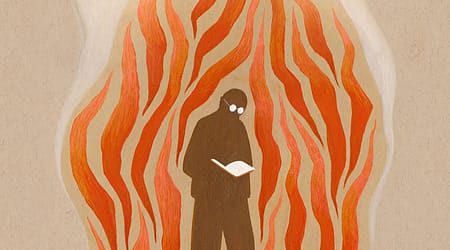

The French illustrator Iris de Moüy has a knack for finding the essence of things. Her lines, minimal and bold, often achieve what whole paragraphs of description cannot. “I’m inspired by simple forms, from the cave paintings of Lascaux to Henri Matisse drawings,” she says. “Simplicity is a complex thing to master. I try to have a clear idea of the impression I want to create, and then I produce many variations both intuitively and consciously. I remove rather than add. In the end, I pick one drawing.”

That discipline of subtraction—of paring away until only the essential remains—gives her images a certain vitality. Yet austerity is not the point. Her figures are tender without being sentimental, which is deliberate. “I just held a similar level of regard for children and women as people usually do for men,” she explains. “I hate being soppy. Spontaneity always makes me feel safe and comfortable.” It’s a refusal of clichés, a way of granting every subject the same clear-eyed attention.

Animals recur again and again—cats, horses, birds, foxes. “Animals have a strong symbolic power,” she says. “They can express a wide array of emotions. They are also fascinating to observe and draw.” In her hands, they are both characters and archetypes, stand-ins for human impulses too mercurial to catch directly.

Her other great influence is dance. De Moüy’s fascination with movement—Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Pina Bausch, Maya Deren—has shaped the elasticity of her line. “The body is a language on its own, so true and touching,” she says. “Observing the body and movement through live drawing has always been a part of my practice.” Her drawings often feel like the aftermath of motion.

Paris, inevitably, is the background hum. She once admitted that Colette helped her fall back in love with the city after leaving London post-Brexit. “I was thinking of one particular book: Colette’s Paris, Je t’aime!” she recalls. “Because Colette wasn’t born in Paris, she had to find her own space in the city. It’s all about choosing your life, freedom, and joy—observing with fresh eyes.” That perspective informs de Moüy’s depictions of Paris, which she has described elsewhere as “beautiful, vibrant, messy, a bit naughty and dirty.” Asked if she consciously incorporates these less-polished textures into her work, she shrugs it off: “It’s hard to say. I’m a Parisian. I guess all of that is in my genes!”

Her home life, too, has shifted her art. “I love to have teenagers around me,” she says of her children. “They’re challenging, funny, and clever. Stronger and smarter than I used to be at their age. And I tend to avoid nostalgia.” Instead of looking backward, she absorbs their sharpness and humor, sponge-like, into her practice.

De Moüy has worked across registers—children’s books, fashion collaborations, advertising campaigns, as well as her deeply personal drawings. “I value teamwork and the challenge of adjusting to a concert and demanding commercial work,” she says. “But I also need to express personal ideas that I can produce in my own way. The two parts are mutually beneficial and inseparable.”

Asked what questions she is wrestling with now, she keeps it simple and direct: “I just try to keep working and believe in what I do.” It’s a deceptively simple credo, not unlike her drawings—stripped of embellishment, and alive with clarity.