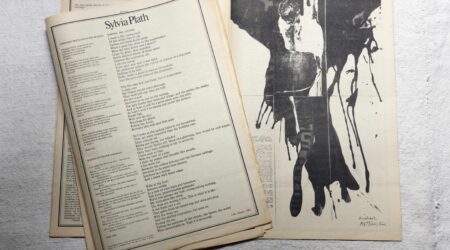

People fell in love with Ted Hughes with astonishing ease. In Ted Hughes: The Unauthorized Life, Jonathan Bate wrote of one woman who was so completely unmoored by meeting the poet that she hastened to a bathroom to vomit. But it is Hughes seven-year marriage to Sylvia Plath that has engendered fanatical interest. In this extract from her memoir, The Burnt Diaries, the author and magazine editor Emma Tennant recalls her fascination with Plath, intensified by her own tortured affair with Hughes, and the day she tried to make him talk about his former wife.

“There has been so much to do with the magazine, and with the new book I’m writing, that the now-customary silence from Ted has only fueled my imagination, as if the messages he sends go straight into my work. Nevertheless, I’m still convinced he’ll tell me everything one day, and I’ve been piecing together all I can on the one subject Ted Hughes will never talk about: Sylvia Plath.

I know there’s an embargo on her being mentioned—though, bizarrely, Ted’s sister Olwyn talks about her in tones of frank exasperation, as if Sylvia were still alive and causing maximum sister-in-law trouble. I suppose this is true, as death has made her immortal—but it must be due to the fact that I’d just been reading the collection of her prose, Johnny Panic, the ‘Bible of Dreams’ just issued by the Plath Estate, that I found myself blundering into the forbidden chamber as soon as I saw him again.

We’re driving out to Chiswick, it’s a fine day and there is talk of those poets Ted most admires—Seamus Heaney, Joseph Brodsky and Eastern Europeans such as Zbigniew Herbert and Pilinszky, whose bright, jewel-sharp lines have been brilliantly translated by Hughes, introducing a readership the poets could never have dreamed of before they were picked for prominence by a major figure on the poetry scene. I keep thinking this is Ted’s ‘good’ fame as opposed to the ‘evil’ one which is also forecast for him: Thousands of aspiring writers have reason to be grateful to him, and students who need a window onto a wider world that the very English cadences a Philip Larkin or a John Betjeman can supply.

‘What are you thinking?’ Ted asks me as the little car whips onto the Westway (he has just announced it would be more fun to go towards Oxford than to Chiswick House or Kew).

I reply that, for someone so imbued with foreign poetry and prose, I wonder he doesn’t feel like leaving England, just now going through its most parochial, whingeing and self-hating phase since the loss of Empire. ‘Wouldn’t you be happier’—my mind roams the wild spaces I know he likes —‘in Chile or Argentina, or somewhere?’

Ted snorts, shakes his head. He has told me in the past that he has Spanish blood, explaining his and his sister’s unusually striking appearance—but now, stealing a glance at him sideways, I see a Yorkshireman, stubborn, cleft-chinned, with wily eyes and a jaw like iron. ‘If I left England,’ Ted says, and chooses the most melodious of his many tones of voice to deliver the punchline, ‘I have a feeling England would collapse. We’re a little tribe here, you know, with the Queen looking after us. Where would I go?’

I find it hard to believe that a man so reviled—for almost every review of his narrative poem Gaudete was bitingly cruel, as transparent in its dislike of the poet and his magical, sometimes Satanist beliefs, as of the metre and expression of the poetry itself—can think the country would collapse if he left it. But of course I cannot say anything like this so I’m silent, enjoying the green grass on the side of the road, and trees that would look suburban and pathetic if it were not for the life everything seems to hold when in his presence.

I think, too, that some of the hatred is personal in quite another way: the suicide of Sylvia Plath has turned the entire ‘tribe’ against her husband. Details of the other tragic deaths—of Assia Wevill and her child—have done little to improve his reputation. Something in Ted, however, believes himself indispensable to the nation. It’s all very odd indeed.

‘What are you writing?’ Ted asks. He has picked up some of my thoughts perhaps, on words and magic realism and on his own unflinching way of showing the reality of pain, in a painful world. Yet he hasn’t read my thoughts on the disasters of the women he loved, I believe—for the car swerves angrily as I give my answer.

‘I’m… I’m trying to find out about Sylvia,’ I blurt out. ‘Who is Sylvia, What is She?’ I go on, hardly able to understand this self-conscious and tactless nonsense coming from my lips. Of course I want to know about Sylvia, I long to add, and I want to know who she was. Why aren’t I allowed to bring her into any conversation? But all of that goes unsaid, and the car slows, nosing towards an exit, a side road to take us away from the West and back into London.

‘Don’t talk about Sylvia,’ Ted says.”