Carter published her best-known short story, “The Company of Wolves,” in Bananas, among many other contributions; her “fellow writer in Clapham” also found his way into the magazine, with a tight, vicious short story, “Dead as They Come,” in which a man falls in love with a mannequin. At times the Bananas office sounds like a literary railway station, with writers departing and arriving at all hours. In this simpler era, before publicists turned magazine parties into branding ops, Tennant would celebrate each issue with dinners at her home, where Harold Pinter, Heathcote Williams, and Ted Hughes would bump around in her basement kitchen. One evening Andy Warhol was there—“wasted, drained of life or interest in the proceedings.” And then there was Joseph Brodsky with “his hundredth cigarette clamped to his lips.”

“Somehow Roth has fitted a rubber mat, green with a swirly pattern, in this tight space, and I find myself—there is nowhere else to go—standing on it. ‘For my exercises,’ Roth says. A silence falls, and I leave, suddenly aware I don’t want to be here at all.”

From the burnt diaries by emma tennant

On another occasion, Philip Roth invited Tennant to his “minute flat” where he wrote when in London. If it all sounds faintly glamorous, Tennant is quick to remind us that it mostly is not. Her account of Roth’s apartment is withering:

There is hardly any space, between desk, armchair, and wall, to stand in; but somehow Roth has fitted a rubber mat, green with a swirly pattern, in this tight space, and I find myself—there is nowhere else to go—standing on it. ‘For my exercises,’ Roth says. A silence falls, and I leave, suddenly aware I don’t want to be here at all. Whatever the ‘exercises’ are, I definitely do not want to be a part of them.

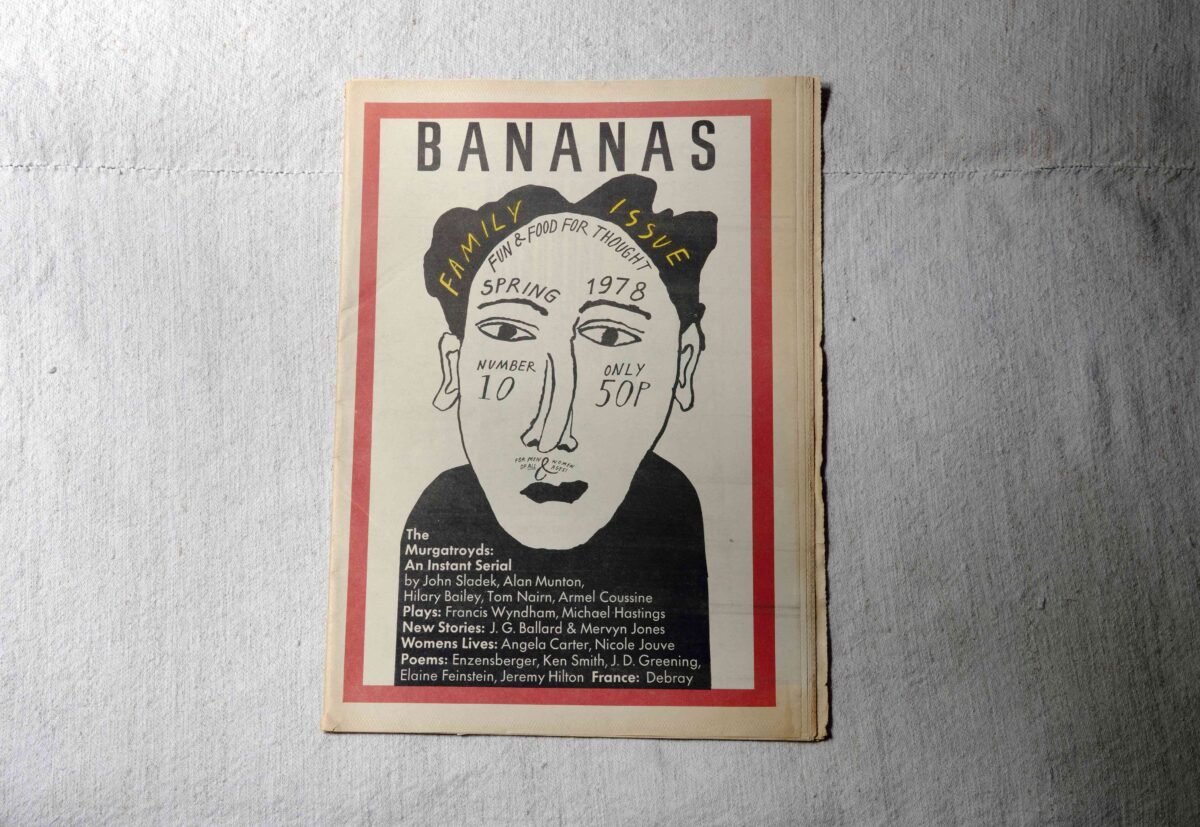

There were other literary journals in 1970s Britain, such as Ian Hamilton’s literary bruiser, The New Review, but nothing came close to the freshness of Bananas, with its scrappy energy and international outlook (there were early submissions from the Argentinian writer Julio Cortázar, whole issues dedicated to Russian and South American writing, and regular essays by the Scottish Marxist political theorist, Tom Nairn). Tenant writes of receiving Ballard’s manuscripts “with holes punched in them due to the violence of the writing,” a lovely analogy for the spiky, bare-fisted quality of her magazine.

The 1970s gets knocked for the sour scent of post-empire curdle, but it was also a decade of unusual equality, soon to be swept away by the Thatcher-Reagan revolution of the 1980s, a time when the gap between rich and poor was at its smallest. It was a moment when a genuinely subversive culture seemed to bubble up from the ground. It was a decade that closed out with punk.

Tennant edited 11 issues of Bananas from 1974 to 1978, when she sold the magazine to a young woman of means. The party to celebrate her final issue seems grim with foreboding. “I hear it was a bad party,” a friend tells her, and she agrees. “Yes, it was a bad party; I didn’t know half the people there. A Bananas party had just become something to crash.”

That, in a nutshell, was the difference between the literary culture of the ’70s and what was coming—a party that had become “something to crash,” the brash, over-glamorized ’80s and beyond, when art and literature would be commodified to death, and parties would have sponsors and a step-and-repeat, and guests that likely didn’t know what they were there to celebrate. Tennant, with admirable lack of sentimentality, notes that her magazine, would not be repeated “or probably even remembered.”

She was right on the first score.