a vampire-saint prowling the earth,” he writes. “In a Transylvanian accent, I asked people: Do you like my Pucci?” When his father forbids him to wear the cape any more, Rush is puzzled. “Later, during an argument with my mother, I heard him us a new phrase. “The boy is a goddamn queer, Norma—it’s obvious.”

It may be true that everyone has a book inside them, though if you’ve ever tried reading Paris Hilton’s Confessions of an Heiress you’ll know that not everyone has a story worth telling. Chris Rush, an artist and designer who lives in Tucson, not only has one hell of a story, he also has the talent to bring it to life. You can open his gorgeous memoir, The Light Years, to any page and the prose will leap out—funny, charming, effortlessly descriptive. You can see the writer he became in the 11-year old boy he is in the book’s early chapters—selling his home-made paper flowers to the ladies at his parent’s bridge party, erecting a life-size statue of the Virgin Mary in his bedroom, prancing around in a pink satin Pucci cape he found at Polly’s Bric-a-Brac. “For a week, I wandered the neighborhood in my cape, feeling potent and magical, a vampire-saint prowling the earth,” he writes. “In a Transylvanian accent, I asked people: Do you like my Pucci?” When his father forbids him to wear the cape any more, Rush is puzzled. “Later, during an argument with my mother, I heard him us a new phrase. “The boy is a goddamn queer, Norma—it’s obvious.”

The Light Years is about a gay boy who finds liberation in psychedelic drugs and the burgeoning hippy movement of the late 1960s, but it’s also about mothers and fathers, screwball friends, first loves, and leaps of faith that sometimes land painfully. Although much of the action proceeds in a haze of marijuana, it’s less a drug memoir than a meditation on journeys taken, real and metaphorical, to find a home in the world. Rush also writes without rancor about his philandering father and suicidal mother, giving the book a clarity and generosity that makes the experience of reading it feel beneficent and redemptive. And the characters that populate the page feel fresh and true in ways that creep under your skin, and stay there. – Aaron Hicklin

Purchase The Light Years here (20% off)

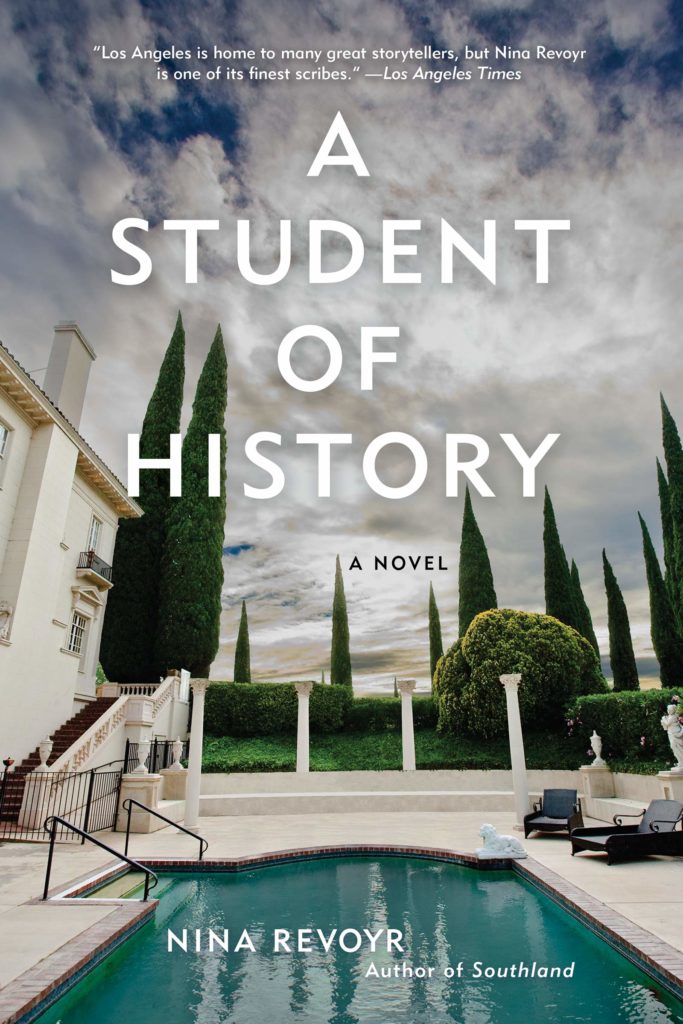

A Student of History, by Nina Revovr (Akashic Books)

On Tuesday March 12th, the Internet remained gleefully transfixed to the scandal of Operation Varsity Blues as it unfolded across social media. There was little expectation that the wealthy would suffer any real repercussions, but there was something deeply satisfying about watching Aunt Becky have to face even the faintest shimmer of accountability for her flagrant disregard of the rules. In a world where the rich often act with impunity, there’s always been a certain joy in watching them get their comeuppance. It’s a feeling Nina Revoyr relishes in A Student of History, even more so than the seemingly central theme of betrayal.

On Tuesday March 12th, the Internet remained gleefully transfixed to the scandal of Operation Varsity Blues as it unfolded across social media. There was little expectation that the wealthy would suffer any real repercussions, but there was something deeply satisfying about watching Aunt Becky have to face even the faintest shimmer of accountability for her flagrant disregard of the rules. In a world where the rich often act with impunity, there’s always been a certain joy in watching them get their comeuppance. It’s a feeling Nina Revoyr relishes in A Student of History, even more so than the seemingly central theme of betrayal.

Rick Nagano is a 30-year-old graduate student at USC, lost in the academic purgatory between the end of classes, and finishing his dissertation. In danger of losing his grant funding, he finds temporary salvation in the form of a wealthy employer— Mrs. W — the elderly granddaughter of a legendary oilman. Hired to transcribe her memoirs, Rick becomes Richard, acting as the aging beauty’s pseudo son. Seduced with a fancy moniker and even fancier clothes, he finds himself enmeshed as her platonic escort to charity events around the city.

Throughout the book, Mrs. W’s last name remains a mystery, both as a superficial deference to the privacy Richard wishes to grant her, but also as an amalgamation of the original land, and oil barons who enabled the rapid expansion of Los Angeles. Initially disquieted by his proximity to wealth and power, Richard becomes increasingly swept up in high society when he meets Fiona Morgan, one of the few people in Mrs. W’s circle who seems genuinely interested in Rick, in turn driving his fascination with her. The more he’s drawn to Fiona, the more he loses his sense of integrity, seizing the opportunity to betray Mrs. W by ignoring her fiercely private nature.

As we watch Rick get pulled further into the realms of Fiona and Mrs. W, we’re treated to a seamless transition between Richard and Rick — the intellectually capable, well-dressed historian, and the blue-collared son of a Japanese immigrant and Polish mother. This duality places him in a sort of no-man’s land between feeling superior to the moneyed elite, while conveniently sweeping the privilege of higher education under an impeccably worn Persian rug.

Revoyr insists that it’s not privilege itself which is bad, but rather its misuse, but her characters’ relationship to privilege are nothing if not complicated. The central characters of Mrs. W, Fiona, and Richard all behave abhorrently at times, with brief glitters of true humanity sitting just below the surface. Beautifully juxtaposed against a similar landscape of Los Angeles, A Student of History offers a voyeuristic look at the lessons one receives from life. – Meghan Udell

Purchase A Student of History here (20% off)