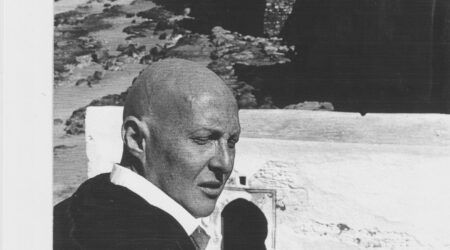

Richard Haines was five when he began drawing. Gardens, mostly, and wedding dresses. “The gay gene activated,” he says. “All the other kids were drawing World War II bombers on their notebooks. On mine were roses and gowns.”

All gay boys have some version of this story, but the droll portrait of the young kid slowly figuring things out for himself is steeped in melancholy, too. Because Haines knows how the story ends, at least for his post-war generation, sprung from the cage of dull 1950s conformity by the liberating hand of Stonewall merely to be flung into the maw of catastrophe. In New York, where he shed his navy blazer for a t-shirt and 501 jeans, the bacchanal was everywhere, until suddenly it wasn’t. “You could not go out and buy a quart of milk without getting laid,” recalls Haines. He remembers reading the notorious “gay cancer” story in The New York Times, and not quite taking in the significance. “I was at a party that summer with my best friend, who was very smart. And he said, ‘A year from now, a lot of us are going to be dead.’ We all laughed, like, ‘Peter, you’re being really dramatic.’ And he was right. And he was one of them.”

Haines was in his early thirties when his friends began to die. So, he did what he felt he needed to do in order to survive. He married a woman. Back within the fold of conformity, life was easier, safer. “I never tried to present myself as straight, but being white and being married to a woman was a really different experience,” he recalls. “Suddenly the doors would always open.” He adopted a child. He married a second time. The years passed. “I can’t even fathom what my life would be like if AIDS hadn’t happened,” he says.

Once you know all this, you see more clearly how Haine’s tender portraits of young men resonate with the older man’s ache for what has been lost. “It’s almost like Hiroshima, when you see the silhouettes of people kind of burned into the stone,” he says. “A lot of it, I realize, is me trying to capture something or relive it, which is my youth that vanished really fast.” In his twenties he had friends; by his thirties they were mostly gone. “In a way, it’s fresher now than it was 20 years ago,” he says. He is talking of wounds, of the disappeared. “I think about them constantly.” He is in his early 70s now, but still working in the shadow of what happened 40 years ago. “I’m still processing the kind of trauma of being so ill equipped, of being 30 and in mourning constantly, losing my circle of friends who I really loved. And I know that they loved me. I’ve always been trying to recreate that, and I never really have been able to.”

I’m still processing the kind of trauma of being so ill equipped, of being 30 and in mourning constantly, losing my circle of friends who I really loved. And I know that they loved me.

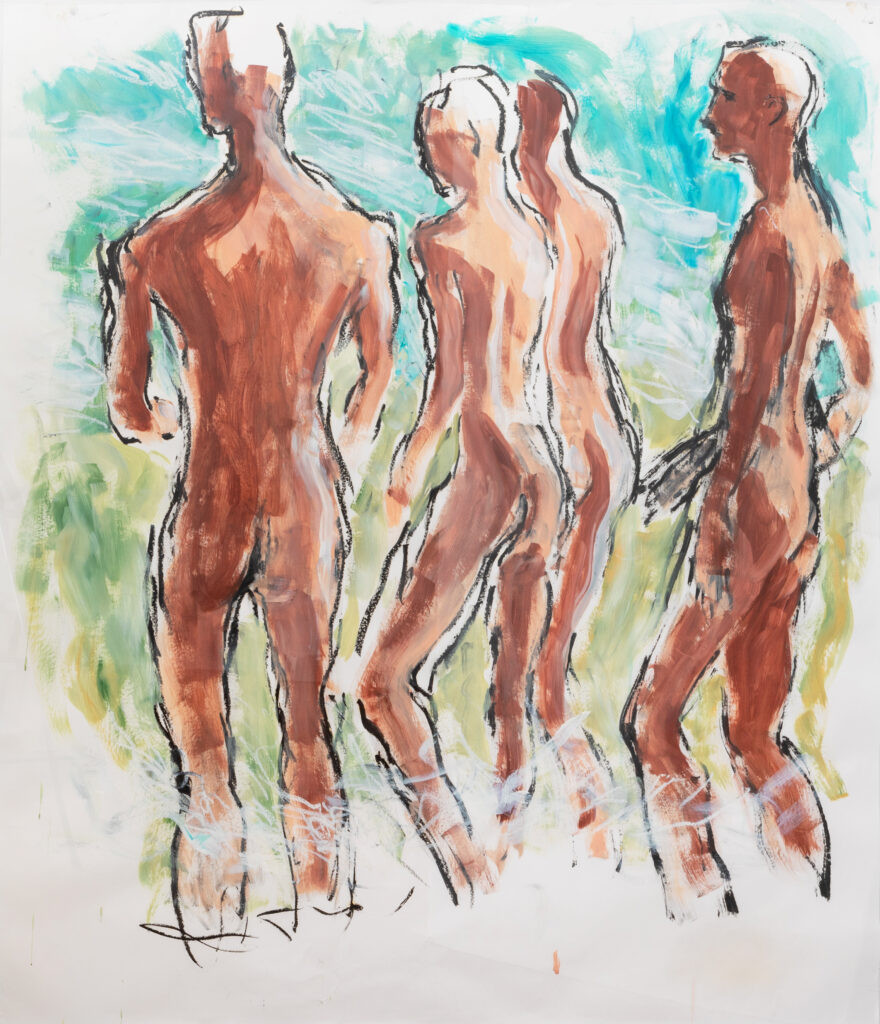

We are in Haines’s studio in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, on a soft April day, surrounded by oils of lithe young men, often nude, sometimes not. Ripe with color, pleasing to look at, the men exude an easy confidence reminiscent of Toulouse Lautrec’s studies of women, alone or in bed with each other, unperturbed by the artist who sat sketching them. We admire Haines’ subjects in part because they admire themselves. “I can’t remember what it was like being 30, but I was not comfortable with my body,” says Haines. “These guys are really comfortable. And I think they love to be seen. Who wouldn’t love to be beautiful and be seen?” In an introduction to the catalog for Haine’s new show, Paradise Lost, at Daniel Cooney Fine Art (thru June 30), the writer Wayne Koestenbaum describes them as “honest nudes,” by which perhaps he means that nothing is hidden. The men own their beauty; the artist owns his admiration. Some could be tableaux from lives that continue, as it were, off-canvas. In “Rowdy Ruff Boyzz” (2023) two men spoon gracefully on top of the rumpled bed sheets, the rowdiness presumably behind them–and ahead, too. In “Quatre Hommes Dans L’Eau” four bronzed men feel timeless as the summer day on which they have been memorialized. They could be strolling the Fire Island Pines in the 1970s. Or you may find them there tonight at the Sip n Twirl. Haines’s art is a time portal–then, now, and then again. His youth in the 1970s and 80s reflected back in the men he paints today. We, too, like Haines, examine these men as if from a distance, curious onlookers. “They’re all queer men,” he says. “But I always feel kind of outside, especially with couples. They reflect something that I can’t quite get, which is their intimacy and their love.” He pauses. “I mean, it’s a long story, a lot of therapy.”

Edo Dives, 2019. Oil and acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of Daniel Cooney Fine Art

The art, of course, is part of that therapy, but then it has always been. He was five-years-old when his dad, a naval commander blessed with movie star looks, returned from a six-month tour of duty. “He came back with an STD, and went to hospital, and they either gave him the wrong medication, or he had an allergic reaction, and he almost died,” recalls Haines. “He left this kind of hero, and he came back just this broken, withdrawn person for the rest of my life.” It would be another 50 years before Haines got the full story from his mother, but his parent’s marriage languished in a slick of recrimination and resentment. There was a lot of drinking. “The wheels just came off. And no one talked about it. That’s when I started drawing because I couldn’t cope with it. There were pictures of me with him before, at the pool, or just leaning into him. He was this big, romantic figure in these navy uniforms. He was everything. And then, he just vanished.”

Was there a nadir in all this? Possibly his mother’s drunken confessionals while his father slept upstairs–“so Tennessee Williams,” says Haines. “I would just sit there traumatized.” Or possibly his time at Robert E. Lee High School in suburban D.C. “Nine hundred kids that all wore navy monogram sweaters and chinos.” Haines rolls his eyes, but of course he was one of them. “I had everything monogrammed, my sweaters, my wallet, my belt buckle,” he recalls. “I just wanted to fit in.” And did he? “I thought I did, but I didn’t. I became the class artist. And that was, again, my way of surviving.” Somewhere along the way he discovered Georgetown, museums, French Vogue. Freedom. “The minute I found out there was something else, I just started getting the fuck out of the suburbs.”

I was supposed to stay for a week. And I realized I could have sex with men, so I just kept prolonging coming back… it was the first time I could really be free. No-one was looking. No-one knew.

He got all the way to Paris, inspired by a lesbian couple that ate at a restaurant he was working in shortly after finishing college where he studied graphic design. “They’re like, ‘You have to come to Paris. And I was like, ‘Of course I do’. So, I saved up all my money as a waiter, and went to Paris, I think in May ’74. I was supposed to stay for a week. And I realized I could have sex with men, so I just kept prolonging coming back.” For the best part of a month he danced at Club Sept and cruised the Tuileries in his flared jeans and Gucci loafers. Days spent at Cafe Flore, fortified by cigarettes and Coca Cola, reading Interview magazine, were followed by nights in two-star hotels banging a Greek art dealer. “I didn’t realize until much later that it was the first time I could really be free,” he says. “No one was looking. No one knew.”

After Paris there was no going back, only forward. Haines moved to New York. His friends moved there, too. There was nowhere else. He joined the city’s first gay gym and grew a mustache. He got a job working for Perry Ellis when there was no other American designer worth working for. He got a boyfriend. Life was great, better than. The rest of the story we know. Goodbyes and funerals. Haines still chokes up talking about it.

Unexpectedly, Haines and I find our way into a different conversation. About money. About losing it. About being men of a certain age who wake up one morning feeling used up, discarded. For Haines that happened in the early 2000s, after he lost his job as the creative director at Nautica. “It was my final Garmento job, because I was so ill equipped for those politics. I got devoured constantly,” he says. Newly-divorced, with a ten-year old kid, Haines ran into financial quicksand. He was selling art books for groceries. A trip to the Jersey Shore to leave his child with a relative became a bellwether of how quickly a life can unravel. “They were like, ‘Oh, Dad, I forgot my flip flops, can we go get a pair?’ And I just thought… If I get them I don’t know if I have money to get us back to New York.” Haines seethed with humiliation, anger, anxiety.

What saved him was drawing. It was, is always, the buoy he needs. “I started drawing again because no one would hire me as a designer.” He was 55, just putting one foot in front of the other each day. But he was also drawing. “I was just so fucking happy to draw,” he says. “I would draw anywhere. I would go to a show at the tents at Bryant Park and if they wouldn’t let me in, I’d stand outside and draw.” Friends told him to start a blog (remember those?) to share his work. He offered to draw portraits for $50 a pop, and The Cut picked it up and wrote about him. J. Crew hired him to do some drawings for $5000. He moved out of his bedbug infested sublet of a sublet, and into an apartment in Bushwick, Brooklyn. “I had no money, and no credit, nothing,” he says. But his work was getting noticed. Money trickled in. Bruce Pask at The New York Times offered to send him to the shows in Europe to draw the best of Paris and Milan, a game changer. Prada invited him to visit the showroom to draw, and then hired him for a project.

I remember seeing Haines around that time in Milan (once, to my enduring pleasure, he drew me sitting across from him at a show). I loved his splashes of color, the way his quick elegant lines created the impression of movement, a certain ephemeral quality, the sense of air moving. His new work is a leap forward, though. The paintings reflect all the suppleness of his drawings, but there is a Fauvist quality, a fierceness. In “Mordechai with Screen and Mirror,” (2023) the canvas pulses with color, while Mordechai sits pale and pink, wearing only a pair of black socks. It’s infinitely touching, full of pathos and empathy. There are a few other Mordechais. There’s “Blue Mordechai” (2023), and Mordechai in front of striped fabric and a mirror (this time with white socks). In each Mordechai there is an ease, a familiarity. “I want to have them be comfortable and put them at ease, and I also want to hear their story,” says Haines. Kostenbaum (in the catalog essay again) writes that Haines’s figures “manage to wear the look of a young flower being observed by an older flower.” The older flower, in this case, is a survivor of a plague. You might not be wrong to think the young flower represents all of those who did not survive with him. It’s no coincidence that Mordechai is 30, or thereabouts—about the same age as Haines when AIDS turned his world upside down.

Haines says the journey from illustrator to painter was not always easy. Often he slips off to MoMA, a 30-minute subway ride away, to see how others have figured things out before him. If he’s struggling with a particular shade of green, he’ll find eight varieties of it in a Picasso. Still he has to fight the sense of being an intruder. “It’s entering a world that’s not very welcoming to illustrators and people in the fashion business, and it’s coming up against this history of Western civilization and art,” he says. “Who am I to take this on?” He remembers reading a book by the author and children’s illustrator Ludwig Bemelmans and feeling validated when Bemelmans recalled his one transition from drawing to art. “It’s really humbling because I can do a drawing, and I know it’ll be a really good drawing but to make that segue to canvas and to oil was really challenging. I’ve had to really recalibrate my brain.”

But Haines has found his rhythm now, and the work is coming thick and fast. Next he thinks he may do a series of men in bed, another nod to Lautrec. “I can’t look for anyone’s approval,” he says. “I can’t look for acceptance. I just have to keep doing this.”

Richard Haines: Paradise Lost is on view at Daniel Cooney Fine Art, Manhattan, through June 20.

Rowdy Ruff Boyzz, 2023

Quatre Hommes Dans L’eau, 2020.

Three Skaters, Manhattan Avenue, 2023

Mordechai with Screen and Mirror, 2023

Austin with Blue Socks, 2022

Hi, It’s Me, 2023