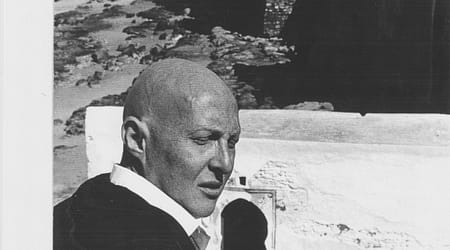

The artist Jorge Colombo directs his gaze at Narrowsburg, his home town – and ours.

When I opened One Grand Books in Narrowsburg in the fall of 2015, Jorge Colombo was among those local figures who emerges at the periphery of your field of vision. I’d see him at town social events – a street festival, an art opening, at a gathering at our wonderfully eclectic art complex, Mildred’s Lane (I’ve written about that here) – and then suddenly it seemed he was just about everywhere at once. Whatever the weather you would see him outside, asking someone – a friend, a stranger, it didn’t matter – to hold a particular pose while he pulled out his iPhone and took their photo. Most of these images would up on his Instagram feed which operated as a virtual flipbook of an entire community, not unlike the way Christopher Makos recorded the expansive community around Warhol and The Factory. It was always something of a thrill to find yourself in his feed. Of course, I knew early on that he was also an illustrator of some renown, best known for his New Yorker covers like this one, and was flattered when he began accepting invites to events I was hosting – sometimes at the bookstore, often at Neuehouse, a co-working space in Manhattan where I managed some literary programming for a while. I’d see him in the audience memorializing, say, Laurie Anderson in conversation with Julian Schnabel on his iPad, his preferred canvas. It so happened that Jorge and his wife, the artist Amy Yoes, were in the process of converting an old barn into their home, and while they were waiting to complete the work Jorge sometimes stayed with me. It was in my living room one evening that we had the conversation below. Of course, when Grand Journal launched last fall, Jorge was the obvious person to invite to create one of our covers, but it quickly became apparent that images from his long (endless?) journeys around Narrowsburg would make a fitting portfolio for the issue, a declaration of the journal’s roots in this small, dynamic, endlessly surprising community.

Grand: Jorge, it’s a rare day to catch you not in the midst of creating an image. Were you as visually-stimulated in your childhood?

Jorge Colombo: I was fascinated by images, by narratives, by comic books, but nobody in my family was particularly visually inclined. I grew up in a small town just outside Lisbon, and there was a general conservativeness on the Portuguese fabric that only began to change in the 1980s. There used to be a club in Bairro Alto, the center of Lisbon, called Fragil, founded by a guy called Manuel Reis. A lot of people of my generation congregated there – nothing more than dancing and drinking but somehow it seemed to be the axis of a lot of other things: music, new galleries, new publications, new people. Reis was a great defining character and the scene he created showed us that we were not alone, that other people were on our wavelength, that we had a certain sense of power and agency and reach, and that we had an audience that was ready for us. That was my happy ’80s.

But you chose not to stay in Portugal but to move to the U.S.

I had a lot of enthusiasm, devotion, and seriousness about what I was doing, but I didn’t have any training, I dropped out of school because I did not trust the teachers – in fact, I hated most of them. I had that youthful arrogance of thinking they were not good artists so I could not possibly take them seriously. I wanted something that felt superficially cool, superficially European, American, international. For my generation, at least initially, there was nothing exciting in the idea of something intrinsically Portuguese. On the other hand the people of my generation who went furthest were precisely those who embraced the Portuguese heritage in the most unabashed way. That was not the case for me. I spent six years of my professional life in Lisbon and then I got out, after meeting my wife [the artist Amy Yoes] and following her to Chicago.

What were your first impressions of America?

Your first impressions tend to be very precise, very self-assured, and very wrong. It’s very easy to think you know everything about a country in the space of getting out of an airport and riding in a couple of taxi cabs. It’s only after living a few years, or tens of years, in a country, that you realize it’s more fluid than that. I landed in the US during Bush 41, and was soon driving with Amy across the country, so we ended up in places like Montana, or Arkansas, before I was familiar with New York. Of those years the thing that makes me most nostalgic is the large format Rand McNally Road Atlases. There was something absolutely miraculous about the way that levels of information seemed invisible until the moment you needed to know about them. They were heavenly in the pre-GPS world, to say nothing of the fact that you could also always also look at what you were missing, because you were forced to look at a map and see not only where you wanted to go, but where you could be going, if only you made a small detour. If we realized we were close to the gravestone of Hank Williams, well, why not?

When did you start working at The New Yorker?

I did my first drawing for the inside pages in 1994; it felt incredible – it’s an epic moment to be published in the The New Yorker. Françoise Mouly is an amazing, sophisticated editor. Like any good editor she pushes her artists into accomplishing the best of themselves without making them into somebody else, because if she needs somebody else she knows who to call. There was some interesting advice that Françoise gave me which was: Do not be afraid of the obvious. Remember that there are a lot of things for a New Yorker that can come off as touristy or obvious, but for a lot of other people they are still new or still exciting, and we are not doing this for the jaded insider – we are creating images that somehow correspond to a fantasy, or bring a revelation to somebody that is not entirely familiar with the context. This comes back to the notion of trying to remain a tourist inside your own town for all of one’s life.

How would you describe your aesthetic?

If you don’t have a working thesis in your mind, a point that you want to prove in your work, it’s just really random images. What I felt about a lot of the urban landscape of the US, was that it was an interesting mix between the developing world and the industrial revolution and the future. There were things that were falling down, patched-together that felt – like the New York subway – prehistoric, but mixed in with things that were innovative and of the future.

I started equating my passion for the dilapidated parts of the urban landscape with the way people themselves are. My favorite kind of architecture is the architecture that happens in spite of architects – where something is built, and something is built wrong, and something is added and something breaks down, and the function changes, and that’s what happens in our lives – we are all a collection of good and bad influences from parents and teachers and friends and society, and we are playing a part that we were not necessarily designed for. Landscape and people alike.

How did you gravitate to drawing on an iPhone?

Originally, I worked in pen and ink; I would sketch somebody, then go home and spend an hour doing a postcard size drawing in pen and ink and watercolor. But even in my drawing I was trying to do things that were a little different – sketches with a looser line, or going to clubs and drawing people bumping into each other. I wanted to be on location but I wanted quick gratification – I know my limits – and I wanted to be working on location, and if possible to finish the picture at the same time. So I got an iPhone. At the beginning I felt as if I was drawing with my elbow, and then on a road trip to Vermont I realized that I could draw in the dark inside a car, and that sealed the deal. The style was completely different, since I couldn’t have that same precision, so I went for the painterly approach as opposed to the draftsman. The example I give is that it’s like a musician who plays the piano but then decides that he’d like to play inside a canoe, so a piano won’t cut it – he has to change to, say, a harmonica.

Did the iPhone liberate you?

I don’t have a particular fetishism for the materials of art; I remember with some fondness the textures and smells and the feel of the brush on the rough paper, but I can live without it. I always had a tendency to pair back my brushes – if I had 12, I’d think, maybe I can get away with six, so I liked the idea of having everything in the iPhone, and later the iPad. I don’t have the faintest interest in looking at my work on paper, because you can go further with the pixel. And I like the fact that I can work anywhere.

What prompted you to move from New York City to Narrowsburg?

I started feeling that if I never got to leave New York it would be fine, and that felt good. And then as time went by I started to realize that it was much more fun to be a beginner than a veteran – the sense of starting something new was more appealing than the sense of sticking to the same thing because it’s what you’ve been doing. Narrowsburg was not exactly not part of the plan. I thought it might be a different city, perhaps, but Amy and I had been frequenting Narrowsburg all these years, mostly to see Morgan and the Mildred’s Lane crowd that we’d been part of. So we left our New York City apartment, and this is our only address now.

Does being in a small town have a perceptible effect on the work you are creating.

I am the kind of person with no imagination. I can only draw things that I am looking at. In New York I have entirely different neighborhoods, a few blocks or a few train stations away. Here I have a very small number of streets to draw. That, to me, is a pleasant challenge, as in: How can I find the same incredible variety here that I could find elsewhere? I’m not entirely sure how, but I prefer to have that assignment than doing what I already know how to do.

What has surprised you about being here?

First of all I’m starting to get the impression, more and more, that it’s not just your average small town — it’s more distinctive than some other places, more unique. Something about it seems to make it more magnetic to people that want to push the town to realize its full potential. Maybe there is something ultimately human about being an actor in a play that has fewer characters rather than in a play with endless characters.

Finally, we’d love a recommendation of a book that has influenced and informed you?

The first that comes to mind is the Hitchcock/Truffaut interviews which taught me that no choice is an accident, and that everything is built with the purpose of creating an effect. Another is David Hockney by David Hockney which I bought in 1982, and a third is Orson Welles in conversation with Peter Bogdanovich.