The journalist and biographer Jason McBride and I have some confusion about how we first met—definitely before we were in Germany together for a symposium. The marathon reading of Kathy Acker’s Blood and Guts in High School we both took part in? The Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery? KGB Bar in New York’s East Village?

There’s no such question in my mind with Lauren Elkin: twenty years ago, we were together in Professor Richard Kaye’s “The Decadent Imagination” course at The Graduate Center of the City University of New York. I now know her more through her books, chief among them 2016’s wide-ranging, adventurous and highly celebrated Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in New York, Paris, Tokyo, Venice, and London. Currently based in the UK, she promises further revelation in the forthcoming Art Monsters: On Beauty and Excess. I’m already baited.

Imminent publication of Jason’s first book, Eat Your Mind: The Radical Life and Work of Kathy Acker, long anticipated, prompted our virtual reunion. Out this November, the book has garnered much-deserved advance praise, including from Lauren (“An elegant, engaging account of one of the twentieth century’s most important writer-bandits, which traces the twists and turns of her life with great empathy and sensitivity.”) When she and I and Jason sat down before our respective screens, there he was with much art taped to a wall behind him I might have asked about; Lauren in Wisconsin for the first time, over her left shoulder a cardboard box reading “Tea Sets” resting on an outside table, a migraine having just left her (“I don’t think I’m meant to be in this atmosphere,” she laughs). It was hard to contain myself.

I wanted to be sure to nod to mentors. I wanted to appreciate the portrait of a rekindled familial relationship in Jason’s book, the “at once admirable and adolescent” quality of Acker’s work, and all it provides I had not yet been able to gather. We strayed beyond Acker now and then: Was it even possible to be a sellout today? I’ve redacted the part where we each copped to one classic book we’d not yet read. As the last evenings of these summer days were fading, we were going to talk about our mutual appreciation and abiding investments in the meaning and legacy of Kathy Acker’s work – while also gesturing to the future.

– Douglas A. Martin

MCBRIDE: My son is currently at an amusement park with my best friend, Derek McCormack, although it’s not going well. They started this tradition last year. The biggest amusement park, Canada’s Wonderland, is just north of the city. I’m afraid that they’re going to come back any second and just barge in on us, but fingers crossed, it will be okay.

MARTIN: I just texted one of the two children in my life to see if she had any Nancy Drew books, triggered by this near-mimic you do, Jason, at one point in your biography, like those ending “if you are sad that this one is over, just wait until Nancy’s next case!” Quoting you: “The book’s [Kathy Acker’s Rip-off Red, Girl Detective] final lines—”I’m no longer a detective. I’ll decide to be someone else.”—would also herald the next, significant chapter in her evolution as a writer.”

So maybe starting more with Lauren and evolutions, did you talk to any of the people that you worked with at our grad school about Kathy Acker?

ELKIN: I just read [her] on my own, or I tried to. In grad school, I was really focused on doing British modernism. I just wasn’t interested in American literature. I was reacting against America and anything that came from America, and I wasn’t yet a creative writer or didn’t think of myself as a creative writer. I wasn’t interested in reading to see what other people had done. I was like, I am a Virginia Woolf scholar, I work on her, and then obviously life took me in other directions.

MARTIN: When I saw the late scholar Jane Marcus’ name in connection to you, Lauren, looking back at Flâneuse, the flutters that I had… But I was thinking to ask you: At what point would your children be able to read Kathy Acker?

ELKIN: Uh, grad school, I don’t know. I guess at some point, he’ll be allowed to whenever he wants.

MCBRIDE: You know, my son doesn’t even like books. I don’t know if he’ll ever read Kathy Acker, to be honest. But he has talked about me having a crush on Kathy Acker, because I was so obviously fixated on her for his whole lifetime. I started working on the book soon after he was born. The very first interview I did in 2013 was with Kevin Killian. Kevin was in Toronto and he was giving a paper. I took my son with me to go see it because he was so young, so he was immersed at the very beginning.

[I] remained mesmerized by her to the point where I would only read things that Kathy recommended or I’d read the writers she referenced in exclusion of all other things. That obsession probably lasted almost a decade…she gave me an enormous syllabus.

Jason McBride

LAUREN: How did you decide to write a biography about her?

MCBRIDE: Kathy was the first, uh, Professional writer I saw read in public. I went to the University of Toronto and it was in my second year. It was a big literary festival that happens every fall. I had been a big Burroughs fan in high school. I had heard of her, probably through Derek. We went to go see her together and she just blew my mind. She was amazing looking. The stuff that she read was shocking and titillating and I was mesmerized. And remained mesmerized by her to the point where I would only read things that Kathy recommended or I’d read the writers that she referenced in exclusion of all other things. That obsession probably lasted almost a decade. Then after she died in 1997, kind of pre-internet, there wasn’t a lot of information about her. I’d read every interview I could find. I wanted to know so much more about her. I became a journalist and began to meet people who knew her. I knew lots of little bits about her life, but not that much, and just waited for somebody to write a bio. She seemed like such a perfect subject. Then nobody did. I would hear rumors about books that were in the works. Chris Kraus’s book was a rumor for a while. Then I finally just was like, fuck it. If no one’s going to write this book, and I really want to read this book, I guess I will have to write it. So I contacted Matias Viegener, her executor, we had an hour-long phone call and he was, to my surprise, extremely supportive of the idea. I think he similarly was so desperate for a biography to exist. And having written many magazine profiles over the years, I kind of thought I could do this in a couple of years at most. And now 10 years later here it is.

MARTIN: It is the book that I wish had existed before I sat down to write my book, 100%.

JASON: That’s kind of you to say, Douglas. When your Acker book came out, I was like, okay, I don’t need to write my book. These books did start to come out. Like Chris Kraus’s book did finally come out and introduced a lot of people to Kathy and your book did the same. There was suddenly this groundswell of interest in Kathy that hadn’t existed when I first started on the book. I was so pleased to see that. Your book came out in 2017. Is that right?

MARTIN: Yes.

MCBRIDE: I still had so much work left to do at that point. Then I thought to myself, you know, how many biographies of Sylvia Plath are there? How many biographies of Virginia Woolf are there? I think that Kathy deserves as many, if not more. She’s an infinitely rich and complex and fascinating subject.

MARTIN: Lauren, were you ever in a room with her?

ELKIN: She died in ‘97. I was in my sophomore year of university and I was still a theater person at that point doing jazz hands. I was studying musical theater at Syracuse, and then I transferred to Barnard the second semester of my sophomore year. That’s when I became, you know, a serious intellectual. I’d never heard of any of these people before that time. I never heard of Simon de Beauvoir until Barnard. I’d heard of Virginia Woolf because of the Indigo Girls song. That was it. But no… When I was researching I guess my MA or my Ph.D., I just remember coming across Kathy Acker’s name, so often in connection with people like Jeanette Winterson or Djuna Barnes, this lineage of radical experimental— often queer—writing by women. My interest basically went up to 1945 with some allowances for Jeanette Winterson, who I was obsessed with for a really long time. So I sort of glanced at [Acker’s] Empire of the Senseless, because that was the first book of hers I came across in whatever bookshop I was in. And was like, okay, I should know who this is. I should get to grips with whatever this version of experimental feminist writing looks like. Jeanette Winterson by comparison is super lyrical and very readable and engaging and quite beautiful and philosophical. And here was this punk woman just tearing everything up and doing obscene things to stuffed animals. It really brought me up against the limits of myself and who I could conceive myself to be. That was a big motivation in writing [my current book] Art Monsters. My life right now is outwardly very heterosexual, but I would never pin myself down into any particular box, sexually speaking. Acker’s work kind of conjugated a version of me that I didn’t recognize and it made me nervous, I think. And I didn’t like feeling that way.

MARTIN: I would have never actually read Marguerite Duras if Kathy Acker hadn’t said somewhere she was her favorite writer. Jason, is there anything you feel like she brought you into?

MCBRIDE: Yeah, I feel like she brought me into everything. I never went to grad school. I barely finished my undergrad. I don’t think of myself as literary critic or an academic. I’ve taught very rarely. She was an education for me in many ways. As an undergrad, I did study theory, philosophy, a bit, but I feel poorly educated, I guess. She gave me an enormous syllabus. It was brought home to me so often in writing the book that she herself was so well-read and so educated. And knew so much, and was able to take that learning and transmute it into something seemingly so abrasive and blunt and confrontational. And to do that was such an odd and magical thing for a writer to do, to have that there, but then to shed it, it really seemed perverse and alluring at the same time. I’m still so fascinated by her. I was exhausted by the time I finished the project, but I was so pleased how she kept revealing new things to me throughout the whole 10 years—shocking.

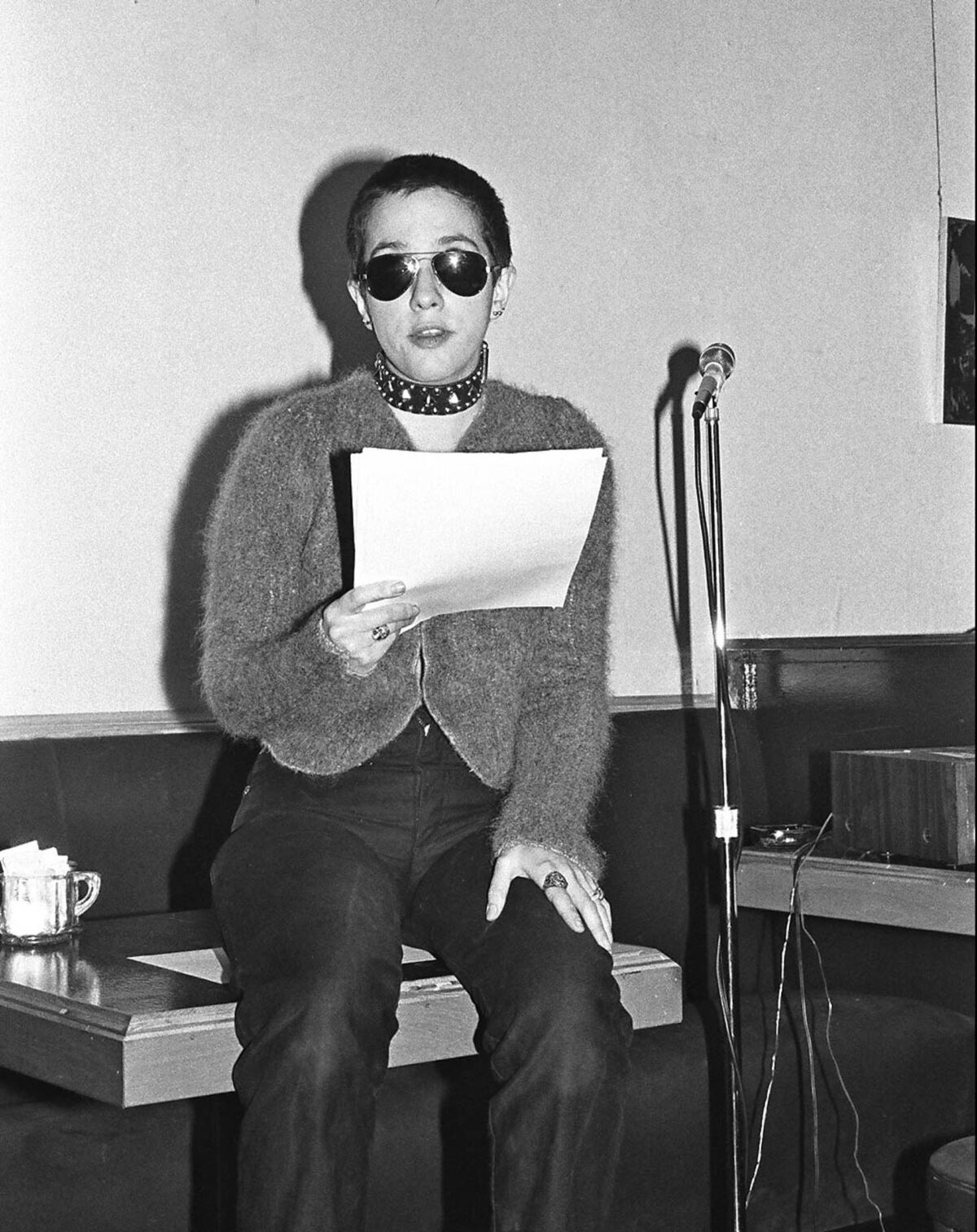

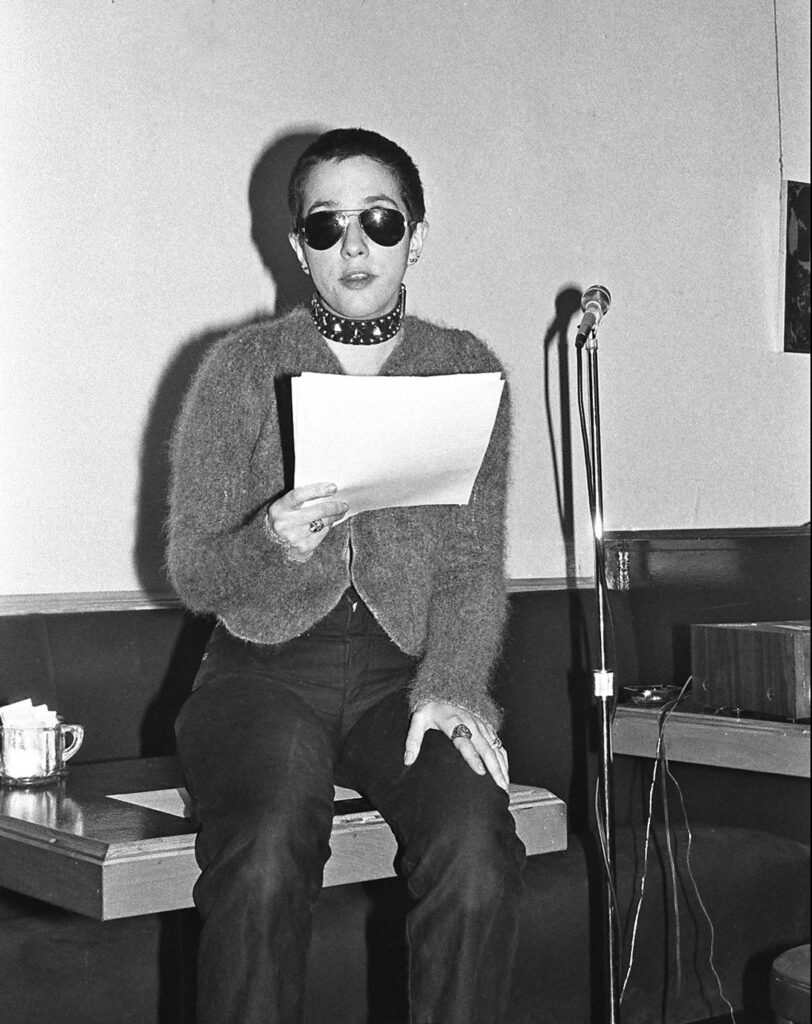

Acker reading at Mickey Ruskin’s Chinese Chance in Greenwich Village, circa 1979. (Photograph by Marcia Resnick)

MARTIN: One of the people I worked on Acker with in grad school was Eve Sedgwick, who turned on a light bulb for me when she was wondering how much of an autodidact Kathy was. I said, “What’s an autodidact?” The feel of that was one of the reasons I gravitated to the work as well, like her anger with academia and wanting those spaces to hold her, but also feeling like some ‘other’ within those spaces, never completely who she wanted to be. It’s like me, what’s wrong with me, still not tenured after fourteen years at the same school! But it’s so wonderful, that by the end of her life she has formulated a kind of school around herself.

MCBRIDE: It’s fascinating, that part of her life when she goes to San Francisco and she does find real joy and security and nourishment… teaching in a very particular kind of school. She would complain about teaching, but she obviously got so much out of it, her students and the community that they represented. She had very particular kinds of students. But she really fostered a climate of unique education.

MARTIN: I wrote my dissertation in six months because I just wanted to get out of grad school as quickly as possible. I’d already written a novel. I had this thing in me that was like, if I don’t get this done, I’ll never write a novel again. And to me that seemed like everything. I didn’t have much time in her archives, just two days, one weekend. I love the syllabus there in North Carolina where she’s planning to tell her students about Hélène Cixous’s “school of the dead.” That was for me a real turning point: the teaching can be your art. I felt that way with Lauren’s No. 91/92 that I used recently in a nonfiction writing class. One of the real pulses, a heartbeat through that book, is showing that capacity. I was so struck by its turn to Woolf. We can bring the work that we want to be doing into that space. And Lauren, to go towards some of the ideas that you rehearse in the introduction to the Art Monsters, can we be in the lines between boundaries? I think the books I like come out of those ‘monstrous’ spaces.

MCBRIDE: Completely.

ELKIN: I miss teaching so much, but it feels politically impossible in Britain. I don’t know what it’s like in the U.S., but the Tories have broken the British university system. It hangs precipitously in this balance between the American model and the European socialist model. And it doesn’t work. The people, the lecturers are given way too much admin and it sucks up all their time, and there’s no time left to do your research or your writing.

MCBRIDE: This is something I’m sure you both also struggle with: trying to find the balance between making a living and working on something that’s not paying you any money. I still don’t how to do it really. That’s something Kathy struggled with throughout her whole life. When she had inherited a significant amount of money, she lived a bit more extravagantly than any of us, probably, but it was a constant problem. And yet she was able to do the work that she wanted to do, I think, most of the time. But she never stopped complaining about it.

MARTIN: This is one of the points of her life that I think you are just gangbusters, the way that finances actually did work through her life, so lucidly, so depressingly. How much she did really work within that struggling space financially that later became more the persona. I do think that the money from her grandmother was what eventually afforded her a kind of time and space to figure out how to put together some books that would then command actual advances. And you are so masterful at showing how all the pieces line up. Here’s being in the perfect place at the perfect time. And here’s where a drift starts to happen… I also appreciate your structure: starting not with her death, but a couple years before in ‘95. You know, with her on her motorcycle being in the bliss zone and then circling back to ’95 over the book, the exhaust trailing after that, writing that. Such an inventive solution to the problem of cradle-to-grave biography, or what to do if we start with the death and can only then come back there.

ELKIN: At a certain point in the revision process over the last few months of Art Monsters, I realized that I was writing about all of these dead women—Kathy Acker, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Ana Mendieta, Hannah Wilke, Carolee Schneemann—and that in each of the chapters on them, I had a little moment about her death. In the Cha section, I’d specifically been trying to write against her as the girl who died, but that it’s a kind of important part of her story, I mean Ana Mendieta as well, but…I have a whole chapter about breast cancer and Kathy and Hannah Wilke’s photographs of herself when she was suffering from cancer at the end of her life, and Jo Spence’s mastectomy photographs as well. It was just a real problem in the book, figuring out how to deal with the narrative of people’s lives that were concluded, and to what extent the ending affects how we read. Like, how do we deal with the work as the work and not have it be clouded by the death?

MCBRIDE: I can’t wait to read Art Monsters. May I talk just for a second about Carolee? One of the great gifts of writing this book was the opportunity to meet so many people that I had admired and revered in my early life. Carolee was one of them, and to go to her house and spend an afternoon with her and then go to dinner with her and to have her kiss me on the lips at the end of the evening was just like, oh my God, it was magical!

ELKIN: Oh my God, you kissed Carolee Schneemann on the lips.

MCBRIDE: She kissed me. She was just so generous and unbelievably sweet and we hung out with her cats, of course. She spent a long time trying to find photos for me. I was just like, God, I can’t believe that she’s giving me this time.

MARTIN: The time that you give her in the biography, too, was so enriching to me, and the credence that you give to her own approach to cancer struggle.

MCBRIDE: When she told me that she had talked to Kathy about how she had treated her breast cancer, it finally revealed to me why Kathy had made that decision. I felt like it was a key to Kathy’s choice. Everyone always thought, oh, Kathy was so headstrong. She was this, she was that. But she had seen somebody who had successfully treated her cancer with an alternative treatment. Why wouldn’t she try it?

MARTIN: I have something underlined in your book, Jason, the most astonishing sentence of all to me: The smell inside her masks had become overpowering. That is just beyond.

Here’s the other quote that I want to ask you both about:

Almost alone in her tenacity and nerve, she had completely reoriented our understanding of literature and what literature could do. For all of her books’ vivid vulgarity, they asked fundamental questions. How do I cope with the pain of being unloved? What is good art? What is art good for? What knowledge exists outside our conscious minds? Where is home, and how do I get there?

MCBRIDE: Can I ask you each a question? You’re reading her work a bit, still, I guess Lauren, because you’re working on Art Monsters. Douglas, I don’t know how often you look at Kathy’s work these days. But how much do you get out of it now versus how much you got out of it when you were younger when you were first reading it?

ELKIN: Well, considering I got nothing out of it when I was first—

MCBRIDE: Right, you were like [gestures] throw it across the room…

ELKIN: I still don’t feel like I get it…get it right. But it opens up so much for me now. “What is good art and what is good art for?” may be the most important question for me in this book. But it may be, in my life as a critic and a writer, why do we do what we do? Why is this important? Why not be a surgeon? And Kathy Acker does not give us answers to that, but she gives us so much to think about or think with, in terms of why we go to art. Here are these characters kind of like astronauts in a free-moving space, completely undefined. Now it’s Paris, now it’s New York, now it’s Algeria, and you can’t get ahold of anything. That seems like the most politically important thing that you can do as a writer: refuse any kind of narrative surety. It’s all simultaneous. I’m still obviously trying to come to grips with her as a writer, but that’s probably the major thing for me right now. That keeps me engaging with her and makes me think she’s someone you can’t just throw across the room and be like, what is this smut?

MARTIN: I’m always piecing it together with other things, I’m always dipping into it, so in a way it’s like the work will never end. I do think of it still as a bit like music. The more one’s ear becomes trained, the more one’s able to hear. And I feel like as I continue to read new things, not only about her, but also by her, I go back with keener senses. To use a cuter metaphor, it is like a toy box to me.

ELKIN: A very apt metaphor for someone who loved stuffed animals.

MARTIN: I loved that Jason wrote so much on those animals. I don’t think it was when I was writing my book, maybe later, but doing something Matias had asked me about, I was like, postscript, “Can I have one of the stuffed animals?” But he never responded. I still need one.

MCBRIDE: He gives away her stuff all the time. Yeah, it’s funny. People have talked about this a fair bit, what kind of writer Kathy would’ve become had she lived, but I think her writing on aging would’ve been so fascinating. I mean she died at the age of 50. Her writing for the most part is writing about young people, and it appeals so often to younger people, but I still find stuff in her work that is so much more resonant now that I’m older. She would’ve written the great internet novel. She might very well have become someone like Genesis P-Orridge, just modifying her body in so many different ways. You can stay up all night thinking about this.