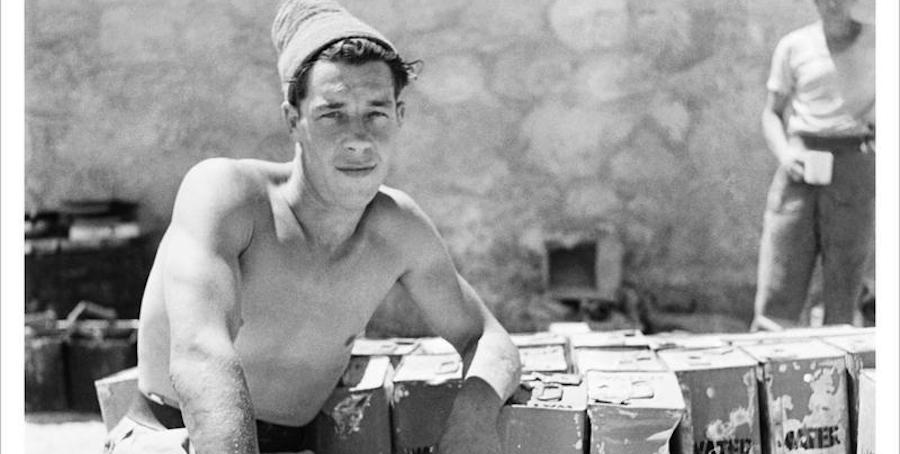

Cecil Beaton may be best known for his society portraits, but like Bill Brandt and Robert Capa, some of his most powerful photography was taken during the Second World War.

By Bella Bathurst

At the outbreak of war in 1939, the British establishment mistrusted photography almost as much as they mistrusted Nazis. “Snappers” were seen as vulgar and intrusive, and though the military benefits of the medium had already been proven during the First World War the armed services did their very best to avoid any connection with it. Their enemy had no such qualms: when war broke out, all professional German photographers were conscripted into a specialized unit known as the PK (Propaganda Kompanien) and instructed to “influence the course of the war by psychological control of the mood at home, abroad, at the Front and in enemy territory.” Those who did not – who failed to produce patriotic or compelling images, or who refused to shoot certain subjects – were reassigned to the Russian Front.

In Britain, it took until 1942 before Churchill’s great champion Brendan Bracken arrived at the Ministry of Information (MoI) and took control. Himself an entirely confected masterpiece made mostly from invention and elision, Bracken knew exactly what the value of propaganda could be. Almost immediately he brought all Britain’s photographic efforts under partial or complete Ministry control and split the work of professional photographers into four separate press units – one for each branch of the armed services, one for aerial surveillance, one for the press corps, and one for a small group of stars.

Starriest of all was, of course, Cecil Beaton, a polymath with an eye hungry for both visual and social magnificence. He got it: at school, he was vigorously bullied by the equally socially ambitious Evelyn Waugh. By the mid 30s Beaton was working almost full-time for Vogue and was already famous for the languid enchantment of his style. He took the MoI job not because he was short of work but because he was restless and wanted to contribute to the war effort. Even so, he seemed a curious choice as a battlefield photographer. Left to his own devices, he might well have taken a war populated only by himself and the occasional duke. Instead, the MoI sent him to a shipyard and a munitions factory. “This war, as far as I can see, is something specifically designed to show up my inadequacy in every possible capacity,” he grumbled at the time.

Beaton and the MoI eventually reached a queasy truce. The Ministry wanted obedient images taken to order; Beaton wanted an adventure. Sent off to photograph the battlefront in West Africa or Sierra Leone or the 8th Army in the Egyptian Desert, Beaton loved the challenge of reportage but initially found it almost impossible not to put the composition of an image before the subject matter. But by March 1941, when sent to photograph the RAF, he had begun to enter into the swing of things. “The fact that there were people of character living under dramatic conditions inspired me to adopt a more realistic approach, and the freedom of doing a straightforward piece of reportage was something that I found stimulating. My equipment consisted of one Rolleiflex and a flashbulb, so my powers of ingenuity were given full rein.” His output was prodigious. In 1974, the Imperial War Museum organised an exhibition of some of the 7,000 photographs he’d taken for the MoI. “It was fascinating to see the scenes in old imperial Simla,” he wrote afterwards, “the rickshaws drawn by uniformed servants, the grandeur of the houses, the men on leave swigging beer, and to wonder how I had been able to “frat” with such unfamiliar types … The sheer amount of work I had done confounded me.”

By comparison, Beaton’s contemporary Bill Brandt had spent the 1920s documenting the social consequences of the Depression in London and the north. During the war, he worked simultaneously for both the MoI and Picture Post photographing life on the Home Front, including the Blitz and the London Underground bomb shelters. Brandt, “had a mouth as loud as a moth and the gentlest manner to be found outside a nunnery,” according to the Post’s editor, Tom Hopkinson. He watched with an outsider’s eye, and he often seems as much obsessed with the slip of light on brickwork as he does with the shine of a miner’s eyes. Sometimes, his images look like pictures taken by an architect. There’s no sense of motion or of a moment frozen – as Brandt said himself, “the things I am after are not in a hurry.” His images of London during the blackout sum up his work. He took the pictures by moonlight sometimes using half-hour exposures and often ran the risk of being arrested himself. The London they show is intact but empty, coldly beautiful, populated mostly by ironwork and trees. It’s not a ruined, post-apocalyptic cityscape – it’s full of the same buildings which had stood there for decades or centuries. It’s just got no people in it.

Best-known of all wartime press photographers is probably Robert Capa who shot ten films at Omaha Beach under fire, got them back to London and gave them to the printers at the Life darkroom. In his haste to meet the New York deadline the lab technician overheated the films, destroying all but eleven of the frames. Less well-known is the work of Marty Lederhandler, an American photographer who was also there on the beaches of Normandy. To get his films back to Associated Press’ London office for processing he had been given two racing pigeons, each with canisters attached to their legs. Having shot what he could, Lederhandler put the films in the canisters and sent the pigeons off into the sky. Three weeks later, still in France, he came across a German newspaper. On the front page was one of his pictures. The pigeons had flown in the wrong direction and into enemy hands. The Germans had printed them, and given him full credit.

Many of the best-known and most recognizable British images of the war were taken on German cameras with German lenses and German film by Jewish German photographers

Many press photographers were conscripted into the various service media units. Bert Hardy, who by 1942 had already made his name at the Post, was assigned to the Army Film & Photographic Unit. Aside from talent and an unquenchable interest in people, Hardy’s great knack was just being there. Somehow he managed to be present at every critical turning point of the war from the London Blitz to the D-Day Landings and the first Allied troops going into Belsen. He was charming and classless, he had a genius for making the best out of difficult conditions and he was prepared to try almost anything in the pursuit of a good image. The AFPU sent their photographers all over the place: Africa, the Middle East, the Western Front, El Alamein, Operation Market Garden, the Liberation of Europe. Several were killed on assignment. When two of Hardy’s colleagues died, “it didn’t seem to affect me at the time, but the next day when I was eating I began to shake so uncontrollably that the fork dropped from my hand.”

Lee Miller was another war photographer with a connection to both the Post (through her husband Roland Penrose) and to Vogue. Miller had started out as a model in New York but retrained in photography, moved to Europe, met Penrose and in 1942 was taken on by British Vogue as their official war correspondent. In 1938, Penrose was recruited to teach camouflage techniques at the Osterley Park battle school. One of his better-known teaching aids was a photograph of Miller, naked except for some khaki-coloured paint, a bit of netting and a handful of shrubbery. Shortly beforehand, Penrose had been given some dull matt olive-green paste by a cosmetics firm and asked to test its effectiveness for camouflage. “Thinking that the experiment should be done thoroughly, I went with Lee one hot Sunday afternoon to a large secluded garden in Highgate belonging to our friends Peter and Gertrude Gorer. Lee, as a willing volunteer, stripped and covered herself with the paste. My theory was that if it could cover such eye-catching attractions as hers from the invading Hun, smaller and less seductive areas of skin would stand an even better chance of becoming invisible.” He had a point; his camouflage manual later became the standard-issue British army text throughout the war.

The last group of photographers were perhaps the bravest. These were the surveillance pilots, the men of the Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (PRU) who took photographs within enemy territory. In order to keep their planes as light, quick and undetectable as possible, the PRU requisitioned several Spitfires and removed their guns, reasoning that their pilots’ best defence from enemy fighters was to flit beyond reach of fire. To take detailed photographs of the ground far below, the cameras needed huge – and very heavy – lenses. Once the cameras and the fuel were in, there was neither space nor strength for either navigator or weapons. Asked if they minded being unarmed, one PRU responded, “Oh no! Never! Don’t you understand? That’s the whole thing about photographic reconnaissance. It’s the only sort of front line job in this war where you aren’t asked to kill.”

The buildup to war during the 1930s had caught the RAF unprepared and it had taken the efforts of one man, an Australian named Sidney Cotton, to haul aerial photography into the intelligence frontline. In the months before war broke out, Cotton used his twin-engined Lockheed to fly over Germany and photograph the landscape below. It took him a while to get the formula right; at 20,000 ft, the cameras frosted up and the film stock shattered. Cotton figured out a way of directing the warm air from inside the plane to the cameras which allowed reliable photography at high altitude, but meant that the pilot froze. In June 1939, Cotton flew to an air rally at Frankfurt where his Lockheed was widely admired by several senior Luftwaffe officers. Cotton offered to take them up for joyrides, and so, accompanied by much of the Luftwaffe High Command, he flew over much of the Rhone valley, chatting away while quietly photographing the German preparations for war as he went.

The combination of recklessness and reasoned quietude is probably best expressed by the best-known of all the surveillance pilots – the French writer Antoine de Saint Exupéry. Flight to Arras, his account of a near-suicidal reconnaissance mission, was distilled from months of experience flying intelligence-gathering missions. Saint-Ex was happiest in the air, reckless with his own life but devoted to his crews. Three times, his friends tried to get him moved to safer duties; three times Saint-Ex evaded them and returned to flying. “Everything about him was bizarre,” wrote his air-force room-mate, “his name of a knight of the Holy Grail, his face, his body, his bearing – both heavy and ill-at-ease on this planet, the impression he gave of being a hunted man; even at times of having lost all sense of reality, as for instance, when he looked for his bedroom door on the wrong wall.” The British regarded him as a complete liability; “a problematical French celebrity who insisted on flying Lightnings when he was much too old and absent-minded.” But the courage of Saint-Ex and his extraordinary Allied compatriots (including Adrian Warburton, once described as the most valuable pilot in the RAF) resided not simply in their physical bravery, but in their compulsion to get the images at almost any cost. Warburton once flew repeatedly at over the Maltese naval base at Taranto at an altitude so low that Italian gunners were unable to fix their sights on him. His navigator was able to read off the names of the battleships in the bay without binoculars, and when the two returned to base, part of a ship’s radio aerial was found lodged in the tailfin of his Maryland.

Having shot what he could, Lederhandler put the films in the canisters and sent the pigeons off into the sky. Three weeks later, still in France, he came across a German newspaper. On the front page was one of his pictures. The pigeons had flown in the wrong direction and into enemy hands. The Germans had printed them, and given him full credit.

Those films which did make it back to Britain were handed over to the Photographic Interpretation Unit for processing, measurement and interpretation. The interpreters, who included Michael Spender (brother of the poet Stephen), and the actor Dirk Bogarde, were trained first to recognise normality, and then to understand difference. “Nothing happens,” they learned, “without leaving a trace.” Sidney Cotton recruited several women from the WAAF since he believed they were already endowed with all the qualifications necessary for the work. “My reasoning was that looking through magnifying glasses at minute objects in a photograph required the patience of Job and the skill of a good darner of socks,” he said. They learned to calculate the height of a building from the length of its shadow or the speed of a ship by the ripples left in its wake, tell the difference between battleships or fighter plane from their silhouettes, and recognise the disturbance across a patch of nondescript French farmland from one month to the next. They knew about Dunkirk in advance because of freshly ploughed land at Cap Gris Nez and by comparing successive images of German camouflage around their shipyards, were able to predict exactly when new U-boats were to be launched. Perhaps their greatest achievement was to find the German V2 rocket program at Peenemunde. The site was bombed by the Allies just as fresh concrete had been laid, and the German V2 rocket programme was delayed by six months or more.

By 1945, photography had proved itself more valuable to the war effort than anyone – even the snappers themselves – could ever have supposed possible. Even so, it is worth noting two curious postscripts. The first is the mechanics of it all. Many of the best-known and most recognisable British images of the war were taken on German cameras with German lenses and German film by Jewish German photographers before being printed up onto German paper stock by German Jewish printers who had arrived as emigres to London to escape persecution by the Germans. Throughout the war, there was a thriving black market for German materials: then as now, the Germans make the best.

Perhaps even more ironically, many of the images taken on less high-quality stock are beginning to vanish. Because of rationing and shortages of raw materials, much of the film used by Hardy, Beaton and the photographer pilots is degenerating. Sub-standard gelatin used in photographic emulsions results in something called “vinegar syndrome,” and ultimately to the negatives themselves falling apart. Rationing lasted well into the 1950s, and almost twenty years of film is affected. Many museums and picture libraries are struggling with the problem; restoration is feasible only for the most famous images and it may not be possible to digitize everything else fast enough. The rest – the thousands of pictures and miles of footage collected at such huge cost – may soon be gone.

Bella Bathurst is the author of The Lighthouse Stevensons, Special, The Wreckers: A Story of Killing Seas, False Lights and Plundered Ships, and—most recently—Sound: A Story of Hearing Lost and Found.