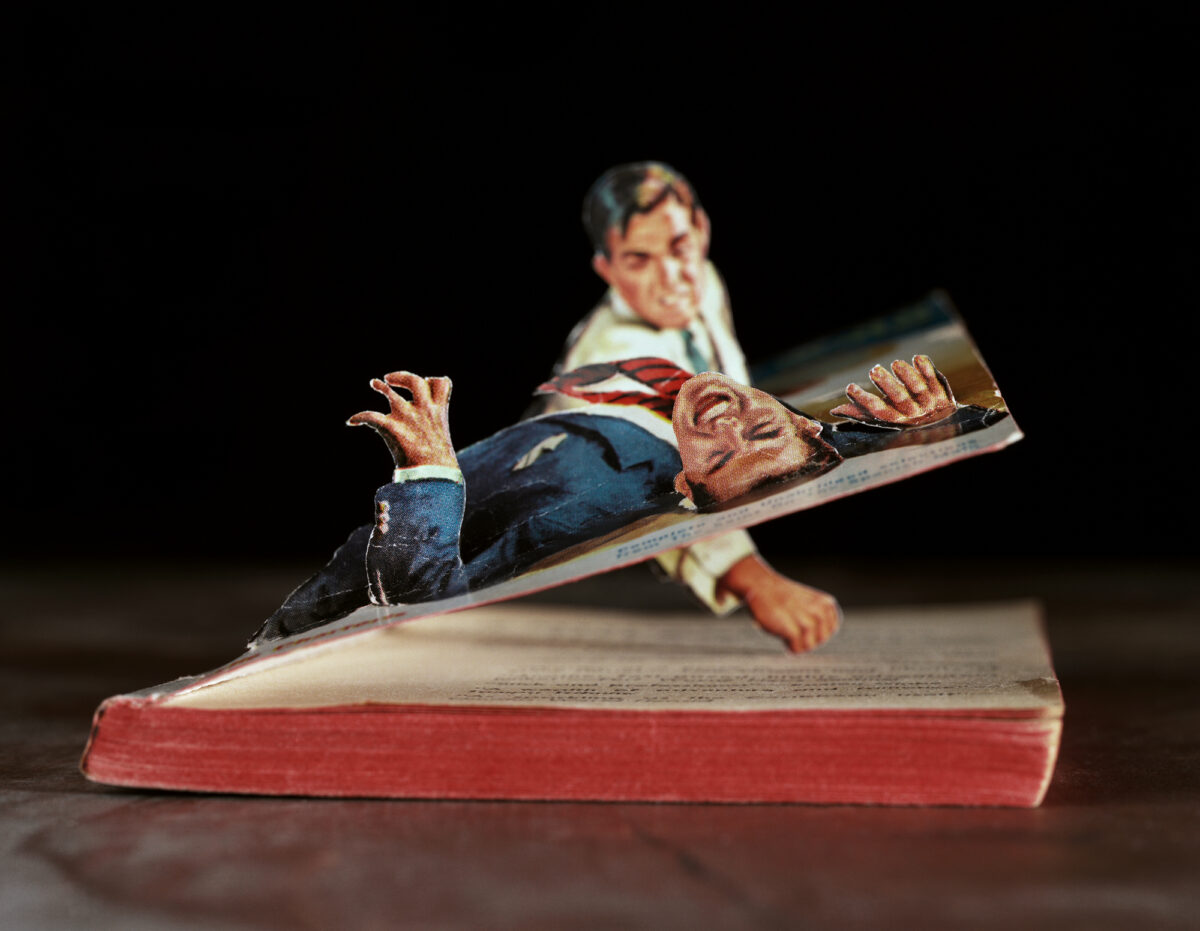

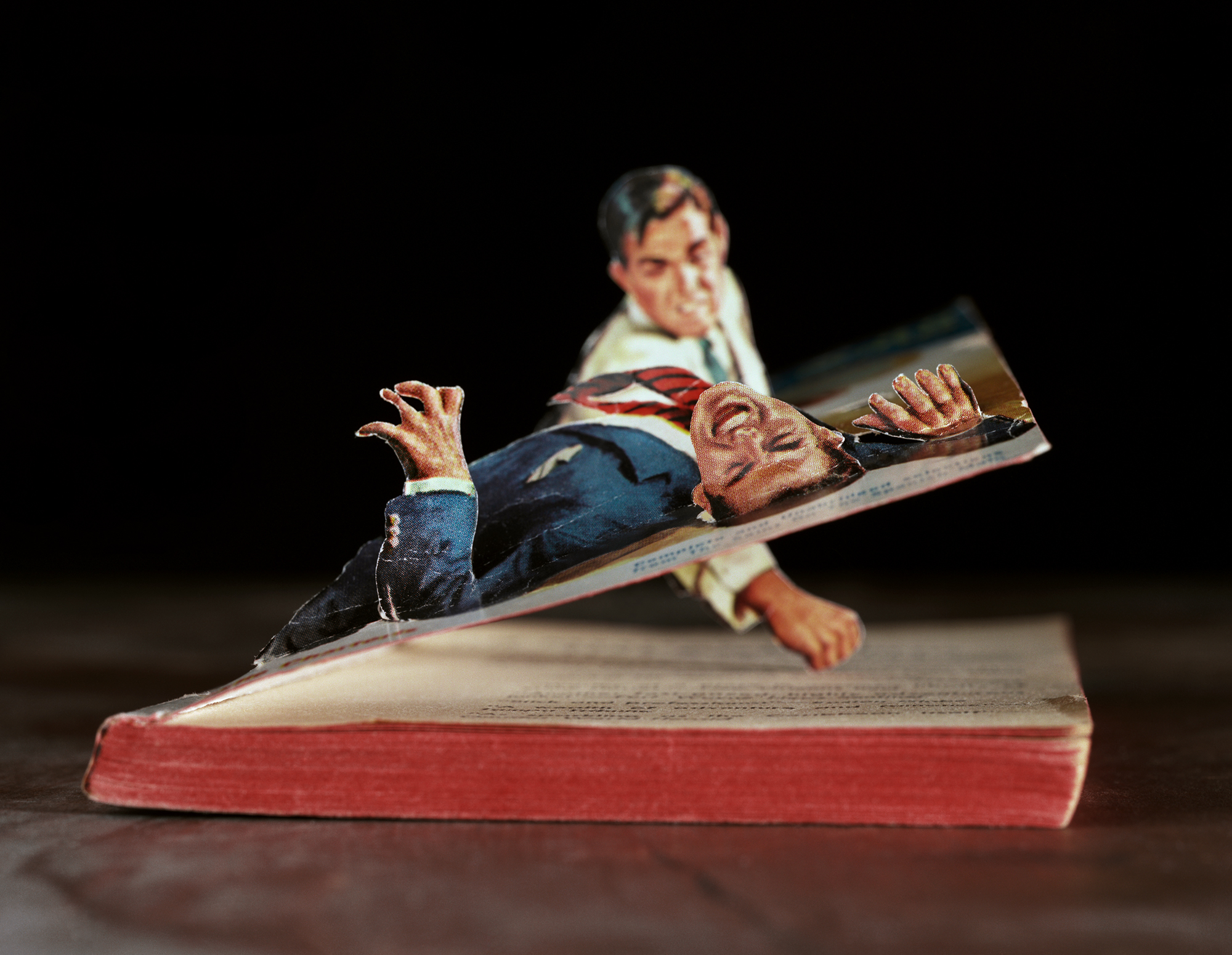

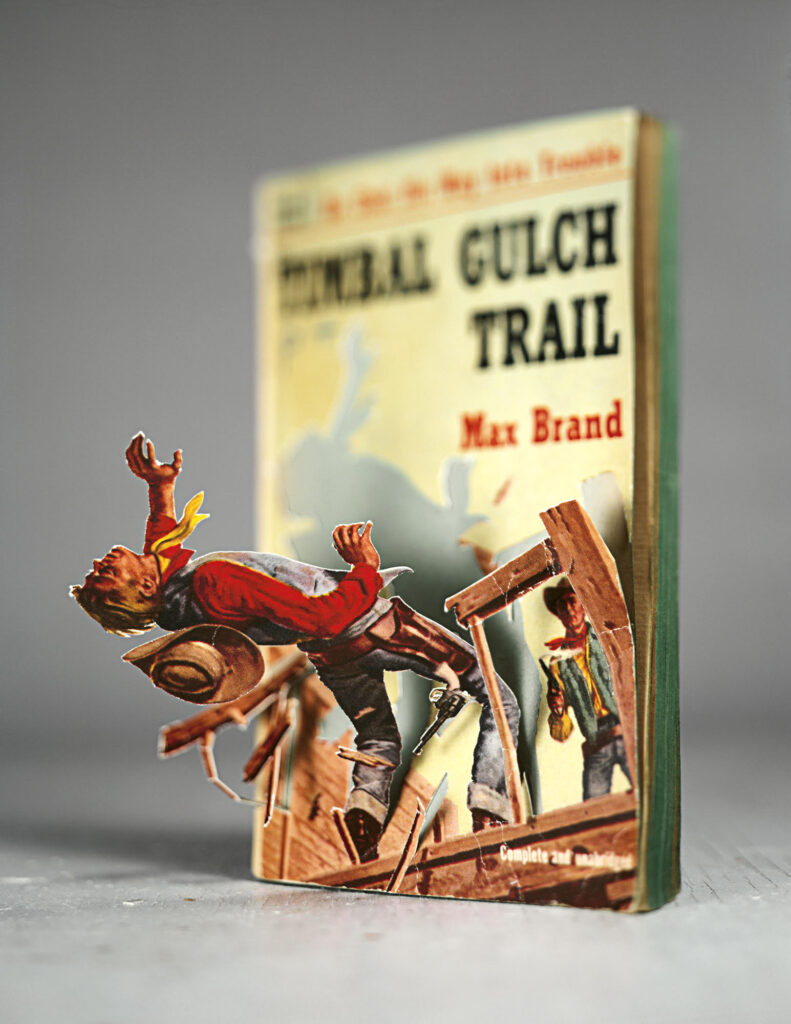

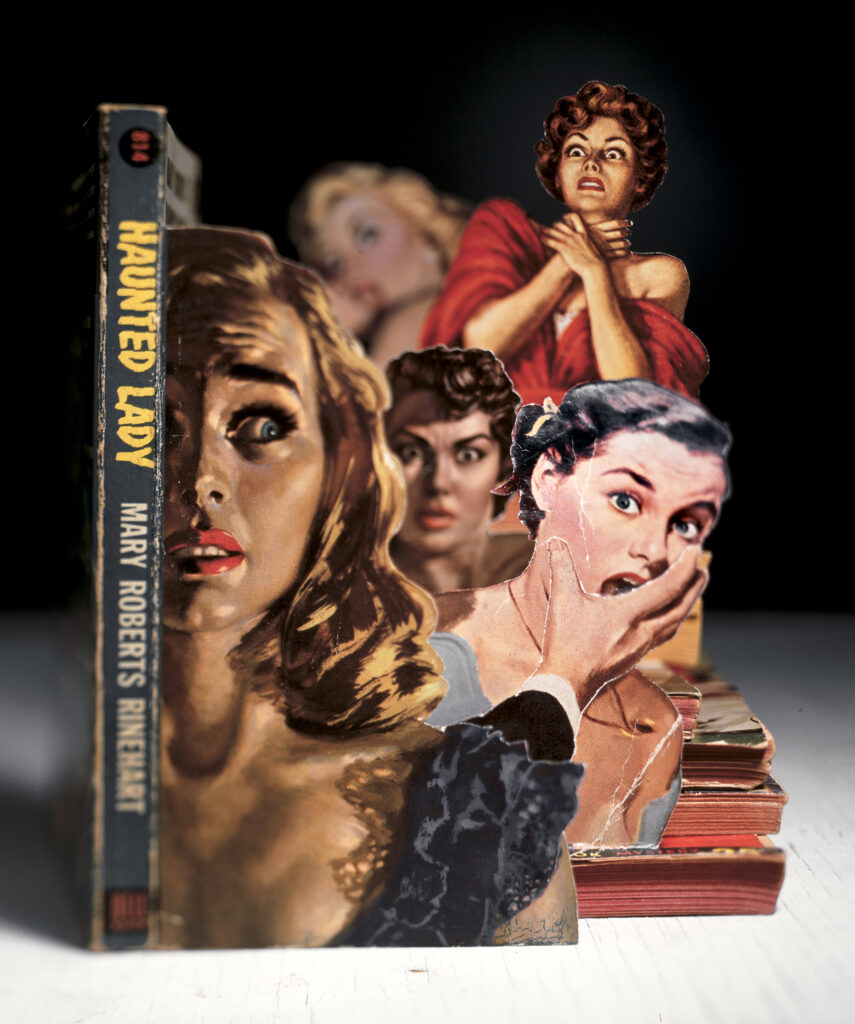

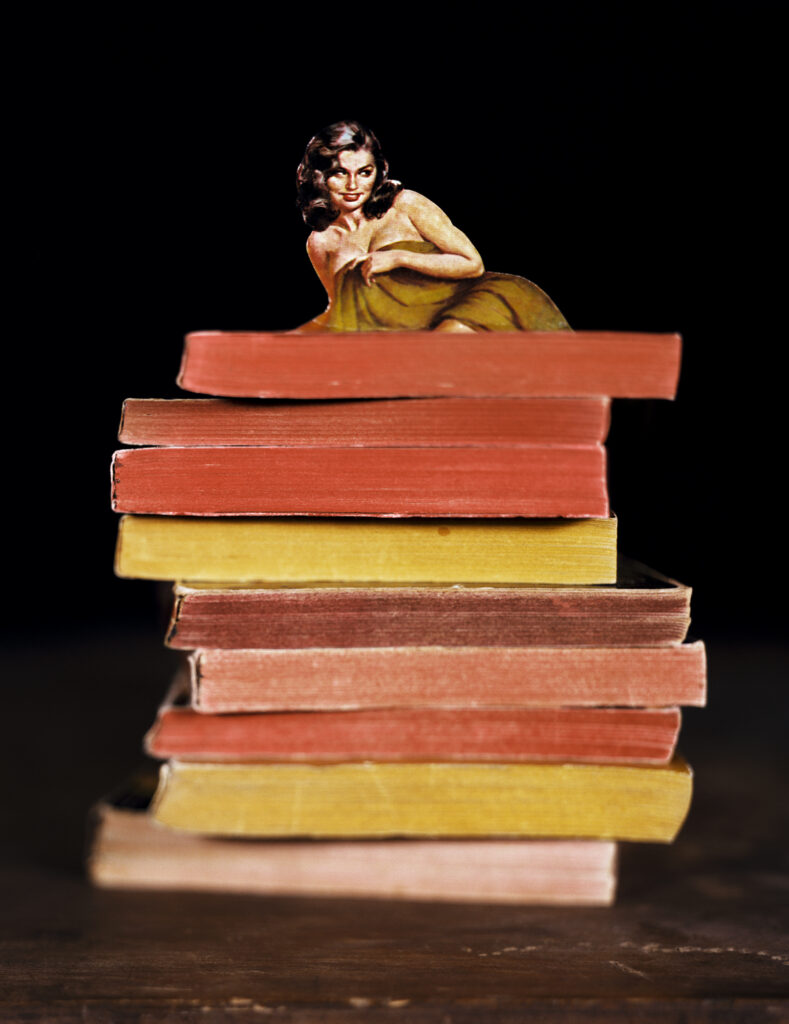

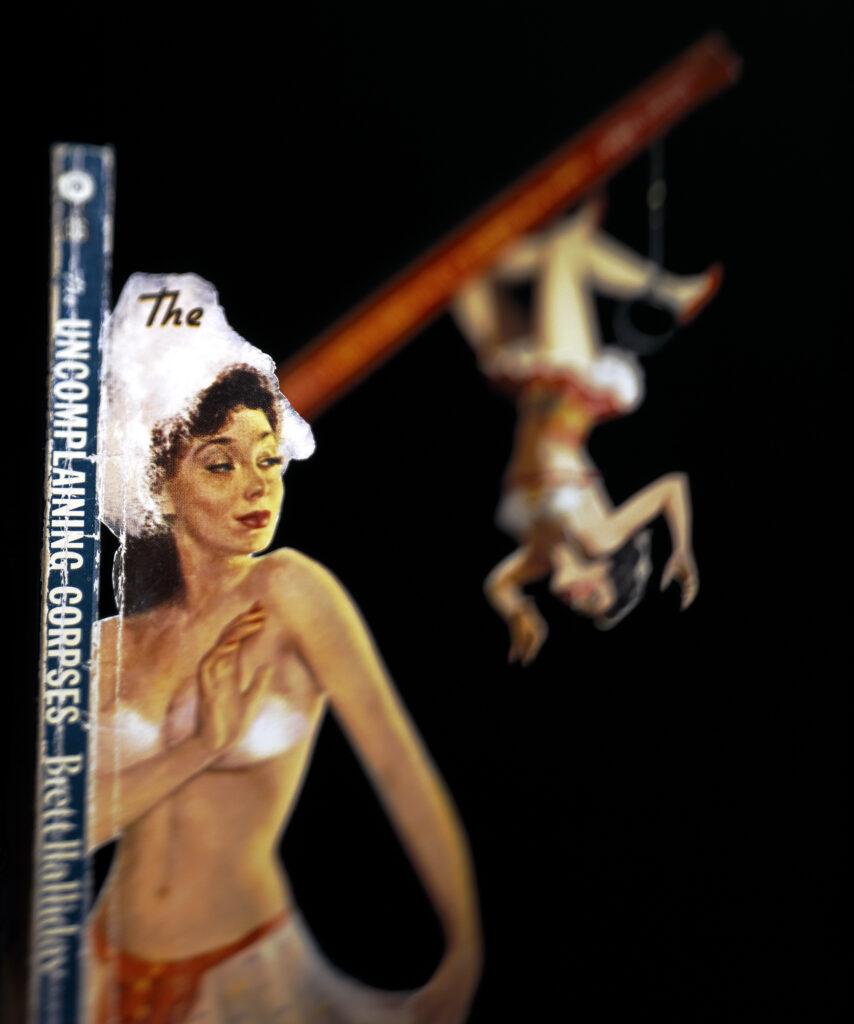

In Woody Allen’s 1985 movie, The Purple Rose of Cairo, a character steps out of the silver screen-era movie in which he’s appearing, and enters the real world. The line between art and real life is blurred. Fantasy has invaded real life. Something similar is afoot in Thomas Allen’s series, Pulp Fiction, currently on show as part of an online exhibition organized by the Joseph Bellows gallery in La Jolla, California. In each image Allen has reframed the lurid illustrations of tough guys and femme fatales from 40s and 50s pulp fiction by cutting and juxtaposing figures from the covers of dime novels. In “Knockout,” for example, a boxer appears to have tumbled off the cover of Frank O’Rourke’s The Last Round. Out of focus, in the far distance a woman throws her arms in the air like a triumphant victor (in the original the victor is a man). In “Timber,” a cowboy falls backwards through a fence and off the cover of Max Brand’s 1934 western, Timbal Gulch Trail.

For each of his photos, Allen creates something akin to a pop-up, using an X-Acto knife to liberate figures from their original two-dimensional background. In an era of AI-generated images and photoshop the sense of texture and depth and human intervention feel quietly subversive. And because it is figurative and graphic, and often very funny, Allen’s work is a natural fit for art directors at magazines and publishing houses. After seeing his work at an art fair in New York, the legendary book designer Chip Kidd invited Allen to create covers for reissues of classic crime novels by James Ellroy. Commissions came thick and fast for Harper’s Magazine, The New Yorker, New York magazine, Vanity Fair, The Virginia Quarterly Review, and Out, where I first encountered his work during my time there as editor. I was smitten. Allen’s work takes the familiar and twists it into something fresh. It also serves as an encomium to the skilled artists who created the original covers, widely dismissed in their time. “They’re so realistic and sometimes the expressions are so exaggerated that the storytelling in the faces alone was what really drew me,” says Allen.

If things had gone differently, Thomas Allen might have been a criminal justice lawyer. Luckily for us he hated studying law and turned to art instead, encouraged by a mother who took note of his childhood passion for creating dioramas on his bedroom dresser. Another spur to the young artist’s imagination? His train set. “I would make tunnels with books and lie on the floor and watch the train come around the tracks,” he recalls. “It’s just all these imagined realities.” Train sets, Santa Claus grottoes at department stores, the miniature interiors of Narcissa Niblack Thorne at the Institute of Art Chicago – all were grist to the mill of Allen’s imagination

At college in Detroit, Allen initially began working with pen and ink drawings of everyday objects like electrical plugs, but a photo class changed everything. Inspired by photo artists such as David Levinthal, Olivia Parker and Duane Michals, Allen began making collages with torn-up kids books and then photographing them. “For me it’s always been the making of the thing that was more important than actually taking the photograph,” he says. “People are, like, ‘Are these digital?’ And I tell them they’re not digital at all. They are all straight photographs, shot on large format film.”

Allen honed his practice on a fellowship with the McKnight Foundation, drawing mostly on science and anatomy books before turning to pulp fiction. “It kind of happened by accident,” he says. “I was cutting a book with two men on the cover one day and I pulled on it, and realized it looked like pop-up books, and that if you looked at it from one perspective, just by certain cuts and folds I could make, I could recreate an illusion of a 3-D space.”

Add an impish sense of humor – inherited, he says from his grandmother – and you get pieces like “Distraction,” in which a square-jawed 1950s archetype of masculinity checks out a shirtless guy behind him. It’s an alternate version of postwar America in which Rock Hudson didn’t have to live in the closet.

“One time someone asked if I had ever thought about altering and photographing gay pulp novels, but the painting style is totally different, almost cartoon-like,” explains Allen. “I thought the real trick was to take blatantly heterosexual novel covers, cut them, and pair them with others to transform them into homoerotic imagery. That’s how I started pairing more than one book together.”

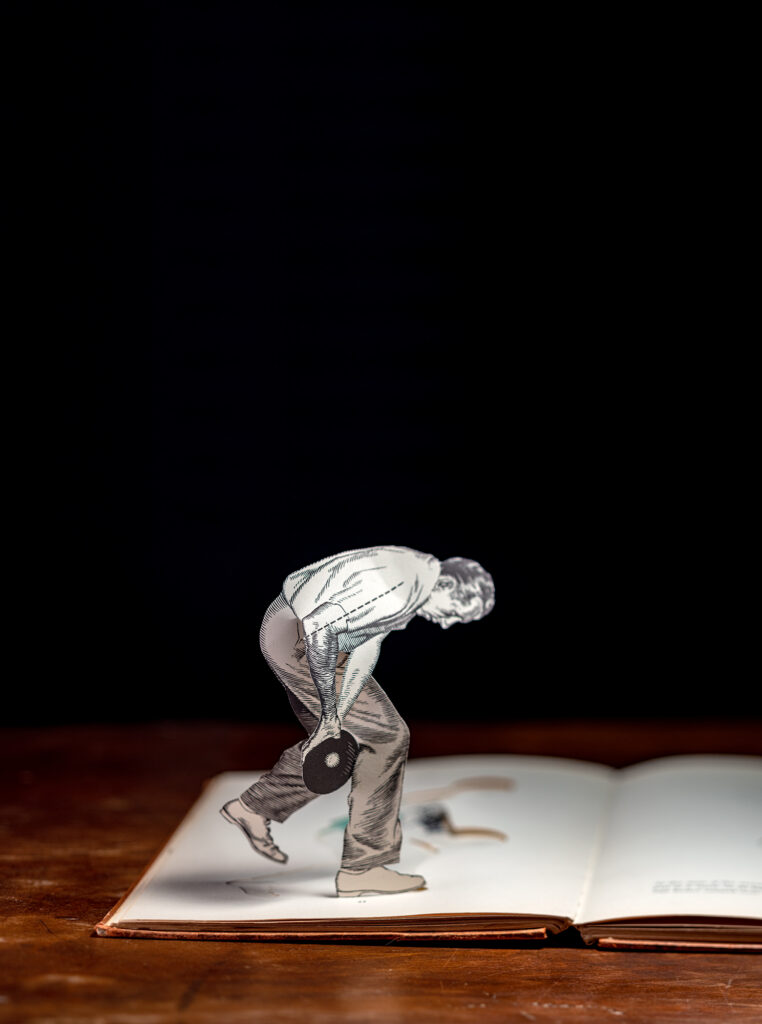

Today Allen is working on a new project, one more profoundly personal. When his mother died in December 2021, Allen found himself paralyzed creatively. “I feel like I grieved in the years leading up to her last day and convinced myself I would be ready when the time came,” he says. “I was not. The entire family was there and I was the only one who didn’t cry. I still haven’t.”

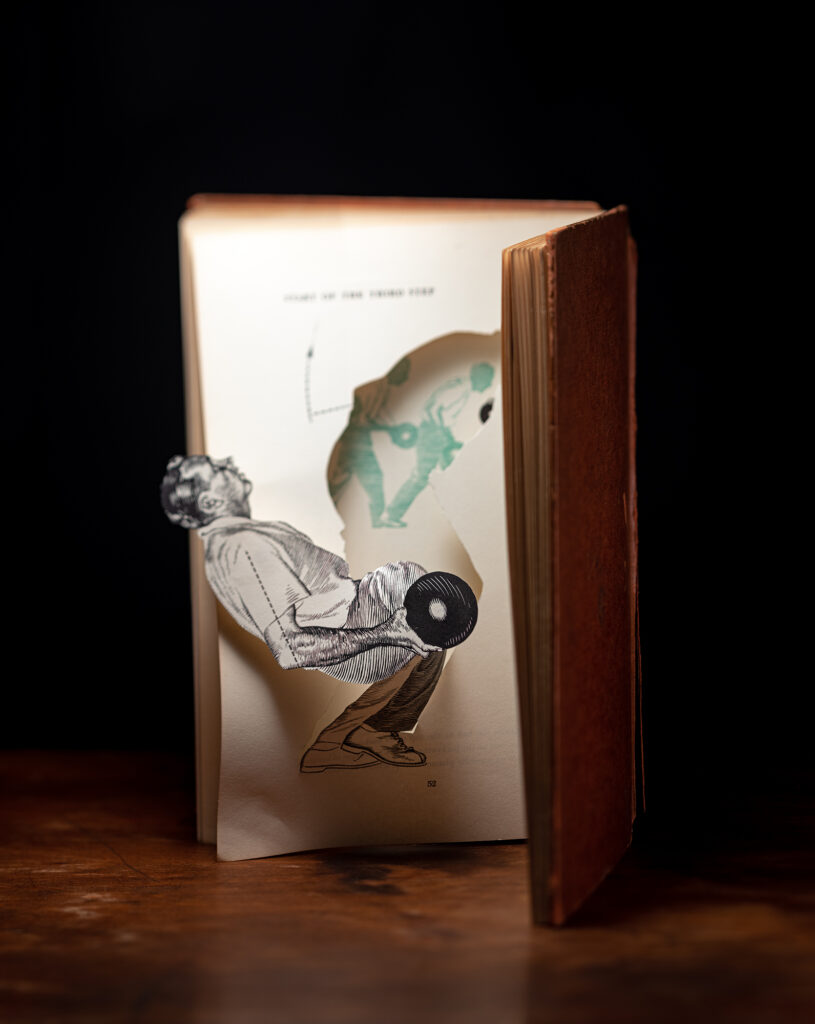

Then Allen found a 1958 paperback, 10 Secrets of Bowling, at a local antique mall, and something shifted. Looking at a drawing of a man bending over to pick up a bowling ball, Allen was immediately struck by the symbolism: “That’s what grief feels like,” he said to himself. Using delicate cuts and folds Allen reshaped the figures in the book to accentuate the challenge of holding the ball. After photographing the reworked pages, Allen uses photoshop to make composites from 35 to 40 overlapping exposures. In this way he is reworking the book from cover-to-cover, a first for Allen, and the most important project he has made – a tribute to his greatest cheerleader (and critic), and a meditation on the nature of grief. “It’s like carrying around an awkward and invisible weight that you have to figure out how to live with, because you can never let it go,” he says.

Pulp Fiction is now showing online at Joseph Bellows Gallery.